Is Midge Maisel my modern Orthodox neighbor?

The last season of ‘Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’ includes much needed observant Jewish visibility

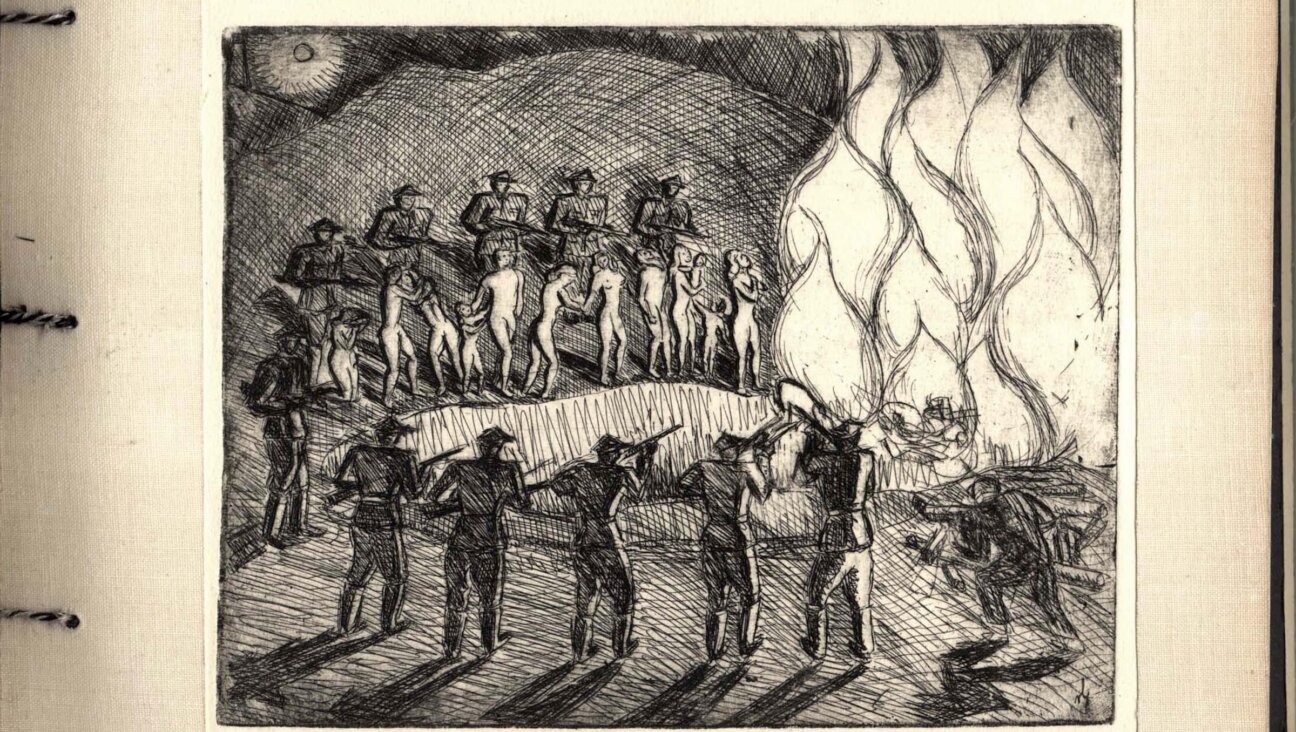

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I was first introduced to the The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel series via a non-Jewish academic peer who informed me that the show was, in her words, “extremely Jewish.”

Intrigued by my colleague’s certainty of the level of Jewish content throughout the series, as well as the idea of a 1950s Jewish housewife trying to make a career out of standup comedy in New York City, I began watching Maisel after the second season had been released, in late 2018. It didn’t take long in my binge-watching marathon to see that The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel was very entertaining. It also became clear that the series was not very similar to my Jewish experience, due to the show’s lack of exposure to Orthodox Jewish life.

Only in its fifth and final season, which aired a three-part premiere the day after Passover and will continue to release episodes until the end of May, does the viewer finally catch a glimpse of a social and cultural Jewish identity that also involves strict halachic practice. Though this display is a long time coming, I’m genuinely pleased. The last season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel finally portrays an observant Jewish lifestyle in a way that does not fetishize Orthodoxy, but honors it.

In episode six of the latest season, the presence of observant Jews is front and center. While Midge Maisel’s rabbi-in-training son Ethan and new Israeli daughter-in-law Chava bow and sway in fervent prayer inside a New York City synagogue, a 40-something Mrs. Maisel leans over to her ex-husband to ask for reassurance. “Does Chava scare you, too?” Midge asks Joel Maisel. When Joel appears confused, Midge elaborates. “Corporal Chava, does she scare the shit out of you? ‘Cause I think one of these days you’re gonna find my body in a date tree.”

When the scene erupts into chaos, just a moment later, the Israeli Chava seems unsurprised and flippantly asks her husband Ethan, dressed in white yarmulke and a full tallis, “What has your godless mother done now?” Turning quickly, in her bright suit and the matching red beret which sits upon a short wavy wig, Midge addresses her daughter in-law head on. “Damn it, Chava, I know a decent amount of Hebrew.”

It’s a quirky bit that breaks some of the tension in the scene, but this segment is unlike many others, in that it provides a portrayal of a life and culture often hidden from the Maisel world: the norms of the observant Jewish community.

It’s a divergence from the earlier seasons, which, while taking place in New York City of the late 1950s and early 1960s, does not expose the viewer to the Eastern European, still unacculturated Jewish observant lifestyle. Though Midge’s family enjoys a Yom Kippur break fast and a summer trip to the Catskills, they are undoubtedly secular Jews who likely lived in the United States for several generations before the show’s plot takes place. Others in the Maisel world are cut from a similar cloth — longtime assimilated Jewish families with very strong cultural identities and consistent annual rituals who do not significantly alter their lives based on halachic practice.

While I could understand my colleague’s sense that the series depicted something genuinely Jewish, the lack of exposure to Orthodox Judaism was striking. Orthodox Jews, and other Jewish individuals who retained halachic observance during this time, would not likely have been as invisible to Midge’s family in the first four seasons as series creator Amy Sherman-Palladino depicts. The thousands of new immigrants who came to New York City in the years after the Holocaust and who remained steadfast in their observance of halachic rituals were not only significant in numbers, but had a large ripple effect on the American Jewish population. In fact, many non-observant Jews helped these individuals to access resettlement services, new jobs and non-interest loans. These observant Jewish individuals would certainly have been worthy of at least a small scene or a background image, but were ignored in the early seasons of Maisel. The series did not seem too keen to introduce these individuals or integrate their stories with Midge’s excursions into other foreign worlds.

The shift in the final season, toward providing a glimpse into Orthodox life, is therefore surprising and welcome. In a series of flash-forward episodes, we meet the once-young Miriam Maisel who is now a middle-aged woman who wears wigs, visits Israel and has a son who is training to be an Orthodox rabbi. This Mrs. Maisel still enjoys off-color humor and discussing the many sexual relationships she’s had with famous men. But she also appears to be deeply drawn to and in a strong relationship with her now-religious son.

The change from a series in which the Maisels and their friends and family have almost zero interactions with observant Jews, to one that tells Midge’s aging story through her promoting wigs, standing next to her son in his tallis, and mastering the language of the Jewish state, a place that is rarely mentioned in earlier seasons, is a fascinating tale of a family whose child found their way to a more observant lifestyle and seemingly brought his parents along. It’s not an unfamiliar story within modern Jewish history, where the ba’al teshuva movement shifted the trajectory of thousands of families.

Had The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel promoted visibility of observant Jews in earlier seasons, the point of interaction for the Weissman-Maisel clan likely would have been volunteer efforts, a donation of some sort, or a nod from across the street. In placing observant Judaism right into Midge’s home, the series has now magnified this experience rather than simply adding it in as texture. In making observant life so fundamentally close to Midge and Joel, Sherman-Palladino has reduced its alien nature, making religious practice and Orthodoxy incredibly normal and nonchalant, in the viewers’ eyes.

Nothing about Midge has fundamentally changed while her son has become religious, even while everything has. And that is the power of visibility in cinema. A Marvelous Mrs. Maisel in which the “extremely Jewish” practices are depicted as archaic and uncomfortable is not a show that depicts Orthodoxy, but rather a show that others it. In finally revealing a slice of the Jewish community through a perspective that enhances its closeness to Midge’s storyline, the viewer’s sense of Orthodoxy is not outdated and fetishized but an accurate portrayal of observant life: different and yet, all the same.

With only a few episodes left in the final season, I wonder if we’ll find that Midge’s final decades are spent as a modern Orthodox stalwart of her community. It’s the story of thousands of Jewish women like Midge, and it deserves a beautiful telling with a fabulous hat to match.

To contact the author, email [email protected].