Abraham Lincoln the Jew

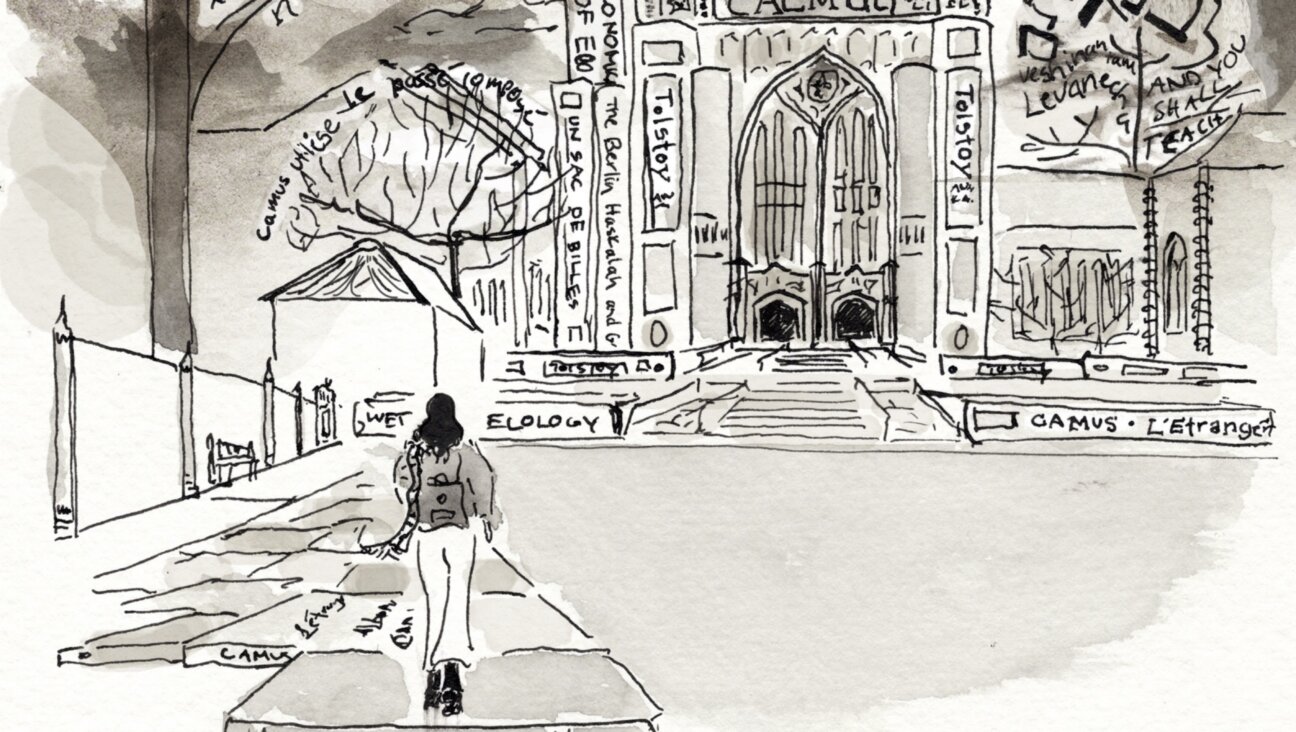

Image by getty images

“He,” a somber Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise intoned after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, “is a sin-offering for our iniquities.” This sentiment, expressed in a black-draped congregation in Cincinnati, was echoed in countless other memorial services across the North. Peace had been declared but days before; now, synagogues recited the Kaddish for the fallen president.

In New York City, Shearith Israel broke with custom by chanting a Sephardic mourning prayer it had never before said for a gentile. Jews were in the midst of celebrating Passover; now Lincoln, like Moses, had succumbed at the threshold of the Promised Land. In Cincinnati, Wise ended his sermon with words that may have stunned his hushed audience (we have no record of the response). “Abraham Lincoln,” he proclaimed, “believed [himself] to be bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh. He supposed [himself] to be a descendant of Hebrew parentage. He said so in my presence. And, indeed, he preserved numerous features of the Hebrew race, both in countenance and character.”

Those who seek to cultivate this claim will find it to be rooted in thin soil. Efforts to construct a Hebraic lineage that connects Lincoln’s lonely log cabin in Kentucky with Mount Sinai must rely more on wishful thinking than on fact. Likewise, there are more parochial explanations for Lincoln’s rhetoric, lush with biblical imagery, than a Jewish upbringing. Lincoln’s friendship with Jews reveals relatively little beyond an absence of prejudice.

His most intimate Jewish acquaintance seems to have been Isachar Zacharie, his self-promoting chiropodist, whom he entrusted with a secret diplomatic mission during the war (in subsequent retellings, Zacharie has become the most, perhaps the only, celebrated foot doctor in Jewish history). And Lincoln’s responsiveness to Jewish concerns during the Civil War — his support for efforts to amend a congressional statute that barred non-Christians from the military chaplaincy, and his rapid countermanding of an anti-Semitic order issued by his most successful general — bespeak his genius as a president rather than tribal solidarity.

Instead, Wise’s words — almost certainly one of his occasional flights of fancy — are more intriguing for what they reveal about how Jews have thought about Lincoln since his death than for what they can tell us about Lincoln himself. Wise’s efforts to claim the departed president as a Jew were an early example of an incipient “cult of Lincoln” that has been embellished over time.

Although Jews are far from alone in idolizing Lincoln, he has been, as Beth Wenger (director of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Pennsylvania and historian of American Jewry) has demonstrated, a versatile symbol for synagogues, socialists and Zionists since 1865.

American Jews have imagined and reimagined Lincoln in a variety of ways to demonstrate their patriotism, belonging and alignment with American values. Others have focused their attention on the handful of Jews who entered Lincoln’s orbit, basking in the reflected rays of his greatness. Why else, for example, do we know (and care) that it was Edward Rosewater, a Jew, who transmitted the Emancipation Proclamation by telegraph from the office of the War Department? By associating themselves with the revered figure of “Father Abraham,” Jews (and others) have burnished their own image and self-perception.

Indeed Wise’s memorial sermon itself suggests how fickle and malleable memory and commemoration can be. After all, his eulogy represented a striking volte-face. In 1860, Wise had opposed Lincoln’s candidacy for president, describing him as a “country squire who would look queer in the White House with his country manner.” As recently as a year and a half before the assassination, the rabbi had publicly identified with the “Copperhead” faction of the Democratic Party, known for the ferocity of its attacks on Lincoln’s administration.

Although his politics were more radical than those of many of his co-religionists, his preference for the Democratic Party (rather than Lincoln’s Republicans) was not atypical of American Jews, particularly in the election of 1860. During Lincoln’s lifetime, Jews, and many others in the Union, were ambivalent about their wartime president; following his death, they joined their countrymen in pronouncing Father Abraham a sainted martyr, and at times claimed him as one of their own.

Adam Mendelsohn is the co-editor, with Jonathan D. Sarna, of “Jews and the Civil War: A Reader” (NYU Press, 2010).