After the SCOTUS school prayer decision, what comes next for American Jews?

The ruling walks the line between ensuring all citizens are both free to exercise their faith and free from religious coercion.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

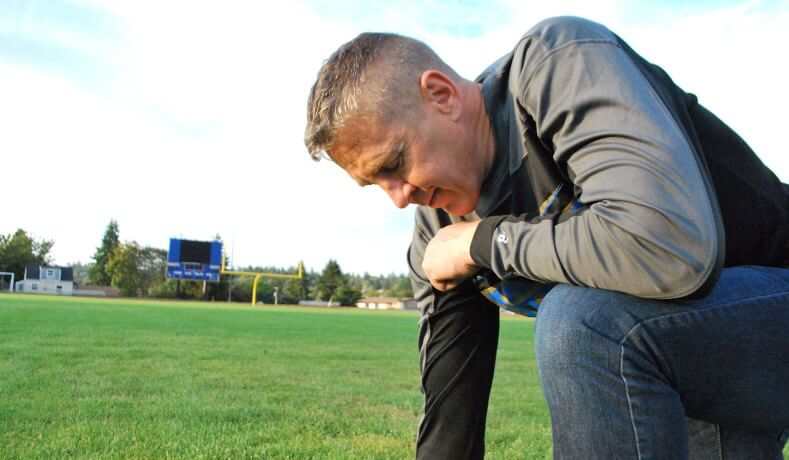

The Supreme Court issued yet another landmark church-state decision on Monday, finding in favor of Coach Joseph Kennedy — a public high school football coach — who had been terminated for praying at the 50-yard line after games.

The case presented not only a convoluted record of when and with whom these prayers took place, but also hinged upon issues of religious liberty, church-state separation and free speech—and has therefore become somewhat of a Rorschach test. To some, the case was all about a coach losing his job for a personal prayer; to others, the case was all about a school district preventing a school employee from indoctrinating students.

Many in the American Jewish community had expressed concern that the decision in favor of the coach might allow public school employees to foist prayers on their students, while others had worried that a decision in favor of the district might prohibit school employees from engaging in religious practices.

Ultimately, the Court’s decision has the potential to protect individual religious liberty while still protecting public school students from religious coercion. Only time will tell whether lower courts will successfully walk that line.

Much of the controversy surrounding the opinion draws from disputes regarding the factual record. This is fairly uncommon for Supreme Court opinions, which typically follow litigation in lower courts that can carefully develop the underlying facts. Still, it seems relatively undisputed that before September of 2015, Coach Kennedy engaged in conduct that was, at a minimum, constitutionally problematic.

The coach would incorporate prayers into his inspirational talks in front of the team and he also led students and staff in prayer on the football field. In September 2015, these behaviors were brought to the attention of the school district, which in turn directed Coach Kennedy to stop these activities because they made it appear as if the school was “endorsing” religion.

It also appears that Coach Kennedy stopped those specific activities when asked to do so, and began saying what he described as a “personal prayer” after the students had begun walking away from the field or were otherwise preoccupied after subsequent games.

On one such occasion, he was joined by students from the opposing team as well as community members; on another occasion, he prayed alone; and on a third occasion, he again prayed and other adults joined him. He did not, however, appear to engage in prayer with his own students after the school district’s directive to the contrary.

Still, the school district terminated Coach Kennedy for continuing in his prayer practice.

From the vantage point of the majority, the fact that Coach Kennedy’s prayers took place while he wasn’t officially on duty — while his “students were otherwise occupied” — led directly to an analysis grounded in religious liberty. Coach Kennedy engaged in a personal prayer, the school district told him that they were adopting a policy specifically targeting religious conduct, and when he refused to comply, the school district terminated him for engaging in that religious exercise. Losing your government job for praying certainly sounds like a religious liberty violation.

But the dissent describes the facts quite differently. In the dissent’s view, Coach Kennedy was praying while very much on duty — “at the center of a school event.” To bolster this point, the dissent even included pictures of Coach Kennedy praying while surrounded by students. These pictures certainly made quite a stir on social media, implying that the majority’s characterization of Coach Kennedy as engaging in private and off-duty prayers was simply false. Indeed, others have characterized the Court’s majority as simply lying.

But that’s not quite right. The pictures certainly show Coach Kennedy praying with students, but from a time period before the school district requested that he cease those activities. Another picture shows him praying with students, but apparently only students from the other team. Should these factual distinctions matter?

This brings us to the second, and maybe most important, feature of this decision. The dissenting justices not only view Coach Kennedy’s prayers as occurring while he was on duty, but they also contend that, as a result, the prayers violated principles of church-state separation. This is for two separate reasons: first, because onlookers would perceive the public school as endorsing religion; and second because, by engaging in prayer while on the job, he would make students feel like they needed to participate to curry favor with him.

But the majority’s opinion dismisses both contentions. On the first count, the majority concluded that interpreting church-state separation as prohibiting conduct that would be perceived as endorsing religion drew from a much-maligned and inconsistently applied constitutional standard — the Lemon test — that had long been criticized by scholars and justices. This test had asked courts to evaluate the constitutionality of government conduct by looking at various factors — the purposes, effects and entanglements of the law — leading to decades of jurisprudential confusion.

Instead, like in several of its recent decisions, the Court interpreted the demands of the First Amendment in light of its history and original meaning. The majority is crystal clear that this includes a prohibition on coercing citizens to participate in government-sponsored religion.

But the majority ultimately concluded, contrary to the dissent, that there were insufficient facts on the record to demonstrate that any students were coerced by Coach Kennedy’s prayers — even subtly. And to the extent some students did express feelings of coercion and pressure in the record, those were either in response to Coach Kennedy’s earlier — and unmodified — prayers, or the complaints were hearsay and therefore insufficient for the majority to change its constitutional calculus. So, without any problems of church-state separation, there simply was no justification for the school district’s unconstitutional termination of Coach Kennedy’s employment.

The extensive debate over the underlying facts is a reminder why the Supreme Court typically takes cases with a clearly developed factual record. The clash over who participated in which prayer has generated more finger-pointing than illumination. But, for a Jewish community deeply concerned both about coercion at the hands of a religious majority and about religious freedom to engage in often unpopular religious practices, where does this leave us?

Prohibiting government endorsement of religion provides important protections, especially for a religious minority like the Jewish community, and especially in the context of public schools. Now, when evaluating potential violations of church-state separation, the Court will focus not on perceptions of endorsement, but more narrowly on whether the government is coercing religious conduct.

If those protections are to be adequate for American Jews, the Court will likely need to have a wide view of what constitutes coercion — a particularly thorny concept in the context of public education. In turn, lower courts will need to police government institutions for subtle and informal methods of coercion.

At the same time, it is important not to lose sight of how the Court’s decision provides important protections with respect to religious liberty. If the government could recharacterize private religious exercise as the conduct of the state—and then prohibit it as an unconstitutional merger of church and state—then religious government employees, and in particular those of minority faiths, could all-too easily have their religious activity suppressed.

Yesterday’s opinion, in surgically carving a private space for Coach Kennedy — amid the chaos of a high school football game — certainly provided guidelines that will protect Jewish government employees in environments that might be less than hospitable to their religious practices.

All told, the regime ushered in by the Court’s decision provides a framework capable of ensuring that all citizens—whether government employees or public-school students—remain both free to exercise their faith and free from religious coercion. It will be up to lower courts, implementing this framework in the coming years, to fulfill that promise.