Obscure German Holocaust Archive Has Trove of ‘Lists’ of Jewish Victims of Nazis

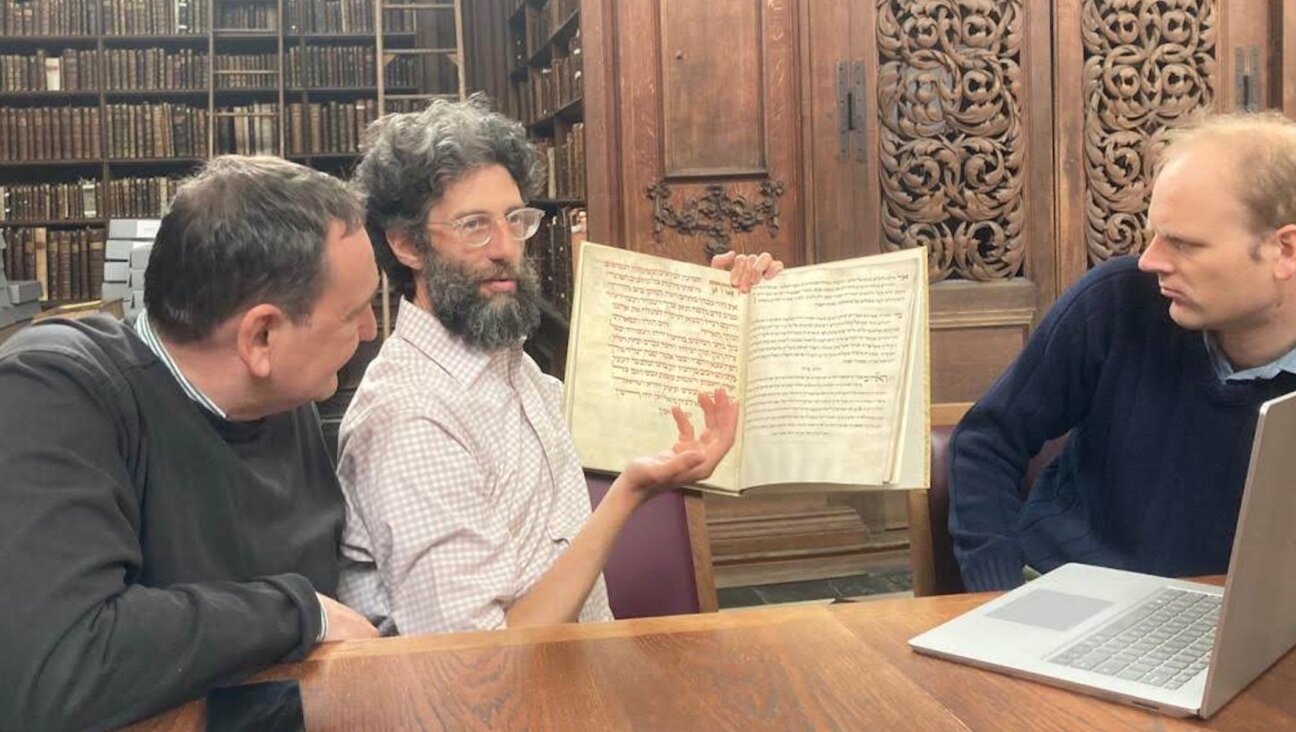

Trove of Information: The new managers of an obscure Holocaust archive in Germany want to expand outreach so victims can gain access to the trove of information about millions of victims. Image by getty images

George Jaunzemis was three and a half years old when, in the chaotic weeks at the end of World War Two, he was separated from his mother as she fled with him from Germany to Belgium.

He grew up in New Zealand with no memory of his early years, unaware the Latvian woman who had emigrated with him was not his real mother.

Then in 2010, a letter from the International Tracing Service (ITS) in Bad Arolsen changed his life. He discovered his real name was Peter Thomas and that he had a nephew and cousins in Germany.

“I was astonished, thrilled. After all this time, I was an uncle,” Jaunzemis, 71, told Reuters. “You don’t know what it’s like to have no family or childhood knowledge. Suddenly all the pieces fitted, now I can find my peace as a person.”

Yet it took Jaunzemis over three decades of tenacious searching to find the vast archive in this remote corner of Germany where his past was buried.

Bad Arolsen contains 30 million documents on survivors of Nazi camps, Gestapo prisons, forced labourers and displaced persons. It rivals Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust centre and the Washington Holocaust Memorial Museum in historical value.

However, many people are not even aware it exists. It was only opened to researchers in 2007 after criticism that it was being too protective of its material. Despite sitting on a mountain of original evidence, it is still struggling to get the attention academics say it deserves.

Last year just 2,097 people visited Bad Arolsen compared with the 900,000 who went to Yad Vashem.

Rebecca Boehling, a 57-year old historian who arrived from the United States in January, wants to change that.

“We have a new agenda,” said Boehling, who came from the Dresher Center for the Humanities at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

“We’re sitting on a treasure trove of documents. We want people to know what we have. Our material can change our perspective on big topics related to the war and the Holocaust.”

Boehling is the first archive director who is not affiliated with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which had managed Bad Arolsen since 1955 with a narrow remit to trace people.

The ICRC handed over the reins to an international commission of 11 countries in January, a step that could help unleash the full potential of the archive for academic study.

Boehling plans to hold international conferences, get foreign students to use the ITS, publish more research and host national teachers’ workshops, although she doubts the 14 million euro budget from the German government will stretch that far.

Personal stories about victims, which the ITS can provide in abundance, are a powerful tool in educating young generations, she said. Currently, events hosted by the archive are attended only by townspeople and groups of pupils from nearby.

SCHINDLER’S LIST

Located next to a site where Hitler’s SS officers once had barracks, Bad Arolsen was chosen for the archive after the war because of its central location between Germany’s four occupation zones.

But now its location is a disadvantage. There are no big cities nearby and connections to Berlin and Frankfurt are slow. The town itself, on the northern edge of the state of Hesse, has a population of just 16,000.

The archive is housed in an inconspicuous white building containing clues to the fates of 17.5 million people.

The 25 kilometres of yellowing papers include typed lists of Jews, homosexuals and other persecuted groups, files on children born in the Nazi Lebensborn programme to breed a master race, and registers of arrivals and departures from concentration camps.

It even has a carbon copy of Schindler’s List, the 1,000 Jewish workers saved by German industrialist Oskar Schindler.

The Nazis’ meticulous record-keeping stopped only when Jews and other victims were herded into gas chambers.

“At death camps like Sobibor or Auschwitz, only natural causes of death are recorded – heart failure or pneumonia,” said spokeswoman, Kathrin Flor. “There’s no mention of gassing. The last evidence of many lives is the transport to the camp.”

The ITS still receives 12,000 enquiries a month and reunites up to 50 families a year, even though the number of Holocaust survivors is dwindling. This tracing work will continue.

Most enquiries come from Russia and Eastern Europe and Boehling welcomes the new phenomenon of grandchildren and great grandchildren, who have more emotional distance from the war, wanting to find out the fates of their relatives.

One major ongoing task is the digitalisation of records which will make it easier for outsiders to carry out keyword searches which had previously been impossible as everything was done in-house with a filing system based on name cards.

Despite its remote location, Boehling says the archive won’t be moved. It has become a something of a memorial for Holocaust survivors, like former Auschwitz inmate Thomas Buergenthal who visited the centre in 2012 after getting new information on where his father had perished.

Buergenthal, who escaped Nazi shooting squads, Auschwitz gas chambers and a death march before he was 12, was found by his mother in a Polish orphanage in 1947 through the Red Cross.

“This is my hallowed ground,” Buergenthal, 78, told Reuters from his U.S. home.

“These documents are more important for the future than for the past. They will be the common heritage of mankind of what really happened during that period. (They are) what we need to prevent it happening elsewhere in the world.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.