Tearing down posters of Israeli hostages isn’t resistance — it just shows you can’t handle complex grief

The Israel-Hamas war is making clear that many people cannot hold space for the suffering of two peoples

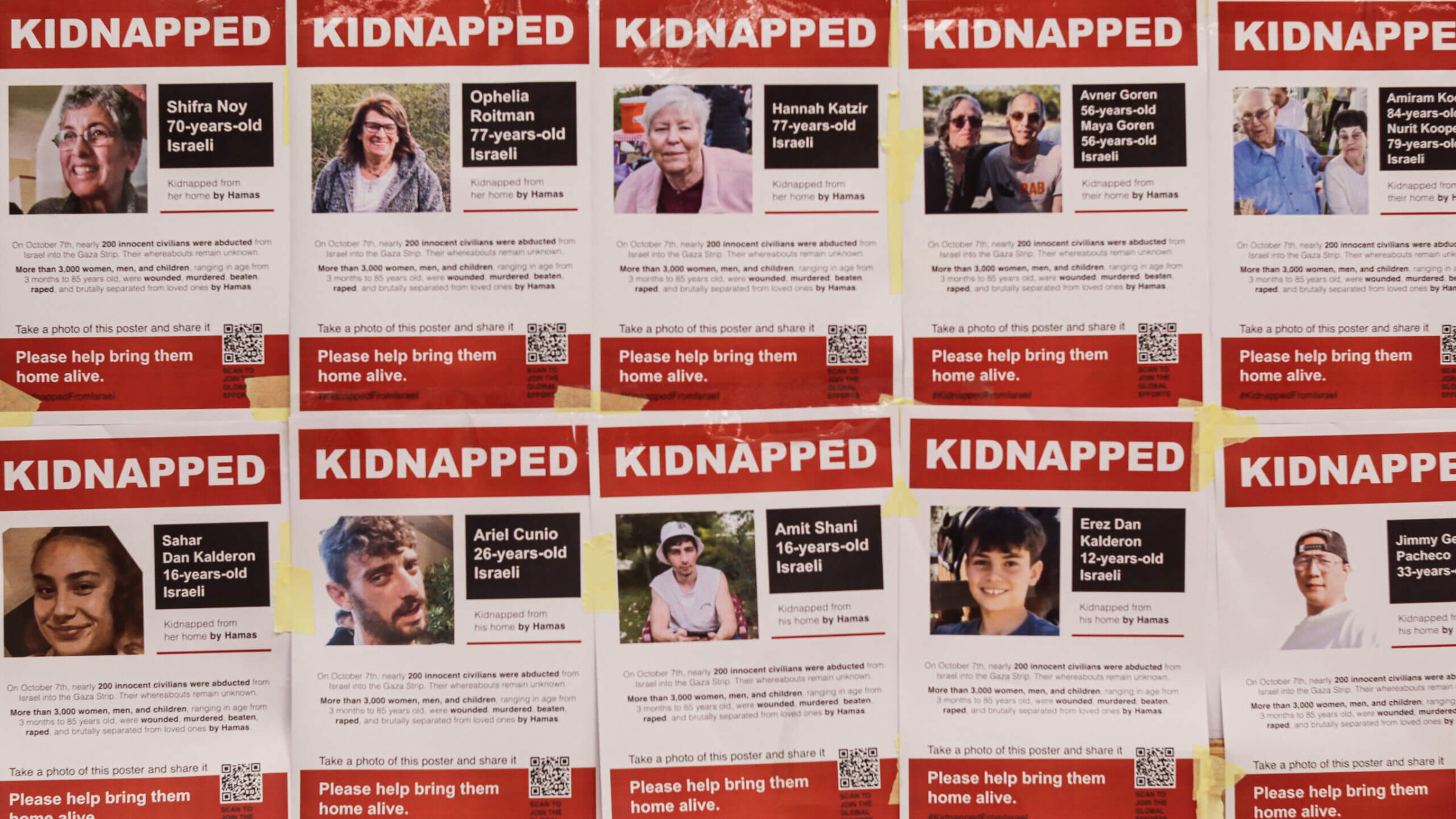

Posters showing the faces of Israeli citizens kidnapped by Hamas militants on the wall of a media office in Sderot, southern Israel, on Tuesday, Oct. 17, 2023. Photo by Jonathan Alpeyrie/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The smiling face of Kfir Bibas, just 10 months old, was ripped in half. The poster that bore his image had been torn, leaving only the top of his red hair and the left crinkle of his smile intact. The bold white text at the top, “KIDNAPPED,” was also ripped, leaving only the partial word “KID.”

Over 200 Israelis were taken hostage by Hamas terrorists on Oct. 7. Just four have been released. To raise visibility for their plight, posters with a white background and lined in red share each hostage’s image, name, age and nationality. They have been placed around cities globally. And incomprehensibly, there is also a popular campaign to deface and tear them down.

The posters contain no political affiliation or message of endorsement for the Israeli government. They do not advertise a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, nor do they advocate for the continued bombardment of Gaza. And yet their existence has become yet another tool in the highly toxic, weaponized cesspool that is the social discourse around the Israel-Hamas war. It painfully occurs to me that, if I were killed by Hamas while visiting my family in Israel, my murder, too, would likely be excused away.

A simple message

A brief paragraph on the posters explains that “nearly 200 innocent civilians were abducted from Israel into the Gaza Strip,” and that thousands ranging in age from 3 months to 85 years old were “wounded, murdered, beaten, raped and brutally separated from loves ones by Hamas.” There is a QR code and a plea to take an image of the poster and share it widely. Large text on the bottom reads: “Please help bring them home alive.”

The message is unimpeachable. I remain horrified that a simple plea to witness Israeli suffering and to help bring an innocent baby home safely after a violent kidnapping is controversial.

Yet even the White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre avoided answering questions about whether tearing down the posters was a peaceful act of protest or should be condemned, before ultimately saying on X that tearing them down was “wrong and hurtful.”

The entire poster debacle — and the ensuing campaign to document, shame and, in some cases, dox those who tear them down — raise profoundly important questions about the nature of public grief and mourning. If nothing else, the war, and the hostage posters’ destruction, has shown me that our society does not believe that we can grieve for two peoples at the same time.

Two peoples’ suffering

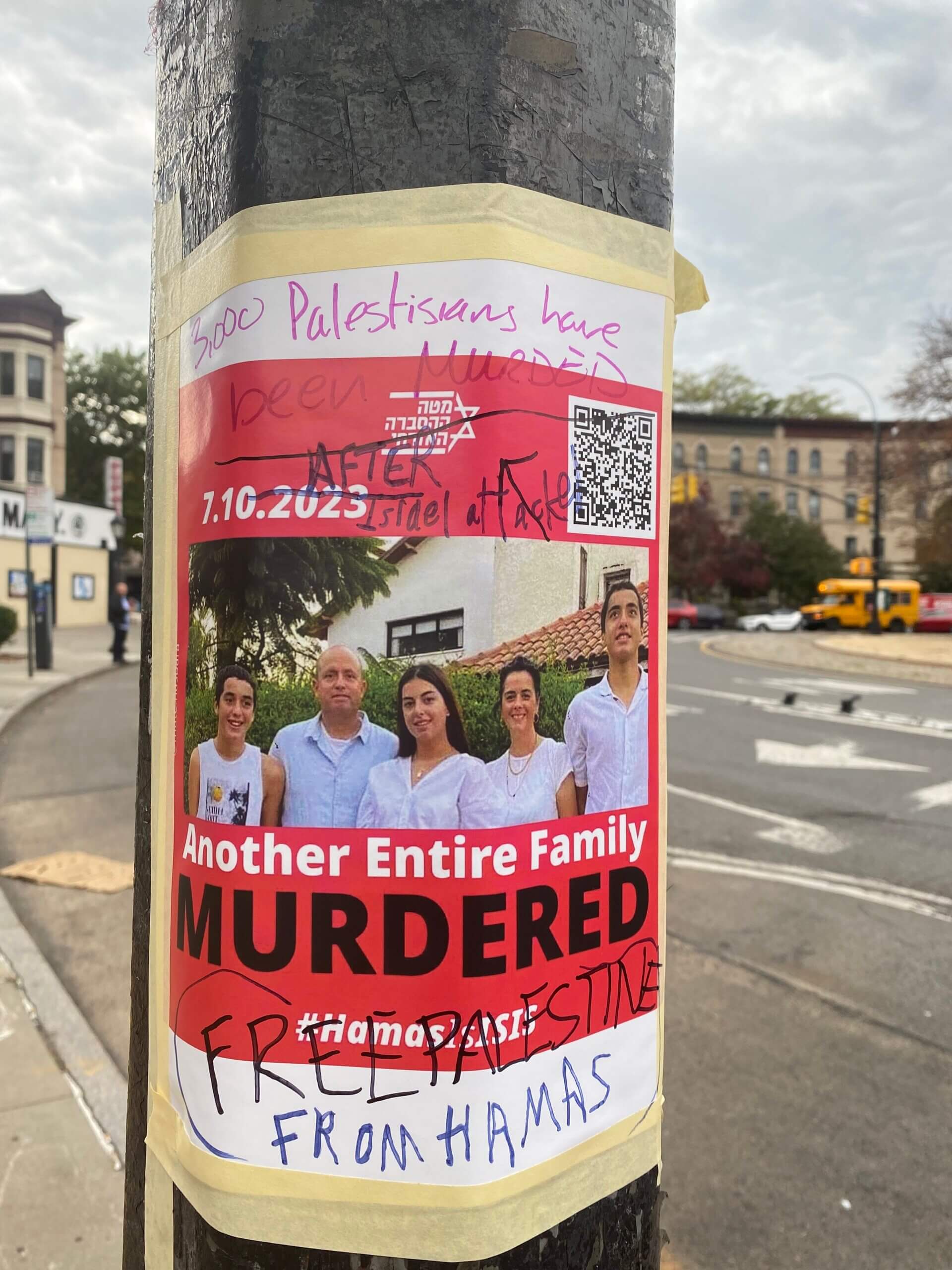

Eleven days after “Black Shabbat,” I saw a poster of the Kutz family in my Brooklyn neighborhood, glued to a traffic signpost near the entrance of Prospect Park. Aviv, 54, Livnat, 49, Rotem, 19, Yonatan, 17, and Yiftach, 15, were found murdered in a single bed in their home in Kfar Aza, clutching each other in a final embrace.

The poster was marked with graffiti: “3,000 Palestinians have been MURDERED.”

Someone else had drawn an arrow to this statement with the addition: “AFTER Israel attacked.” Another had written “FREE PALESTINE,” and below that yet another person: “FROM HAMAS.”

All of these statements were in different colored-markers, indicating at least four different people felt the need to qualify or justify the massacre of an entire family.

None of the statements scrawled on the poster were necessarily objectionable or inaccurate. It is undeniable that civilians in Gaza are dying by the thousands from Israeli airstrikes. It is also undeniable that Hamas has oppressed and brutalized Gazans for years, placing them under a communications blockade and suppressing any mention of dissent.

Yet the very visibility of Israeli civilians murdered by Hamas seems, for many, to negate or erase Palestinian suffering. This particular poster was obviously intolerable to certain individuals, who felt that taking even a moment to witness one person’s suffering canceled out any other person’s suffering.

This mentality was echoed recently when a New York City public defender, Victoria Ruiz, was doxxed, threatened and ultimately resigned after she was captured on video removing hostage posters while attending a vigil to mourn Palestinians killed over the last month. The video clearly shows her removing the red-banded hostage posters, but Ruiz has asserted that she was removing a poster with “handwritten” statements on it “justifying the bombing of Palestinian civilians.”

One person coming to her defense on Twitter argued that while the actions of Hamas were “an inexcusable act of horrible violence,” the hostage posters are “thousands of miles away from Israel and Gaza, use the lives of the missing to justify the ongoing genocide in Gaza.” They went on to argue that “removing a poster is not a crime.”

What Hamas did to civilians was an inexcusable act of horrible violence.

— joseph osmundson (all pronouns) (@reluctantlyjoe) November 6, 2023

What Israel now does in response is genocide, as they have the ability to displace millions and kill tens of thousands for the crime of where they were born.

Removing a poster is not a crime. Genocide is.

In New York City, posting signs on public property like a lamp post or building is technically illegal. But to argue that the presence of these hostage posters, which do nothing but call for the hostages’ safe return, and the very lives of the hostages that they represent, are solely a political tool indicates a profound moral rot. Tearing them down is not an act of physical violence, but complete callousness toward human life and suffering.

I do not believe that doxxing those who remove the posters is the answer. But I can understand the desire for accountability from those who deface photos of innocent civilians held hostage by a fundamentalist regime. Publicly shaming the individuals caught on camera satisfies a temporary urge for vengeance that ultimately benefits no one. Even the argument that antisemites deserve to be outed for this behavior is not one that I’m sure holds water. How are we ultimately served by knowing who the Jew-haters are?

The tent for global grief right now is vast. Civilians are dying in Sudan, Ukraine, Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. If we cannot dwell in that tent together and acknowledge one another’s pain, then I fear we are truly beyond hope.

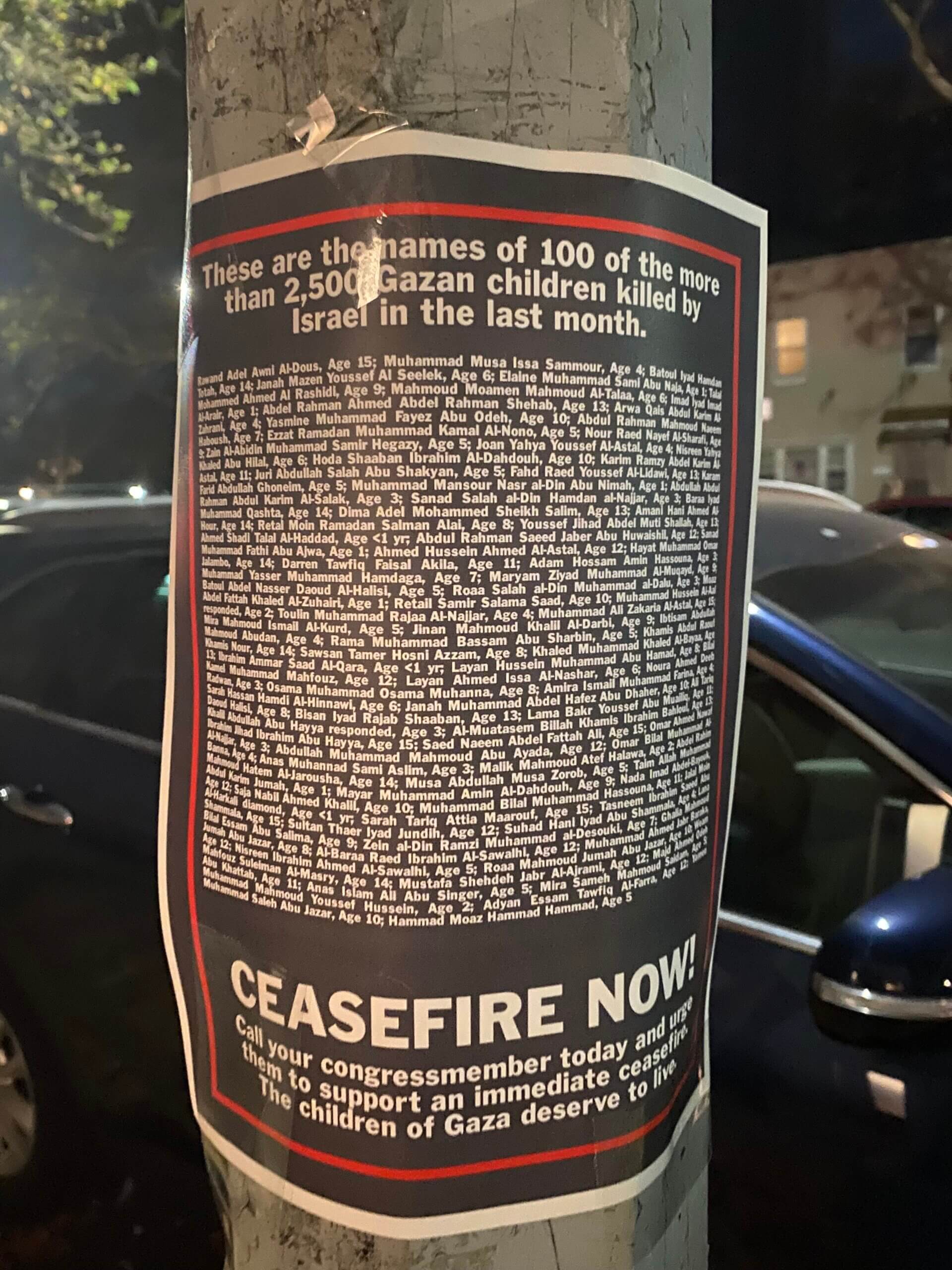

I’ve recently started seeing another poster accompanying those of the hostages. Rimmed in a red band, the white text lists names of 100 Gazan children who died from Israeli bombardment. It calls for a cease-fire: “The children of Gaza deserve to live.”

Sadly, I have seen these posters being ripped down as well. But their presence seems to me to be the best way of grappling with the unimaginable suffering on both sides of this war. Palestinian suffering does not negate Israeli pain, but emphasizes our moral obligation to pursue peace in this region at any cost.

Both the Talmud and the Quran teach that anyone who destroys one soul carries the blame for having destroyed an entire world. The many thousands of worlds, Palestinian and Israeli, that have been lost in this interminable month break my heart constantly. This shared teaching does not end with worlds destroyed, however, but continues with its inverse: Those who save one soul are saving an entire world.

Our suffering and our joy are inextricably intertwined. Only when we begin to understand this will there be any hope for the future of the Holy Land.

Editor’s note: This version of the story has been updated to show that Victoria Ruiz said she was removing a poster with “handwritten” statements on it, and not a separate handwritten flyer.