Gaza Was Like Home — But I Supported Disengagement Anyway

Image by Getty Images

I first became acquainted with the Jewish settlements of Gaza during my Israeli army service in 2002. This was during the second Intifada and my parents, living in New Jersey and unable to call me due to their deafness, were extremely worried about me. To calm them, when I had a free moment, I’d walk into the nearby settlement of Morag and — in those pre-smartphone days — ask who had an Internet-connected computer at home so I could send my parents an email letting them know that I was okay. I got to know the residents well, and enjoyed many Shabbat meals and even a Passover Seder with them.

Then, in 2005, the Israeli government announced the disengagement plan, calling for the uprooting — by coercion if necessary — of the 8,500 Israeli citizens living in the Gaza Strip. In some cases, these citizens’ families had called the area home for three generations. They were pioneers, settling in desolate areas and establishing thriving communities with the most advanced agriculture, and under many adverse conditions.

The disengagement was not an abstract issue for me: My time in Gush Katif had allowed me to see firsthand the beauty of the area and the wonderful people who lived there.

I admired them.

And I was deeply torn.

Yet, upon further reflection, I became convinced that the plan had to be carried out. I could not see how Israel could maintain its Jewish and democratic character while maintaining control of the Gaza Strip, with its 1.5 million Palestinian inhabitants.

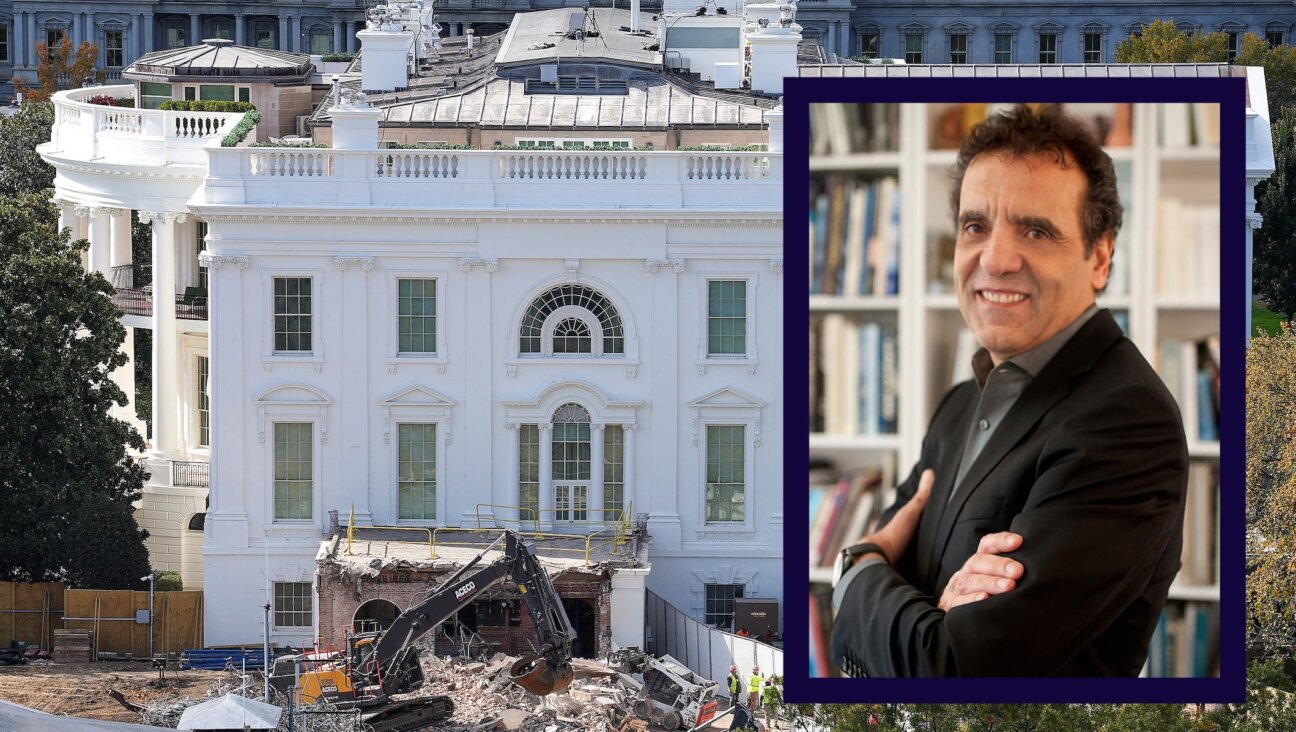

Image by Getty Images

My stance brought me into conflict with many close friends, while simultaneously making me feel unwelcome in my own community. A special prayer against the disengagement plan, with everyone standing in attention and answering “Amen,” was recited in the synagogue I normally attended. While distributing blue and white ribbons in support of the disengagement plan, I was told by some drivers to remove my kippah, since there was no way that a truly observant Jew could support disengagement.

The public discussion over disengagement had turned ugly, with too many using Manichaean terms to frame the discussion. The country was in an uproar. The song “This Was My Home,” originally written before the 1982 Israeli evacuation of Yamit in the Sinai Desert, had been remixed and was topping the radio charts. Initially I resisted the song, because it was one of the anthems of the Gaza anti-disengagement movement. But over time I came to appreciate what it represented. It reminded me that those supporting disengagement should never forget that we were talking about real people, whose homes and entire lives were being uprooted. We could not turn our backs on their raw pain.

So, despite my personal frustrations, I resolved to learn more about the issue. This called for another visit to Gush Katif, this time as a civilian. In January 2005, I spent a Shabbat in the community of Ganei Tal, not in order to argue but to see, listen and learn.

During my visit, one high school student told me that his school was located in Kiryat Arba (near Hebron in the West Bank), and that he generally stayed within this part of Israel — over the Green Line — when traveling from home to school and vice versa. As he spoke I thought of another friend of mine, one who refuses on principle to step foot in Jewish communities located over the Green Line. The two will never meet, I thought to myself, and they will never hear each other’s stories. How can we build a cohesive society if we do not even have the opportunity to meet, much less learn from one another?

Upon returning home, I wrote a letter to my friends:

Disengagement from Gaza is proving to be a heart-wrenching and emotionally draining experience for the people of Israel. As it should be. Having people leave the homes which they painstakingly built, against their will, is not an easy thing to do, neither for the ones doing the removing and certainly not for the ones being removed. Lest anyone think otherwise, the Jewish settlers in Gaza are some of the most committed, talented, and idealistic people in the country and in many ways represent the best of what Israel should be. The fact that something is difficult, though, does not mean that it is not necessary.

Image by Getty Images

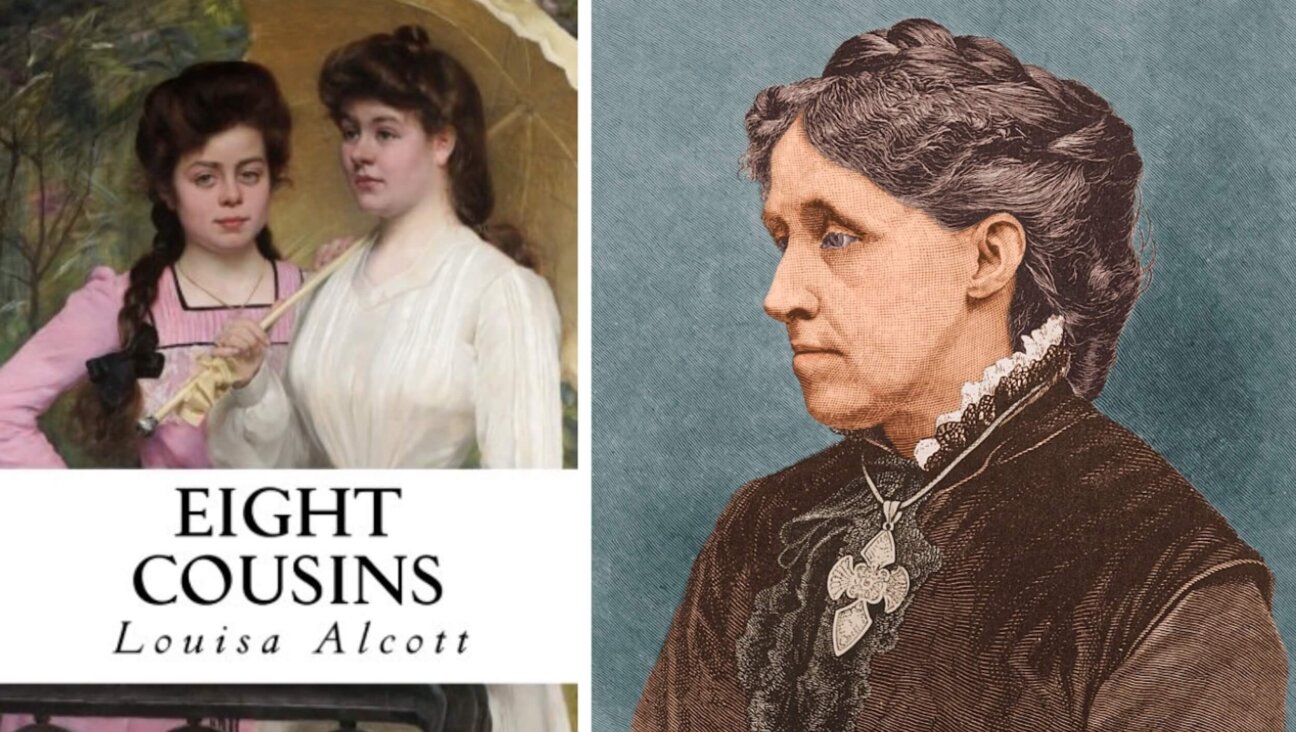

My experiences in the tumultuous year of 2005 left me determined to ensure that Jews with different opinions have the opportunity to engage and learn from one another. I believed that although there are real differences of opinion that should not be glossed over, we can come to appreciate the substantive common ground that unites us. In fact, only by doing this can we constructively confront the issues that do divide us.

Ten years later, I still believe that.

Chaim Landau serves as director of Perspectives Israel, which educates about the complexity of the challenges facing Israel from multiple viewpoints. He is also an associate at Shatil, Israel’s premier social change organization.