How ‘Klinghoffer’ Stereotypes Both Sides

“Do You Hear the People Sing?” They’re singing a song of their quaint, mysterious religion, and their idyllic homeland. Image by KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA

“The Death of Klinghoffer” is among the most anti-Israel works of art I’ve experienced in recent years. And yet, it’s so intent on crafting a Cowboys-and-Indians story that it reduces its Palestinians to offensive, Orientalist caricatures.

That’s right: This opera isn’t anti-Jewish. It’s anti-Palestinian.

Far too much ink has already been spilled on the question of whether Klinghoffer’s libretto is anti-Semitic. The short answer is no. Its one anti-Semitic diatribe is sung by a villain, and its “Chorus of the Exiled Jews” is more about the mundanity of American Jews going on a pleasure cruise than about Judaism.

But it is wildly anti-Israel, distorting the conflict and presenting only one narrative among many. It’s more agitprop than art.

Yet that Klinghoffer is anti-Israel is not quite my point. There are plenty of good works of art that are anti-Israel, or anti-Occupation. My point is that this one, in both its libretto and its staging, is stupid about it.

Item: Klinghoffer’s hijackers are depicted as generally pious Muslims. They talk about God all the time. In reality, the Palestinian Liberation Front was a Marxist-Leninist faction, and was an offshoot of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, headed by a Christian, George Habash.

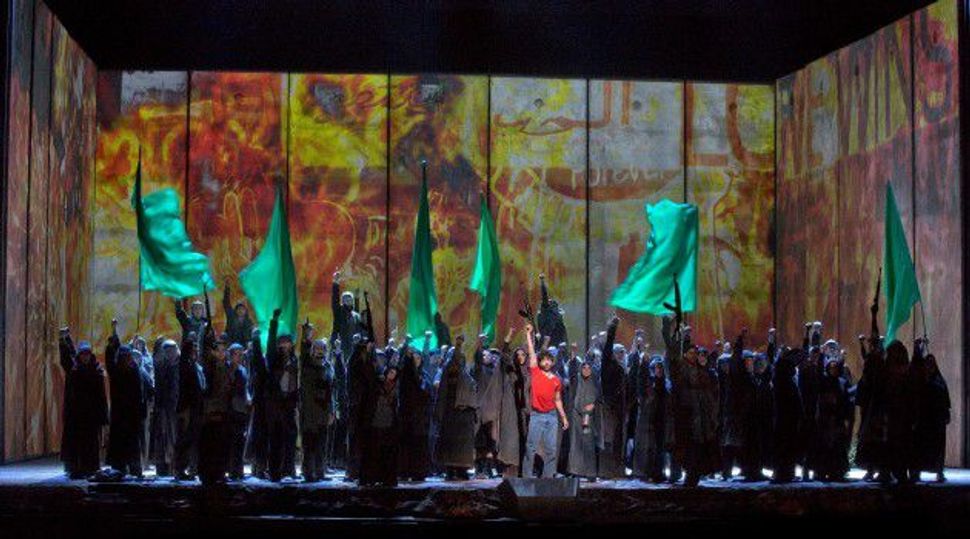

Item: The “exiled Palestinians” are wearing long black chadors and wave green flags. But only a minority of Palestinians are fundamentalist Muslims now, and even fewer were in 1948.

Similarly, one of that chorus’s haunting lines is “Our faith will take the stones he broke/And break his teeth.” Like much of Klinghoffer, this couplet admirably juxtaposes the pain of Palestinian suffering and the shocking violence of (some) Palestinian resistance. It is successfully uncomfortable.

Unfortunately, it is politically stupid. “Our faith”? The Palestinian cause is not a religious jihad, its leadership was not Islamist until the 1990s (and then only partially), and this depiction completely miscasts what is a nationalist struggle.

Religion isn’t the only thing the opera gets wrong. In its new staging, the backdrop is meant to evoke the separation wall, which wasn’t constructed until twenty years after the Achille Lauro hijacking. I get that we’re in some timeless zone of eternal conflict or whatever, but this image is misleading — especially when it is graffitied up at the end of Act One. Whatever the PLF hijackers were concerned with, they were not aware of the separation barrier, the Oslo accords, the second intifada, the first intifada, or the many strands of history necessary to understand the meaning of this image. It’s like putting the Berlin Wall in Cabaret.

The consistent anachronism of “The Death of Klinghoffer” falsely reads 1983 in the light of 2014, and flattens the motives of everyone involved.

Mostly those of the four hijackers. It’s one thing to humanize terrorists; although many of the opera’s protesters apparently view doing so as some kind of treason against the memory of Leon Klinghoffer, humanization and complexification are what good art does.

The problem is that Klinghoffer does the opposite. It romanticizes the hijackers, flattening them into clichés. Here’s the racist thug. Here’s the poet who rhapsodizes about the sunshine. Here’s the kid who’s equal parts music-loving teenager and violent extremist. Here’s the guy who actually has a conscience and prays.

Let’s set aside whether it’s morally objectionable to depict violent criminals in this way. Let’s even set aside whether any of this was based on actual historical fact, which it surely was not. Just on a purely literary level, this is crap. The hijackers are like the Breakfast Club, a collection of stereotypes and clichés.

Which gets to the root of all of these problems: The opera’s reduction of Palestinians to “the Natives.”

On the one side, we have the cosmopolitan, somewhat ridiculous, and banal-in-their-ordinariness Klinghoffers. Leon Klinghoffer’s last earthly words are “I should’ve worn a hat.” This is how most of us live, in America and in Israel. We’re not heroes; we’re tourists. In a sense, “The Death of Klinghoffer” is the poignant death of this banality (and, in the end, Marilyn Klinghoffer’s ability to transcend it).

But on the other side, we have the particularistic, noble, sometimes violent, religious Others. Klinghoffer’s Arabs are like the Indians of a bad Western. They’re proud, they’ve been offended, and while some may be violent, truly theirs is a noble struggle. Cue Kevin Costner, screen left.

Of course, it doesn’t help that the current production stages the Palestinian chorus to look just like the rebels of Les Miserables, another musical which reduced a complicated political reality (and Victor Hugo’s book) to camp. Do you hear the people sing? They’re singing a song of their quaint, mysterious religion, and their idyllic homeland, where no one was turned away from the well in the courtyard.

On one level, this is meant to be pro-Palestinian agitprop, because it’s the Israelis who come and ruin everything. But on another level, it is anti-Palestinian in the extreme, reducing a nation to a series of tropes. And inaccurate tropes at that.

There is something comic about the entire scene, inside and outside of the Met. The airport-like security at the Metropolitan Opera. The ignorant protesters who can’t spell “Al Qaeda” and think that John Adams hates Jews. And inside, a work of great musical beauty (it’s the best Adams piece I’ve heard) and political idiocy that is unlike what anyone — friend or foe — seems to say it is.

A few weeks ago, I met with Harvard Professor Hillel Levine, who was trying to bring some order to this chaos. He was upset by the opera, and upset by the protests. And he told me of his organization (The Center for Reconciliation) and its quest to unite Muslims and Jews in opposition to Klinghoffer, a libretto which, he said, offended both.

At the time, I didn’t think much of this theory. But having seen the opera myself, I think the professor is right.

Where are the secular Palestinians who are trying to fight both Islamism and the Israeli occupation? Why is this tragic incident cast as part of some ancient religious animus between Muslims and Jews — a narrative which plays into the hands of Jewish right-wingers and Islamists alike? How has this libretto managed to be anti-Israel and anti-Palestine at the same time?

There is more anti-Semitism in Wagner’s operas than this one. There is more one-sided politicking in Leon Uris. But considering it’s an opera with such simplistic political ideas, I’ve rarely seen more irony than in the circus that is Klinghoffer.

Jay Michaelson is a contributing editor to the Forward.