A Father’s Pain at Overseeing Son’s Circumcision

Image by getty images

I’m in the shower at 6 a.m. with a sick feeling in my gut. Today, my 8-day-old son is going to be circumcised.

This is my third round, and many people told me this time would be easier — and being an Orthodox Jew who embraces ritual in his life, you’d think it would be. But it isn’t. The first time was bad, but it all happened quite quickly so there wasn’t time for the horror to build up. I don’t remember the second one so clearly, only that it wasn’t good.

But this time I’ve felt especially close to the baby, spending the first few hours of his life alone with him while my wife was rushed into surgery for a minor emergency procedure. And my life is different now. I’m three years into my psychotherapy training, I’m more in touch with my nurturing instincts.

So it feels really alien to choose to inflict pain upon my son, to put him through the trauma of a minor procedure without anaesthetic.

Why am I doing this? What has possessed me?

God apparently told Abraham to do it, to walk before Him and be perfect.

The Forward wants to tell readers stories about circumcision. Tell us your experiences with the rite

I don’t feel perfect. I feel far from perfect.

We’ve been doing it for thousands of years.

I don’t buy that argument. Mankind has been doing horrendous things for thousands of years: slavery, capital punishment, condemning homosexuals, oppressing women.

That is not a club of actions I want to be part of: I believe in moral progress, in the continuous unfolding of values, in progressive enlightenment and revelation. When we justify with reference to precedent, when we cede the authority of our own heart and conscience, that is when we begin to step into darkness; that is when we unleash all manner of regressive passions and practices upon the world.

I don’t live that way, I don’t want to live that way, I don’t ultimately believe anyone should live that way.

I’m confused.

I stand in silence during the Amidah hoping for inspiration, for some clarity or ease of mind. But the torment increases, more than ever I don’t know who I’m praying to; the source of value and truth in the world is hidden. Where a bright light normally shines there is today merely darkness and clouds. I am abandoned, adrift, cut off from the root of life.

The moment gets closer. I check to see if my wife has arrived with the baby. Perhaps she hasn’t, perhaps she’s made good on her half-joking comment that she would just run off with him and disappear. How wonderful that would be.

We wait, nervously, fellow fathers who’ve also been here before checking in with me, seeing how I’m feeling. “Kierkegaardian” is all I can respond.

Kierkegaard wrestled with the binding of Isaac, with the absurd God who demands that we abandon the ethical plane. He knew this was too much, and it hounded him. I never really got his resolution, his talk of the necessary leap into the absurd, of that being the true faith. I mean, I see that faith is often a leap, but I’m not sure it’s that kind of leap. And I get that the ethical is not always everything, that it is sometimes suspended in a clash of values. But not here, not like this.

The baby is coming into the room. “Just call it off. Stop the whole thing,” I find myself thinking. I have a vision of acting on this, of carrying it out, of sending everyone home. How would people respond? Would we have the capacity as a group to handle this, to process it?

Circumcision is the great unspoken, the great unconsidered. It’s only ever on anyone’s mind for a few days, and then, as evidence of how painful it is, it is forgotten. If it were in our face as a community regularly, repeatedly, like women’s issues or homosexuality, then I feel more objections might gather, some kind of outrage might start to brew. But it leaves us quickly, and perhaps as lone individuals, as troubled parents, we aren’t given enough room to think about it.

I don’t stop it. I can’t stop it. The baby arrives; we still haven’t named him. Would it be harder to do this if he already had a name, if we’d really come to terms with his individuality?

I hold him. I gaze at him and ask for forgiveness. What on earth am I doing here?

I put him on the chair, and the prayers begin. But I’m not letting go of him. I hold his hand; I try to be there for him, to retain the connection. If the idea is that I should renounce him, that my bond to him should weaken, I’m not having that. No way.

I noticed myself subtly withdrawing from him on the previous day, feeling slightly less close to him. That’s me defending myself, trying to ease the pain, trying to loosen the grip of horror. I’m sure I’ve done that before, but I’m now better trained to notice it.

No, this is my son, our son. We brought him into the world to care for him and love him, and we will not go back on that, we won’t abandon him or offer him up. I will stay close to him, and whatever pain he feels, I will feel.

People said I should look away. Are you kidding? I should put him through that and I shouldn’t even be strong enough to actually watch it, to witness it? That would be disgusting — cowardly, hypocritical, shameful.

If he’s going to experience it, then so am I. As closely as possible.

The diaper comes off as my father holds the baby. It’s a small mercy that the baby screams every time his diaper comes off. That takes a little of the edge off this particular scream.

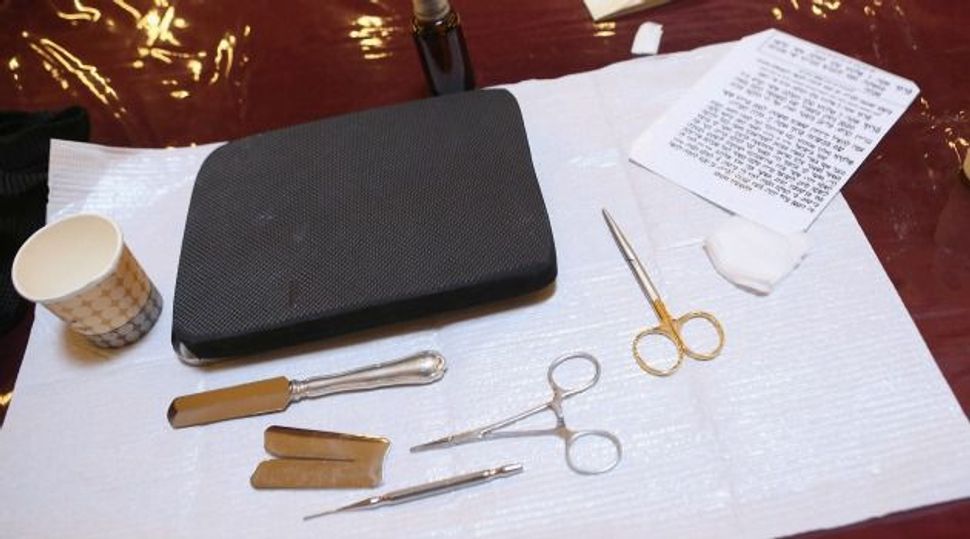

But then the mohel starts using his tools, separating the foreskin, poking and gripping it carefully. And then the clamp goes on.

Here we go. It’s like the final moments of ascending a huge rollercoaster climb. The adrenal fear is peaking.

I know the mohel’s trick: He tries to direct you to read the brakha, the blessing, so that you miss seeing the actual moment. I’m not falling for it; my eyes are glued to the clamp, to the foreskin. I have to see this, to know what I’ve done.

He checks to make sure that I don’t want to do it myself. I assure him that I don’t. I suppose I should, that I should really experience the horror of cutting him myself. But it’s much easier not to; this way we can almost convince ourselves it’s a medical procedure, a palliative fabrication helped by the mohel being a doctor.

I watch carefully. And with a quick flick of his wrist, the deed is done. There is blood, and there is screaming.

It’s my turn to say the brakha — to praise God, who has commanded me to bring my child into the covenant of Abraham. I feel very ambivalent. I’m generally proud of the Abrahamic tradition; I feel enriched by rooting myself in that much history. But isn’t there a less traumatic way to forge the connection?

Some might argue that it should be traumatic, that without a little trauma there’s no sacrifice. And without the price of sacrifice you can’t be part of the club.

The thought leaves me cold; I’m not sure I want to join a club that prizes the trauma of afflicting our children in this way.

The deed is done. My finger is straight into his mouth, something to suck on, to soothe him, along with plenty of Kiddush wine. Anything to ease the pain for both of us — anything at all.

My wife speaks beautifully, movingly, and there’s barely a dry eye in the house. Everyone gets that we’re doing this with difficulty.

At the other britot I felt better once it was done, relieved it was over, relieved there were no complications.

Not this time. This time I still feel sick, and as everyone comes to wish me mazel tov I can’t help but let them know that I’m not happy about it, that I’m seriously shaken up.

I’m not going to say we need to change this ritual, but at the very least we need to have a conversation about it, to explore what we think and feel about it. If it’s somehow necessary for us to go through this trauma as both parents and children, then it’s doubly necessary that we talk about it, that we give the wounds a chance to breathe.

To do any less would be to curtail our freedom of thought and feeling, to perform upon ourselves the ultimate mutilation.

Elie Jesner is a London-based writer and educator who is currently training as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist. His blog can be found at thinkingdafyomi.com