Why Nate Silver Should Listen to Abraham Joshua Heschel

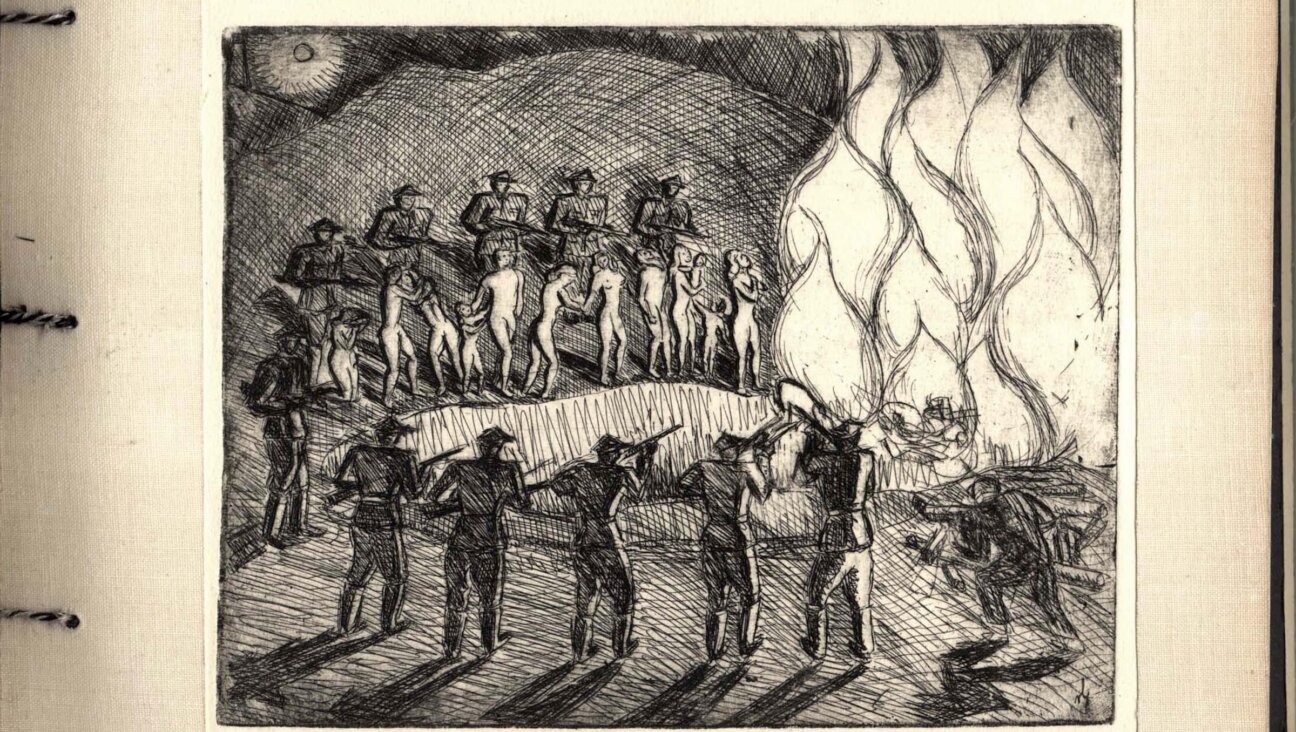

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Nate Silver has pissed a lot of people off lately.

In an interview with New York Magazine about the then upcoming launch of the new FiveThirtyEight site, the data-journalism enthusiast took a jab at traditional opinion journalism. He told the interviewer that pundits might “have really high IQs, but they don’t have any discipline in how they look at the world, and so it leads to a lot of bullshit, basically.” He went on to say that the op-ed columnists at the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal, “don’t permit a lot of complexity in their thinking. They pull threads together from very weak evidence and draw grand conclusions based on them.”

Silver’s approach, as he explains it, is more quantitative, rigorous and empirical. Whereas others rely on ideas, his relies on the invincibility of numeracy. He never outright says that this makes what he does better than what opinion journalists do, but he does imply that data journalism is better suited to deliver large truths.

The purpose of journalism is to maintain an educated society, a populace that has the facts in hand to make good decisions for themselves and the wider world. Silver thinks his research-based approach, a blending of numbers and analysis, can better fulfill this mission. Oped columnists and outspoken Silver critics like New York Times Paul Krugman and the New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier disagree. They see data as important, but, in Krugman’s words, “never a substitute for hard thinking.”

So what is the best way to get people to better understand themselves and how they should behave? Is it evidence or exegesis, computations or consciousness, data or deliberating?

The answer, for the Jews, has long been been all of the above. Substitute the word of God for science, and you’ll find that our tradition is built of these two opposing forces whose coming together formed the great texts that have served as the nucleus of our mostly nation-less people for a long, long time.

The Jewish canon, which includes the Torah, Mishnah, Talmud, Zohar, and other texts, is a mixed bag of law, poetry, and stories, stories about stories, including some super-duper strange hallucinatory tales. At its center is the Torah and its laws; the facts, as, many long-believed and some still do, which were given to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai. Embroidered around it are a thick tapestry of projections, opinions, fantasies and doubts, all of which, in my opinion, contribute greatly to its strength and endurance.

Law is different than data, sure. But in the context of the Jewish canon law serves the same function as Silver’s formulas serve today. They represent the immutable, the fixed ideas, and are set in contrast to all that is immutable, the ideas in motion. Our history is proof not only that these two categories can coexist, but that they can and do derive their power from one another.

The practice of making meaning from the Torah is split up into two types of writings. There are the halachic ones that deal with matters of law and behavior, and then there are the aggadahic ones that are the more interpretative ones and often appear in the form of a story or commentary that aim to fill in, or illuminate, the many narrative gaps in the bible. Over the years Jewish tradition layered these rabbinic commentaries one upon another rather than determine one more authoritative than the other. This is our system of belief.

In his refutation of Silver’s deification of data, the New Republic’s Wieseltier points out how opinions and ideas in contemporary journalism function in a similar way:

“An opinion with a justification may be described as a belief,” he writes. “The justification that transforms an opinion into a belief may in some instances be empirical, but in many instances, in the morally and philosophically significant instances, it will not be empirical, it will be rational, achieved in the establishment of the truth of concepts or ideas by the methods of argument and the interpretation of experience.”

Wieseltier’s words are very much in tune with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s thoughts on halacha vs. aggadah. Heschel says that aggadah is how we take something as abstract as a law and transform it to make meaning for an individual.

According to Heschel, “Halakhah gives us knowledge; aggadah gives us aspiration. …Halakhah gives us the norms for action; aggadah, the vision of the ends of living. Halakhah prescribes, aggadah suggests; halakhah decrees, aggadah inspires; halakhah is definite; aggadah is allusive.”

And later, as if predicting this very debate: “Halakhah thinks in the category of quantity; aggadah is the category of quality.” As we move to a new moment in journalism, when technology allows us to know more about ourselves through numbers than ever before, let’s remember this and not fall too deep under positivism’s spell. Because forms and patterns will never bring us closer to those ineffable truths than our thinking, feeling, meaning-making minds always have and always will.

Elissa Strauss is a contributing editor to the Forward.