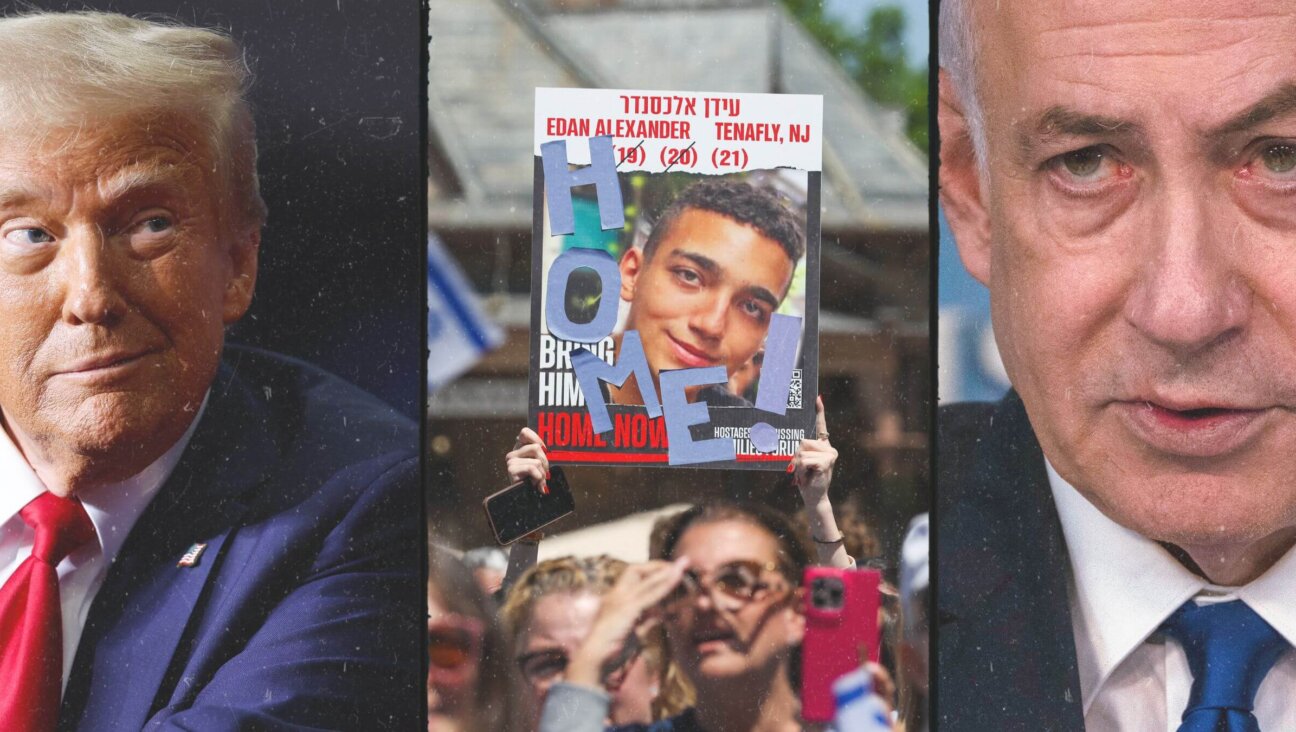

Why Benjamin Netanyahu May Look at the Math — and Cut Deal on Peace Plan

Image by Getty Images

There are plenty of good reasons to doubt whether Benjamin Netanyahu has any real intention of reaching a peace agreement with the Palestinians.

He keeps approving new settlement construction in the territories where the Palestinians expect to build their state. He keeps coming up with new security red lines — control of the Jordan Valley, no yielding on Jerusalem, recognition as the state of the Jewish people — that happen to contradict core Palestinian red lines. And, of course, he’s assembled a governing coalition filled with key players and whole parties that flat-out oppose Palestinian statehood. Even his own Likud party is against it.

On the other hand, there are several very good reasons to suspect that he’s getting ready to make a deal. First of all, his allies on the right seem to think he is. They’re showing signs of panic. Several legislative initiatives are underway in the Knesset to tie the prime minister’s hands — two different bills to annex the Jordan Valley, plus another to require a Knesset super-majority before Israel can enter any negotiations on Jerusalem (this one actually passed the first hurdle, clearing the ministerial committee on legislation) — on the apparent assumption that without such restraints, he will give away the store. Maybe they know something.

Then there’s all the individual maneuvering by senior ministers. The defense minister, Moshe Yaalon, caused a serious international incident with some off-the-record comments that ended up on the front page of the mass-circulation Yediot Ahronot, calling Kerry “obsessive” and “messianic.” For an Israeli defense minister, in charge of managing the most critical aspect of Israel’s most critical relationship, to insult Israel’s most important ally in such a reckless way suggests a mood of extreme anxiety in the country’s senior echelons.

Yaalon isn’t the only one behaving strangely. Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, usually considered one of the most hawkish figures in the cabinet, has been singing Kerry’s praises of late. He speaks of the importance of the secretary’s efforts and declares that Israel won’t get a better deal than the one Kerry is preparing. This seems wildly out of character, but it isn’t. Before ideology, Lieberman is first of all a canny survivor. He’s unmatched in his skill at sensing where the wind is blowing. Right now, it appears, he feels the wind blowing from Washington, and when the dust settles, he doesn’t want to be caught on the wrong side.

Just the opposite is Naftali Bennett, economics minister and head of the religious-nationalist Jewish Home party. He’s been threatening lately to bolt the coalition if Netanyahu signs onto a Kerry framework agreement that involves major territorial withdrawals in Judea and Samaria. He’s worried enough about the possibility that he’s been speaking about it nonstop for weeks.

Bennett met with Netanyahu one-on-one several times in early January to lay out the red lines that would make him leave. He outlined them publicly in a speech in Tel Aviv a few days later: no dividing Jerusalem, no Palestinian state, no 1967 borders, no land swaps. In effect, no to any conceivable Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement in this generation. News reports say Bennett has been meeting with Likud hard-liners, trying to line up a group beyond his own 12-member caucus that would walk out on Bibi en masse.

Bennett’s problem is that his walkout would be pointless. Bibi could replace his hard-line bloc in a heartbeat. Labor and Shas, with 26 Knesset seats between them, would happily join a Netanyahu government that was preparing to embrace Kerry’s plan. (No more than three or four of Shas’s 11 lawmakers back the party’s right-wing ex-leader Eli Yishai; the rest follow old-new leader Aryeh Deri, a confirmed dove.) News reports say United Torah Judaism, with six seats, would also join up. The left-wing Meretz, with six seats, would support the deal from outside the coalition. So would the 11 lawmakers of the so-called Arab parties.

In fact, if Bibi were to present the Knesset tomorrow with a deal along the lines Kerry is developing, creating a demilitarized Palestinian state with borders based on the pre-1967 lines, with land swaps, a symbolic compromise on refugees and a modified reference to the Arab Peace Initiative (which already includes an “end of conflict” clause), he’d get between 72 and 75 votes out of 120, or 60% to 62%, even before the arm-twisting begins.

Bibi knows the math. It puts him in a double bind. He ran for prime minister in 2009 with the intention of rolling back the concessions Ehud Olmert had offered the Palestinians in 2008. He viewed them as too risky from a security point of view. Five years later, he’s hit a wall: The Palestinians aren’t backing down nearly as far as he’d hoped. And in the meanwhile, the rest of the world — even including the Americans — is running out of patience.

This is the part where Bibi’s supposed to stand up and say, No, Israel’s security requires that I draw the line here, even if it means no deal. Unfortunately, five years have also taught him that almost none of Israel’s security professionals — the people whose job it is to read the landscape, analyze the enemy’s intentions and win the wars — agree with his analysis. As they see it, the greatest threat to Israel is to go another generation without an agreement. He’s gone through three national security advisers, replaced the heads of all the intelligence services, shuffled and reshuffled, but whoever he comes up with tells him the same thing.

Take Kerry’s plan for Jordan Valley. It’s not the Israeli military’s dream scenario, but it’s the best that has a chance of winning Palestinian acceptance. In fact, the Israeli military helped design it. That makes it harder for Bibi to reject it. That’s bind number one.

Bibi can argue, and rightly so, that generals and spooks don’t make national policy in a democracy. That’s what elections are for, and he was elected prime minister. If he doesn’t like the deal, it’s his prerogative to say no.

On the other hand, when he looks at the elected Knesset, he realizes that the Israeli voters didn’t vote for a government that would say no. Upwards of 60% voted for parties that would say yes. That’s bind number two.

It’s not just American pressure that’s pushing him toward the painful compromises he vowed never to make. It’s the will of the Israeli public.

His allies on the right see how torn he is. That’s why they’re panicking.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

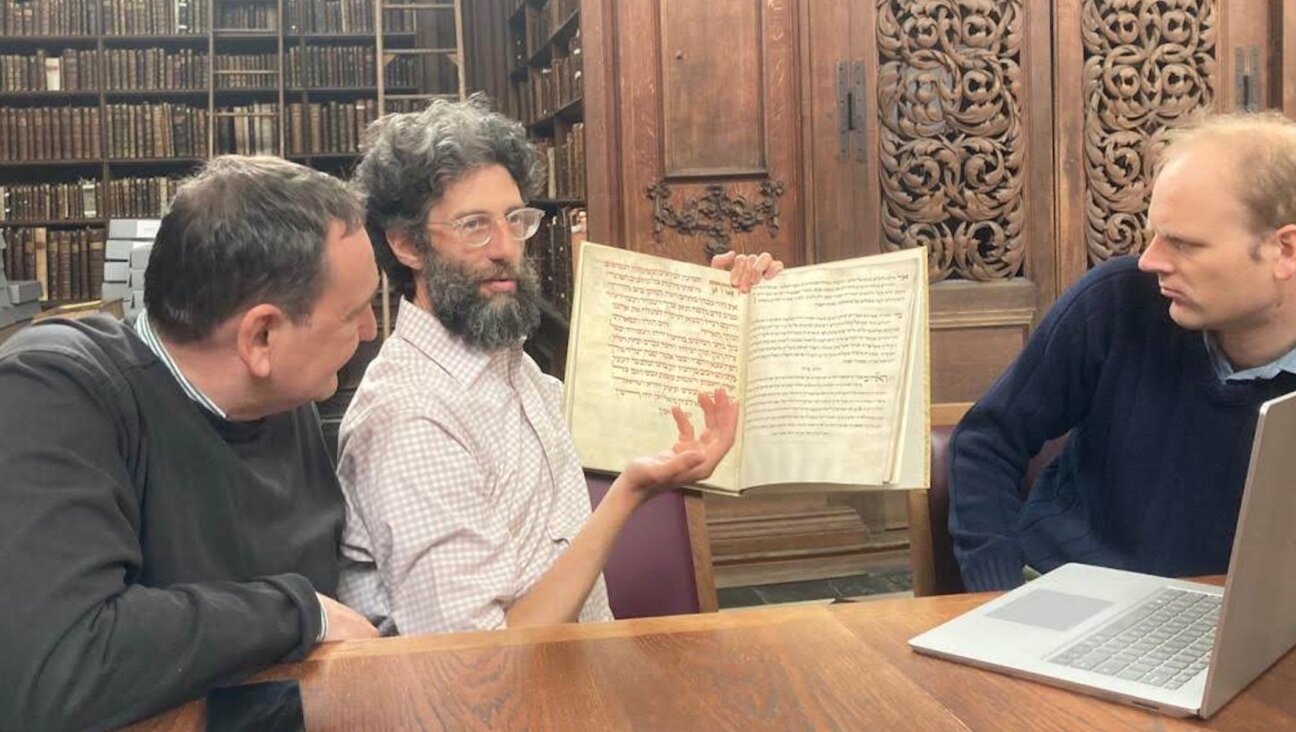

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.