Is having a Jewish state worth it? A new book makes the case for optimism

75 years after Israel’s founding, Daniel Gordis takes a hard look at the country’s past and future

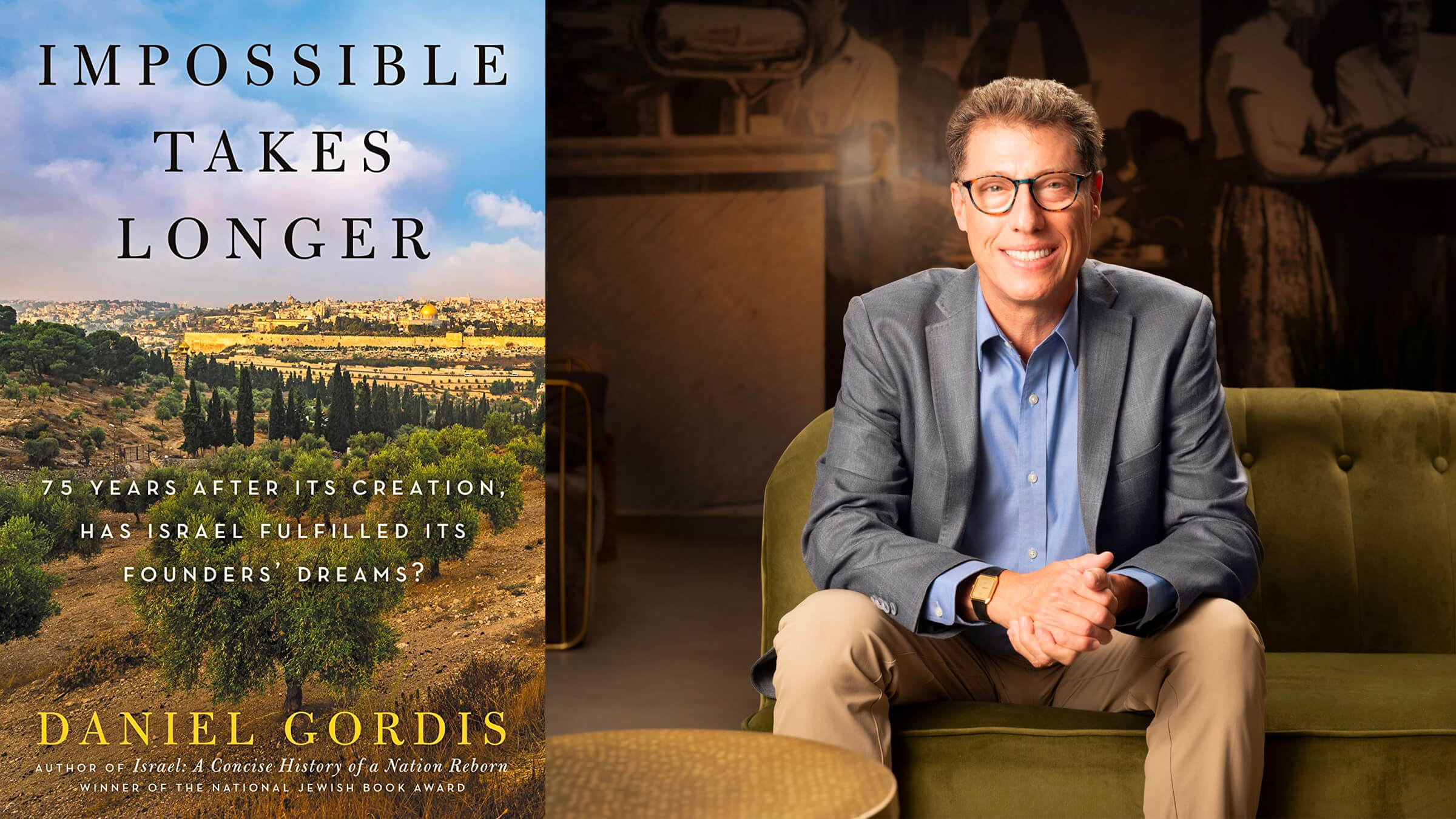

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Celebrating Israel’s 75th birthday this year feels a bit like popping open a bottle of Champagne at the scene of a car crash.

Three sets of Jewish siblings have been murdered in as many months by Palestinian terrorists; the earth is still fresh on the latest victims’ graves. Extremist Jews committed a shameful pogrom in the Palestinian town of Hawara in February, and violence in the West Bank is only getting worse. And Israel has barely survived the greatest challenge to its democracy since the founding of the state, bringing nearly a quarter of a million Israelis into the streets to protest the proposed judicial overhaul.

As Israeli author Daniel Gordis reminds us in the introduction of his new book Impossible Takes Longer: 75 Years After Its Creation, Has Israel Fulfilled Its Founders’ Dreams?, which was published on April 11, this is the longest the Jewish people have maintained sovereignty in their own state. On the worst days of violence and bloodshed, I admit that I wonder if it’s been worth it.

But despite all of the pain, upheaval and uncertainty, there is much to be grateful for.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

As Gordis argues, Israel has fundamentally changed the Jewish condition in extraordinary ways. That alone, despite Israel’s many challenges, should provide a case for optimism.

This interview was conducted on March 29, 2023. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Why should American Jews be bothered to care about what’s happening in Israel right now?

Maybe they shouldn’t. I mean that really quite seriously.

Our issues are very real. And to me, they’re very painful. But here’s why I would hope that an American Jew and an Israeli Jew would each care about each other.

Israel is more meaningful as the nation-state of the Jewish people than as the nation-state of its citizens. The purpose of the state was to breathe new life into the Jewish people. And I think Israel has transformed the existential condition of what it means to be a Jew.

We can’t stop people from killing Jews. But in Israel, they can no longer kill us with impunity. American Jews are beneficiaries of that reality, even with all of their very legitimate angst about all sorts of really complicated, painful issues.

Israel is one of the last sources of passion — even anger — in a way that few other things are. What else are American Jews going to get worked up about in the Jewish world? Tikkun olam? That is not a source of passion for most people, and it’s also not distinctly Jewish — thank God we don’t have a monopoly on doing good things in the world.

But ironically, changing the existential condition of the Jewish people has enabled American Jews to lean more into the universal values of Judaism and less into the particularist aspects. You ask, “What are American Jews getting worked up about if not Israel?” And the answer is abortion access, and immigration, and domestic political concerns that they see as fundamentally Jewish.

What about the Jewish tradition informs these positions?

The vast majority of American Jews assert that their liberal politics — and I’m not saying that derisively in any way whatsoever, my politics are liberal also — are their Judaism. But then the whole Democratic Party is Jewish. And that doesn’t really mean very much.

We are not in the business only of staying alive. We’re in the business of staying alive as a Jewish state

When global Jewry doesn’t agree on which Jewish values take precedence, how do you go about determining the future of Israel, this ethnic democracy that is supposed to be upholding Jewish particularism? Internally within Israeli society, it’s an open question as well.

There’s a certain amount of humility that each side needs when it looks at the other. And I think humility has been in very short supply.

When Israeli politicians blab about American Jewish assimilation, I understand it. But why don’t you actually learn something about the challenges that these women and men were up against in leading American Jewish communities before you opine?

And I would say the same thing to the other side. You don’t like the sight — neither do I — of Israeli jets pounding Gaza while the Iron Dome shoots down the stuff that’s headed at us.

But before American Jews opine, ask yourself, why is the progressive political party Meretz in exactly the same place that Netanyahu’s Likud party is on this? To what extent have you, living in the almost idyllic setting of America, actually allowed your self-preservation to atrophy because you haven’t had to hone it all this time?

So, your view is that American Jews don’t understand that the question of basic survival still deeply motivates a lot of day-to-day decisions in Israel.

It’s the security issue. But it’s also the particularism issue.

I want Israeli Arabs to have every single civil right that I have. Having said that, I want to figure out a way of doing that in a country in which it is totally obvious that the purpose of this country is the preservation of the Jewish people. We are not in the business only of staying alive. We’re in the business of staying alive as a Jewish state. It’s always going to be a delicate dance.

The easiest thing to do conceptually, not morally, is just, “Goodbye. There’s going to be an Arab state now. All of you go over there.”

I actually think that would be a terrible thing. Not only because it’s totally unfair to these human beings, but because I think we’re challenged and enriched in a way that we have to ask ourselves, how does the majority protect the rights of the minority? And how do we as Jews also make space for non-Jews in a way that many non-Jewish societies never made space for us? How do we take our own experience and do better?

There are moments when it’s going to be easier and when it’s going to be harder, but you say, “I’m invested in the relationship.”

There are going to be days you are going to think that what I just said is wrong, and immoral, or too particularist. But there was a goal here in Israel, about changing and creating a new Jew. And oh my God, look how successful it’s been. It’s been so successful, it’s a little hard for me to remember what those old Jews were like.

How do you deal with internal threats to Israel that stem from our religious tradition?

One of the first weeks that we had protests, it was a really cold night in Jerusalem. So I put on my coat, I put on my little wool hat. When we got to the protest, my wife said, “Take off your hat.”

I was like, “It’s freezing. Why?”

And she said, “because people need to see kippot here.”

She wanted people to see that there are people who happen to be personally observant, whatever that even means, and who care deeply about the plurality and the pluralism and the democracy and the liberalism of Israeli society. Because we’re so worried that so many of us aren’t like that.

You’ve long been critical of non-Israelis who strongly criticize the Israeli government. And then in February, you co-wrote a letter in The Times of Israel about how intervention and speaking up is now necessary. What led you to that place?

I really don’t have a problem with American Jews who are going to criticize Israel during the next round of violence who say, “I understand that Israeli kids are sleeping in bomb shelters. But I still have a problem with Israel bombing Gaza.”

I don’t agree, necessarily. But I would feel like I was heard, like my grandchildren were factored into your calculus. And if, God forbid, something bad happens here, then I want to know that you’re crying, too.

We need each other for a robust conversation about the kind of Jews and the kind of human beings we want to be instead of dissing each other all the time and complaining about how either right-wing or assimilated we are.

The letter was meant to provide support for people who are on the inside of the leadership of some pretty pivotal American Jewish organizations who were hesitant to get involved in Israel’s domestic issues.

I didn’t have any illusion that Netanyahu was going to care about any of those organizations. But I was trying to get to a critical mass where Bibi would say, “This is bad. Maybe I should pull back on the throttle a little bit.”

How do you hope Israel emerges from this judicial reform crisis? And what are the more negative possibilities?

There was a huge political awakening for a lot of people who deeply cared about this country. The most law-abiding sector of Israeli society went out to protest, week after week after week.

Some of the right-wing issues are just going to get uglier and more fanatical and more nationalistic, and Israel has a tremendous reckoning to do. The hatreds which are so deeply imbued in this country could blow up. Religious leaders, educational leaders and political leaders really need to take the high road and to see it as their life’s goal to address this.

I hope the 180,000-plus people who were protesting are asking themselves, “What are we going to do over the next five years to make sure we don’t go back to this place?”

I mean, if you really want to go wild, you could imagine a constitution. That may be a little bit optimistic, but I don’t think that it’s crazy optimistic. I think people are recognizing just how bad it is not to have a constitution.

You open the book very starkly by reminding readers that previous iterations of Israel never maintained Jewish sovereignty for longer than 74 years at a time. What has to change within Israel for it to endure this time around?

I think we need to be united by a sense of common purpose.

To be quite honest, the radical secular Tel Aviv left — who are great people, and the ones that just saved Israeli democracy — need to be able to ask themselves, “How much Jewish content needs to be in my house so that my children will have something to discuss with religious Jewish children?”

And Haredim should likewise ask themselves, “Do I really want the Minister of Finance to be a person who has literally never read John Locke or Alexis de Tocqueville, or the Federalist Papers, or even seen Hamilton?”

What does each side need to do to make itself more robust intellectually and morally? Those are the questions that we have to ask.

And we ought to learn our history. Israel enduring as a united state with Jewish sovereignty for 73 years the first time around, and 74 years the second time, should send shivers up your spine. I mean, it should really make you not able to fall asleep.

I think we dodged disaster this time. But it ain’t over. We have a huge responsibility not just to our children and grandchildren, but to the Jewish people writ large, not to screw this up.