In the campus protests, Jews got outorganized

Liberal Zionists in the U.S. must learn from student protesters in order to rebuild collective power

Pro-Palestinian protestors gather after police cleared a new encampment of on the University of California, Los Angeles campus in 2024. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

As a proud American Zionist who would be pleased to see my children serve in the Israel Defense Forces, I’ve been shocked by some of the wild claims of the campus protesters, including those that Israel is engaged in genocide. I have watched as well-meaning students espouse hateful ideas as truth. But I am not surprised. As a longtime labor organizer, I know the results of good organizing when I see it. Game respects game, and I have to say: The campus radicals have game.

What they won was not a media victory, or a propaganda victory, but an organizing victory. And now, liberal Zionists have to learn from them.

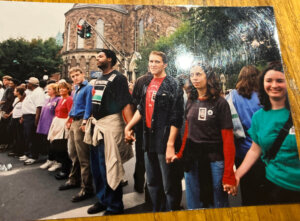

With decades of experience as a labor organizer, I can see that as a Jewish community, we largely stopped organizing with the left 50 years ago. Conversely, the Palestine movement has strategically and painstakingly built relationships with other activists. Indeed, the first time I got arrested as a union organizer 25 years ago, the guy holding my hand was wearing a “Free Palestine” T-shirt. The pro-Palestine movement as it exists today is, in part, the result of years of careful coalition building including Occupy Wall Street, Ferguson, the Women’s March and Black Lives Matter.

As Jews, however, our activist muscles have atrophied. We made a tactical decision long ago to work inside the system.

Organizing means exercising political power by getting large numbers of people to act in a coordinated fashion. It’s part art and part science. I learned to organize from labor activists in the Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union (now called UNITE HERE) when I joined the anti-sweatshop movement as a student at Yale in the 1990s. Those union leaders taught us how to build a movement by learning how to have powerful one-on-one conversations with our peers. We learned to listen to those we disagreed with without being defensive, and how to build trust over time. Slowly, they told us, we could change minds.

At first, I was awful at it. It went against all my instincts as a college student to debate or offer evidence in order to win an argument. I thought if I could only prove to people the error of their ways, surely they would join me. I learned the hard way that winning arguments moved very few people. Gradually, I learned how to listen and inspire participation instead.

After hundreds of conversations, my peers and I got some traction and we began to stage small and then bigger protests. When our demands to stop manufacturing university apparel under sweatshop conditions were not met, we got angrier and more radical. Eventually we built an encampment in front of the college president’s office and stayed there for weeks. After a lot of rain and sleepless nights, we lost: The administration did not meet our demands.

Following that stinging defeat, I started working full time in the labor movement, promising myself I would learn to be a better organizer. Over the next several years, I had thousands of one-on-one conversations, mostly in Spanish, with hotel workers, hospital workers, cafeteria staff and other people in the service industry fighting for better wages, safer working conditions and health care coverage. I participated in strikes and led some small job actions and got arrested many times. Most importantly, I learned what it took to build a campaign, to get power through numbers.

The Jewish presence in higher education has been overshadowed by philanthropists. The influential Jews on campus built buildings, not encampments. Jews raised endowments, not flags.

Centers of Jewish studies and Israel studies, partnerships with Israeli universities, and campus Hillels are all signs of Jews thriving in higher education. For a minority that was systematically excluded at so many sites of higher education, this has been a historic achievement. Because of this success, the Jewish community is more likely to show up to an event with the university president and trustees than in the street with the activists. When the struggle turns into one of protest, of mobilizing bodies, we are caught flat-footed. We have no street team.

To be sure, there are a number of smaller, scrappier Jewish organizing efforts such as Bend the Arc, Jews for Racial and Economic Justice and individual congregations. These groups have not yet made serious inroads on campus, however, where Hillel and Chabad are still the dominant players.

The semester is coming to an end, but the protests are not. Liberal Zionists must, as a Jewish community, learn to organize again as a community. Jewish life will need grassroots support, not buildings, in the years ahead.

What does that mean? First, it means adjusting our expectations, because changing hearts and minds takes years, not weeks. We liberal Zionists who believe in a just, democratic Jewish state of Israel must begin to think in 5- and 10-year increments to build collective power again. The next few years will be very hard, and we should prepare ourselves for the long haul.

Second, it means training students and Jewish professionals in effective organizing methods, like those of Jane Mackalevy or Marshall Ganz, who have each developed successful models of organizing beyond the traditional methods of trade unionism. This is not about learning hasbara (roughly translated as “explaining”) or how to sell a talking point in the mold of Israel’s public diplomacy efforts to influence people’s perceptions of the Jewish state. Rather, it is learning a set of skills to listen, build relationships and ultimately recruit others through mutual understanding of our shared values.

Recently, the pro-life movement did this very effectively, maintaining long, ongoing conversations with women without judgment or rhetoric, in the hope of changing minds. The result of this effort is a new generation of young women, both Christian conservatives and progressive humanists, who support abortion bans.

There also needs to be a significant financial investment in building a culture of grassroots organizing. It may be unsexy to Jewish funders, but it will, ultimately, get the best long-term return for our philanthropy. Zionism and Israel are currently radioactive terms on college campuses. To change that, we need to begin a long series of conversations about how these ideas are currently understood, and what they should mean instead.

This involves endless hours of listening, of building relationships, and of understanding before trying to be understood. Once others believe we are interested in a sincere dialogue because we are humble enough to know we have much to learn, we will have space to persuade people. Talking points from the larger world of Israel advocacy, while important at times, only play into a hostile confrontational culture. We need to bring the temperature way down and get back to trusting conversations.

The foundation of what I am calling good organizing is that principled, civil conversation over time, conducted with passion, listening and generosity of spirit, can change people’s minds. This long, slow task is what makes human beings see each other and feel most seen. It is the very substance of democracy, and the very heart of Judaism. It’s time to get organizing.