The Israeli Dee family lost three members during Passover. Why won’t they sit shiva until after the holiday?

In Jewish law, mourning and festivals do not mix

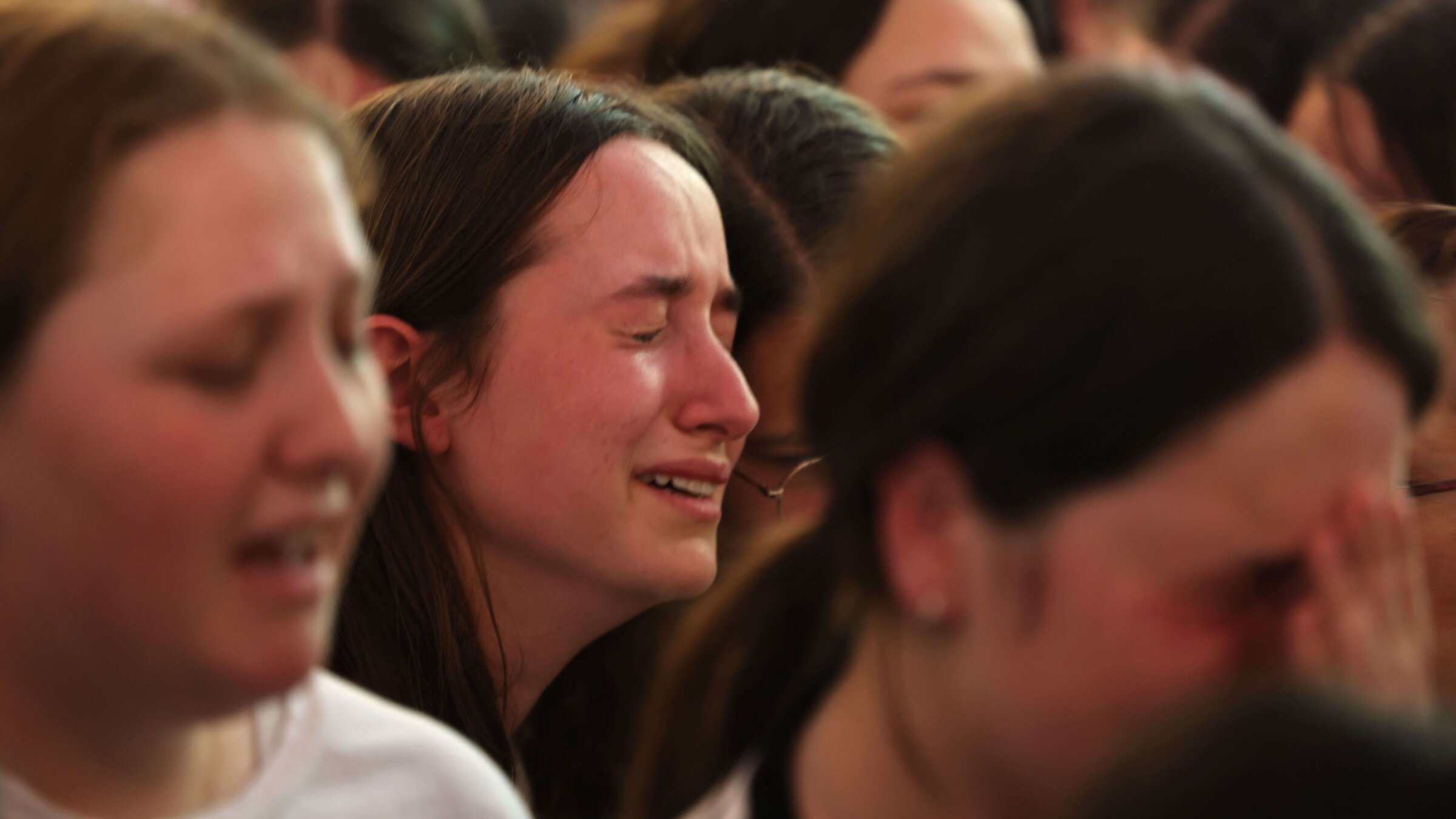

Mourners react during the funeral of British-Israeli sisters Rina and Maya Dee at the Kfar Etzion settlement cemetery in the occupied West Bank, on April 9, 2023. Photo by Menahem Kahana/AFP via Getty Images

This Passover, Israelis and Zionists the world over have experienced a range of emotions.

During the festival, several innocent Israelis were murdered by Palestinian terrorists. Some of us were able to easily compartmentalize and move on from the news of the attacks. Others were stymied by the frustration, sadness and anger of it all. It is difficult to celebrate a festival while attending funerals and reading constant updates about the victims.

Jewish festivals are often mocked as events that we commemorate in the following way: “The non-Jews tried to kill us, God saved us, we survived, let’s eat!”

Like most humor, there is truth to the joke. Jewish history is a rollercoaster of highs and lows.

I learned about a related aspect of Jewish law when I was only ten years old. During Passover, my paternal grandfather passed away. My grandmother had passed away just six weeks before, so I was familiar with the mourning process: I knew that my father would once again have to “sit shiva” after the funeral and burial.

But because my grandfather had passed in the middle of a festival, when we’re commanded to be happy, my father’s mourning would be delayed. While my grandfather’s body would be buried immediately, my father wouldn’t start shiva until after Pesach, when the commandment to be happy ended. According to halacha, the happiness of the festival and the mourning of loved ones are mutually exclusive.

This halacha is playing out in real-time this Passover on a national level. Rina, Maia, and Lucy Dee, the sisters and mother killed during Passover, were buried during the festival. But their loved ones won’t sit shiva for them until after the festival concludes.

The halacha of suspending mourning doesn’t only apply to the family of those brutally killed, but to the nation as well. It was challenging for Israelis to recognize that, as hard as it might have been, they couldn’t allow their feelings of the attacks to overcome their happiness and celebration of the festival of Passover.

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, who himself passed away 30 years ago during Passover, reportedly characterized putting aside the raw feelings of mourning for the happiness of the festival as the toughest commandment in the Torah.

This is not the first time we’ve lived through this. At the very start of Passover in 2002, a Palestinian suicide bomber walked into the Park Hotel in Netanya during the Seder and detonated an explosive vest, killing 30 civilians and injuring over 140.

It was the deadliest attack Israel had suffered in years, and the holiday was marred by the ensuing operation in Jenin and other Palestinian villages, which resulted in the loss of more lives.

I think back to that Passover this year. In a way, these Passovers are much like the original Passover. Our rabbis taught us that only one-fifth of the Jewish people left Egypt during the Exodus, the rest having died during the plague of darkness.

That first Passover, the Jews must have also held a mix of emotions, ecstatic that they were freed, while acutely aware of their losses.

Jewish scholars often teach that Passover was the seminal event that formed Abraham, Isaac and Jacob’s descendants into a people, and its celebration hearkens the Jewish people back to its roots each year. Passover reminds the Jewish people of the fundamental Jewish condition of constantly balancing celebration and mourning.

To contact the author, email [email protected].