These 5 European Jews Are Backing Far-Right Parties

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

(JTA) — They speak different languages and live in different countries. Some of them are strictly observant. Others don’t even keep kosher. Some are Sephardi, others are Ashkenazi.

As diverse as the Jewish communities to which they belong, the Jews who promote Europe’s rising nationalistic parties are nonetheless united in their fear of radical Islam, support for Israel and willingness to endorse politicians who are reviled and considered racist by the mainstream.

Amid historical electoral gains for parties that wish to break up the European Union and ahead of a fateful presidential vote in France, JTA talked to four prominent Jews from parties that are widely considered to be far right in France, the United Kingdom, Austria and Sweden. A Dutch Jewish candidate declined an interview.

France

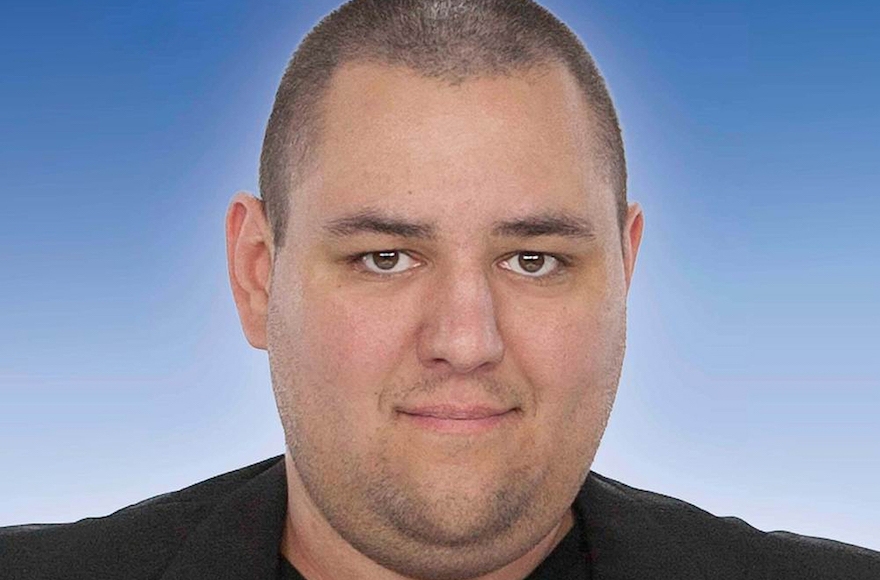

Michel Thooris, 36

Profession: Police officer

Political involvement: Member of the Central Board of the National Front party

Just months after the 2006 murder of Ilan Halimi, Michel Thooris joined the party whose current leader, Marine Le Pen, is leading in the polls ahead of the presidential election in April.

To Thooris, the murder of Halimi, a phone salesman who was abducted for ransom because he was Jewish, heralded a string of “Islamist terrorist attacks that form the No. 1 threat to Jews in France,” he said. Thooris was outraged by some mainstream media’s failure to note the Islamist affiliations of members of the gang that murdered Halimi after torturing him for weeks.

Amid an explosion of anti-Semitic violence in France that started in 2000, and following days of rioting in heavily Muslim neighborhoods near Paris and beyond in 2005, Thooris was drawn to National Front’s promise to “stop lawlessness and Islamist fundamentalism,” as he described it.

Today he heads the Association for Patriots of Jewish Faith, a small group of French Jewish supporters of the National Front.

“Betraying French Jews is not voting National Front but continuing to vote for candidates whose inaction is threatening the community’s very survival,” said Thooris, a Sephardic Jew who goes to synagogue only on some holidays and does not keep kosher. “After Donald Trump’s election, after the vote in Britain to leave the European Union, more and more French Jews are asking: Why not us?”

National Front opposes any concession to the religious sensibilities or needs of Muslims. Its founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who has multiple convictions for Holocaust revisionism and anti-Semitic incitement, was pushed out of the party by his daughter Marine, who succeeded him as party president in 2011.

“His statements were deplorable and unacceptable,” Thooris said.

Thooris was recruited to National Front by Louis Aliot, Marine Le Pen’s life partner. Aliot, who himself has Jewish roots, was looking to reach a wide electorate while distancing the party from the provocations of its founder.

Marine Le Pen has largely purged the party of members who made anti-Semitic statements.

In a country where Jews “risk getting shot at kosher supermarkets or at their schools, Marine is the best candidate to protect us,” said Thooris, whose mild manner and attention to nuance differs greatly from the feisty and bombastic style of the presidential candidate.

But the protection may come with a price for some Jews, Thooris acknowledged.

“We don’t idolize Marine, nor do we agree with all of her platform points,” he said.

One point of discord is National Front’s neutrality on Jerusalem. Another is Marine Le Pen’s calls to outlaw wearing the kippah in public — collateral damage in her planned ban on wearing any religious symbols in public, which she concedes is designed to limit expressions of the Muslim faith.

“In reality, Jews are already prevented from wearing kippah in public in many areas for fear of attack,” Thooris said. Even if a ban materializes, “Jews can always wear a hat,” he added.

According to a 2014 poll, 13.5 percent of Jewish respondents said they would vote for Marine Le Pen. Support for her father among Jews was nearly nonexistent.

“Supporting National Front is no longer a taboo among French Jews,” Thooris said.

The United Kingdom

Shneur Odze, 36

Profession: Politician and rabbi to several Manchester-area Jewish communities

Political involvement: The mayoral candidate in Manchester of UKIP, the UK Independence Party

Shneur Odze, a haredi Orthodox rabbi and follower of the Chabad Hasidic movement, was politically active at 18. The native Londoner became a member of the Conservative Party until he “drifted away” from the party over its “opportunism and lack of ideology,” he said.

Back then, Odze still feared that UKIP might be “the far right in blazers” — a politer version of Conservative former Prime Minister David Cameron’s description of UKIP in 2006 as consisting of ”fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists mostly.” In 1999, UKIP “wasn’t something I’d jump into bed with,” said Sodze.

The anti-EU movement is suspicious of immigrants, especially Muslim ones. One of UKIP’s most senior spokesmen, Gerard Batten, wants Muslims to sign a declaration rejecting violence. And a UKIP European Parliament lawmaker, Stuart Agnew, in 2015 supported banning ritual slaughter of animals both by Jews and Muslims in an apparent attempt to target the latter, though the party’s former leader, the flamboyant orator Nigel Farage, did not support the proposal, which never became policy.

But following a series of meetings with UKIP leaders, Odze realized several years ago that they were “not far-right bigots as the mainstream left-leaning media would have you believe, but rather kindred spirits” of his. The party “was the natural home” for him and anyone for whom “British identity means something more than warm beer and cricket on Sunday morning.”

Jewish community groups, representing the descendants of immigrants who fled persecution in Eastern Europe and Spain, are deeply critical of UKIP’s platform of drastically reducing immigration and ending foreign aid.

But Odze, an eloquent speaker who has studied in Israel and is fluent in Hebrew, says UKIP’s insistence on British patriotism is reflected by Jewish tradition in Britain. He cited the prayer offered in British synagogues for the good health and wise counsel of the queen.

“I didn’t believe that a nation that is increasingly insecure about its own direction and purpose can protect its Jewish population,” Odze said.

He campaigned feverishly ahead of the June 2016 referendum in which a majority of British voters supported a British exit from the European Union – a result that UKIP strongly supported.

His appearance, Odze said, made him “more accessible to people with an immigrant or minority background” who contemplated voting to leave but feared it would strengthen xenophobia — including “Muslim cab drivers whose jobs were being taken over by immigrants from Poland.”

Within the Jewish establishment, he said, “there was overwhelmingly shock, horror and amazement” at his UKIP role. But the regular Jew on the street “found it interesting, if not amazing,” Odze added, and one of his congregants recently told him that voting UKIP is his “guilty secret.”

The Netherlands

Gidi Markuszower, 39

Profession: *Businessman

Political involvement:* No. 4 in the Party for Freedom of Geert Wilders** **

As a pupil attending Amsterdam’s only Jewish high school in the 1990s, Gidi Markuszower was something of an oddball for his support of Benjamin Netanyahu, leader of the right-wing Likud party in Israel and the country’s prime minister.

Belonging to a community with strong left-leaning traditions, many Dutch Jews passionately supported the 1994 Oslo Accords.

“The whole school fought with him,” Zvi Markuszower, Gidi’s father, told the NRC daily in a profile published about the politician earlier this month. But Gidi “didn’t mind. He likes it when people disagree with him.”

Twenty-five years later, many Dutch Jews still passionately disagree with Gidi Markuszower’s decision to join the far-right Party for Freedom of the anti-Islam provocateur Geert Wilders.

Wilders’ 2011 decision to support a ban on ritual slaughter, aimed primarily at Muslims but also including kosher slaughter, left many Jews skeptical of his oft-stated commitment to “Judeo-Christian values.” His promise in 2014 to make sure the Netherlands has “fewer Moroccans” alienated even some of his right-wing supporters from within a Jewish community sensitized by the Holocaust.

But Markuszower, who was born in Israel and raised with his two brothers in the Netherlands by modern Orthodox parents, is far from an anomaly. A survey earlier this month showed that the Party for Freedom is the third most popular among Dutch Jewish voters, with 10 percent of the vote. In the March 15 general elections, the party won 20 seats out of 150 in the Dutch lower house, for the first time becoming the second-largest party in the Netherlands.

For Dutch Jews, part of the Wilders allure is his stated attachment to Israel, where he lived for two years in the 1980s and describes as the West’s “first line of defense” against Islam.

In the NRC profile Markuszower, who declined to be interviewed by JTA, was described as a polite “gentleman” who is loyal to Wilders and does not seek media attention. But he received plenty in 2010, when he was forced to withdraw his candidacy in that year’s parliamentary election following a scandal that followed his arrest years earlier for carrying an unlicensed firearm while working as a volunteer guard for the Jewish community.

Then-Interior Minister Ernst Hirsch Ballin, whose father was a Jewish Holocaust survivor, threatened to take action against Wilders’ party if it presented the candidacy of Markuszower, whom Ballin flagged as a threat to national security, according to NRC.

But the real threat, Markuszower told Haaretz that year, was from Muslim perpetrators of anti-Semitic violence.

“People are afraid to wear a skullcap on the street for fear of attack,” he said, “and this is the result of violence by Muslim immigrants.”

Austria

David Lasar, 64

Profession: Political strategist, local politician, former newspaper stand owner

*Political involvement: *Lawmaker for the Freedom Party

Vienna’s small Jewish community of 8,000 was shocked when David Lasar decided to run for office in the 2005 City Council elections on the Freedom Party ticket — a movement founded in 1956 by a former SS soldier whose leaders and members have been responsible for a steady stream of scandals involving anti-Semitic speech and Nazi imagery.

It was, to say the least, an unusual choice for a Jew who lost many relatives during the Holocaust. Jewish journalist Karl Pfeifer accused Lasar of serving as a “fig leaf for closet Nazis.”

In addition to its historical baggage, the Freedom Party features an anti-Muslim agenda that includes a ban on the construction of mosques, a shutdown of immigration and a prohibition on ritual slaughter and public prayers.

But unlike other European Jews who represent far-right movements, Lasar was condemned in the Jewish media and widely shunned for his political choice.

Like his counterparts from other European far-right parties, Lasar insisted that the Freedom Party, which he joined in 1998, has been rehabilitated from anti-Semitic tendencies. He credited the leadership of Heinz-Christian Strache, who has headed the party since 2005.

“All the anti-Semitic people have been removed. We can prove that. And for years now we have a pro-Israel policy,” Lasar told JTA in an interview.

Citing the participation by party leaders in Holocaust commemorations, he said the Freedom Party is “doing more than other parties” to honor the victims of the genocide.

“The new anti-Semitism in Austria, in Europe, is being imported and spread by Islam,” Lasar told the Washington Post last year. “It’s important that Austria maintains a Judeo-Christian tradition. Islam is not a part of that.”

Eager to shed its negative image and deflect accusations of racism, the Freedom Party has highlighted Lasar’s membership consistently since 2005, when it noted in a not-so-subtle statement to the media that he is “not only a member of the religious community, but also has excellent international contacts.”

Lasar insists the Freedom Party, whose candidate last year narrowly lost the presidential elections, is not using him as a prop.

Sweden

Kent Ekeroth, 35

Profession: Politician

Political involvement: Lawmaker for the Sweden Democrats

When Kent Ekeroth was born in Malmo, it was a quiet place known to relatively few people outside Scandinavia.

Since then, the city of 300,000 — one-third of whom are immigrants from Muslim countries — has become known as an example of the immigrants’ failed integration. Frequent expressions of anti-Semitism by immigrants and some far-left politicians, including the previous mayor, have left Jews shaken and led to travel warnings by the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

Against this background Ekeroth, a Swedish-Jewish lawmaker for the rightist Sweden Democrats party, no longer feels safe in the city where he lived until age 4, when his parents moved elsewhere in southern Sweden.

“I don’t feel particularly safe anywhere in Sweden because security isn’t very good anywhere. But it’s worse for women,” Ekeroth told JTA.

He blamed the formation of “ghettos where the dominant culture reinforces terrorism,” referring to heavily Muslim neighborhoods.

“We’re certainly critical of a religion that is too often shown to be incompatible with Western values,” he added when asked whether Sweden Democrats was anti-Muslim.

Critics of the party in Sweden accuse it of espousing racist views.

October was a particularly bad month for the Sweden Democrats. A party lawmaker called for action against what she labeled the “control of media by any family or ethnic group,” citing a prominent publisher with Jewish roots.

Senior lawmaker Carina Herrstedt was widely criticized in the media for writing a racist joke in an email that was deemed offensive to gays, blacks, nuns, Roma and Jews. Finance spokesman Oscar Sjöstedt was heard in a recording jokingly comparing Jews to sheep being killed in German abattoirs.

In January, these scandals and others prompted 40 Swedish Jews to call for a boycott of Holocaust commemoration in the city of Gothenburg, whose organizers included the local Sweden Democrats.

Yet Ekeroth says the party’s leadership bans racist rhetoric.

“Every party attracts some anti-Semites,” he said. “I don’t want any anti-Semites in mine. I want them to be kicked out.” Regarding anti-Semites, he added, “the ones on the left are no better.”

The former mayor of Malmo, Ilmar Reepalu of the Social Democratic Party, is a case in point. Over the years he has said that Zionism and anti-Semitism were both “unacceptable forms of extremism,” that the Jewish community had been infiltrated by nationalists, and that Jews who don’t wish to be assaulted should not support Israel. In 2012, Erik Ullenhag, Sweden’s integration minister at the time, called Reepalu “ignorant and bigoted.”

Above all, though, Ekeroth said Jews should support the Sweden Democrats because “it is the best friend that Israel has got in Swedish politics, where is doesn’t have too many friends.”

Israel’s Foreign Ministry doesn’t see it that way.

In December, Deputy Foreign Minister Tzipi Hotovely declined to meet with a Sweden Democrats lawmaker who was part of a delegation of U.S. Republican and European politicians. The delegation was led by Becky Norton Dunlop, who was a member of then President-elect Donald Trump’s transition team. Norton Dunlop canceled the meeting with Hotovely to protest the snub.

Ultimately, however, the cold shoulder from Israel and some Jews to right-wing parties that seek their endorsement will not harm the rightists, Ekeroth said.

He noted that Sweden Democrats has more than doubled its gains in the 2014 parliamentary elections, leaving the party with 49 seats out of 349 in parliament.

“Right-wing movements are on the rise not only in Europe,” he said. “The strategic thing to do would be to make friends with friendly forces instead of shunning them and turning them into an enemy in the long run.”