He’s an 80-year-old shoe designer, philanthropist – and competitive table tennis player

Stuart Weitzman, who competed in his fourth Maccabiah Games, has donated millions to help others participate

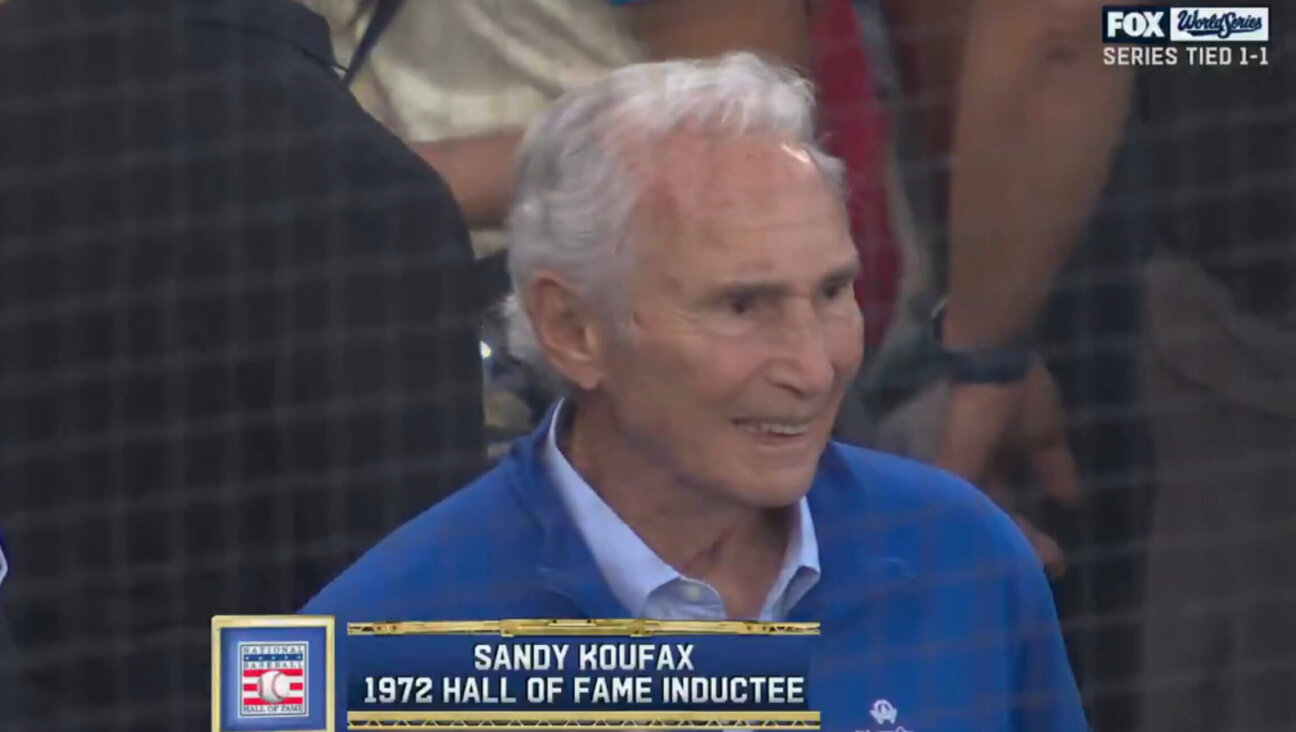

Shoe designer Stuart Weitzman in 2008. Photo by Getty Images

RAANANA, ISRAEL – At a high school gymnasium here, an American man sporting a coronavirus mask carried a plastic bag containing his wallet, cellphone and table-tennis paddle while mingling with fellow players at the Maccabiah Games, the largest Jewish sporting event in the world.

His black sneakers were Skechers, not Stuart Weitzmans. The man, though, was Stuart Weitzman, the legendary designer of women’s footwear who earned fame and fortune with his designs and outfitting celebrities for red-carpet events.

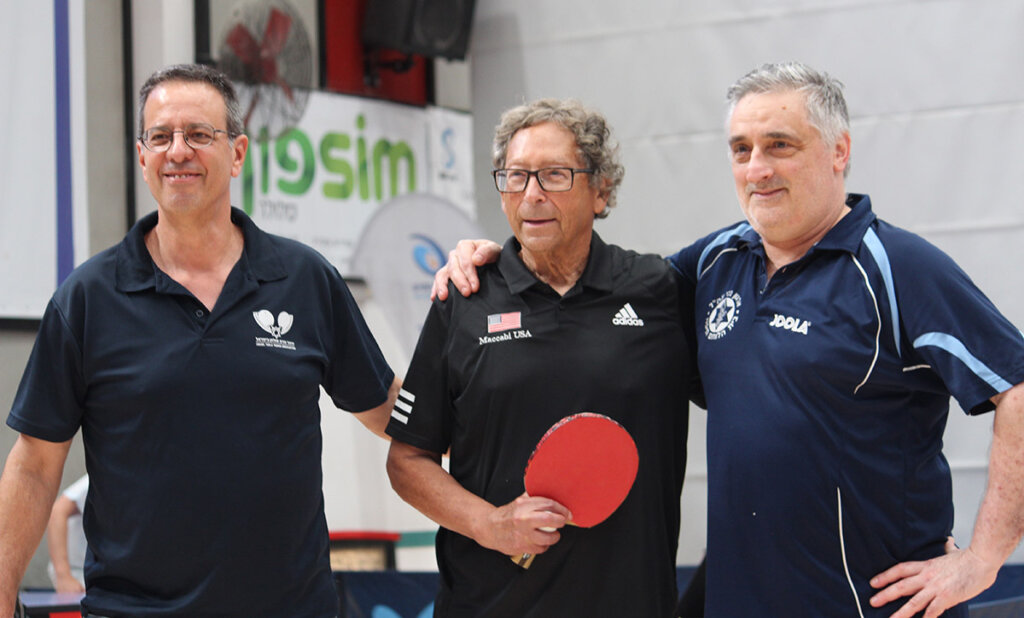

Wearing a black T-shirt and black shorts, he didn’t scream fashionista. He was just Stuart the table-tennis player, a genial man nearing 81 competing in his fourth consecutive Maccabiah in the over-60 category of athletes.

On two afternoons last week, a reporter observed Weitzman consistently in motion, very much at ease, reveling with those in attendance. He practiced with anyone available, played his matches, cheered on teammates and caught up with familiar faces. He chatted with teenage players, a Mexican rabbi who’d defeated him hours earlier and a high school classmate visiting Israel to watch her tennis-playing daughter compete.

Samuel Parasol, an Australian table-tennis competitor also retired from a career in women’s fashion, once mentioned to Weitzman about his son’s upcoming nuptials.

“Stuart said the bride can go to one of [his] stores in Melbourne and pick out whatever she’d like” for the wedding, Parasol said. “It shows what a genuine, decent, caring guy he is.”

The Uruguayan, Argentinian, Mexican and Cuban players here appeared to give Weitzman his greatest joy. He’d stop them to converse in Spanish, a fluency developed from spending so much time in Spain at his shoe factory – he set up ping-pong tables there for workers – of his eponymous company. Spain also is home to two of Weitzman’s philanthropic projects: preserving the cave of La Garma, an archaeological site dating back to the Paleolithic age, as well as helping to build a Spanish-Jewish museum in Madrid.

Weitzman was impressed by the diversity of Jewish athletes at the Maccabiah Games. “Most can’t speak the same language – but they love each other,” Weitzman said from second-floor seats, surveying players of multiple nationalities practicing below. He held up a red T-shirt a Cuban player had just traded him.

“I saw a kid from Panama wearing tzitzis – fringes. I saw three girls from Argentina looking at these three boys, basketball players. They were hunks. They went for a drink together. They were all about 18. It was so sweet, so wholesome to see.”

A $5 million donation

Weitzman is intent on bringing young U.S. athletes to the Maccabiah Games who otherwise couldn’t afford to pay the $8,000 participation fee.

He established a challenge-based grant last year: He’ll contribute $5 million to Maccabi USA, the sports movement’s American arm, if other donors chipped in $3 million. About one-third of the $8 million has been raised so far.

“I cashed that $2 million check in January. It was fun to do,” said Joel Roodyn, treasurer of Maccabi USA’s endowment fund and Weitzman’s table-tennis teammate, of the first-stage donation. Roodyn and Weitzman both earned bronze medals in the team competition here.

Roodyn said the initiative is “a game-changer for us” by enabling up to 300 Americans to compete at each Maccabiah on a needs-only basis. Under terms of the gift, up to 10 percent may be spent to bring non-U.S. athletes to each Maccabiah, he added.

The donation arose from “my love for” the event, explained Weitzman, tracing his sports fandom to his childhood in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens, N.Y., where he excelled at tennis and table tennis. (Weitzman still has the home run ball he caught on Bedford Avenue, outside Ebbets Field, off the bat of Duke Snider, the Brooklyn Dodgers slugger.)

“I see what it does for kids all over the world,” Weitzman said of the Maccabiah. “The challenge was just another way to get other people involved.”

Weitzman’s philanthropy includes rescuing Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History when banks were poised to seize it, and endowing the school of design at the nearby University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater. Both buildings now carry his name.

While attending Penn, Weitzman made a sketch of women’s shoes for his friend’s father. The design was manufactured, and seeing his creation in the window of the man’s Fifth Avenue store, Weitzman said, “was pretty exciting.”

“He liked it. I never looked back,” he said.

Weitzman did glance back on July 14. He bore the U.S. flag, about to lead the 1,300-person U.S. delegation into Jerusalem’s Teddy Stadium for the Maccabiah’s opening ceremony. He turned for a last, pre-procession look.

Seeing so many Americans behind him “was pretty cool,” he said.

Weitzman could return to the country before any of them. He said he’s considering spending two or three months a year in Israel.

“All the guys go down to Florida in the winter. After a while, it gets boring,” said Weitzman, who lives with his wife, Jane, in Connecticut and Manhattan. The couple celebrated their 55th anniversary in Israel last week. “Israel beats Palm Beach. You feel at home. Plus it’s got sun, the ocean, good restaurants, sports and culture galore. It’s got everything. I love it.”