Threatening Jews is now acceptable — so long as you call them Zionists

This past week saw a new escalation of violent threats against Jews in New York City, in the name of anti-Zionism

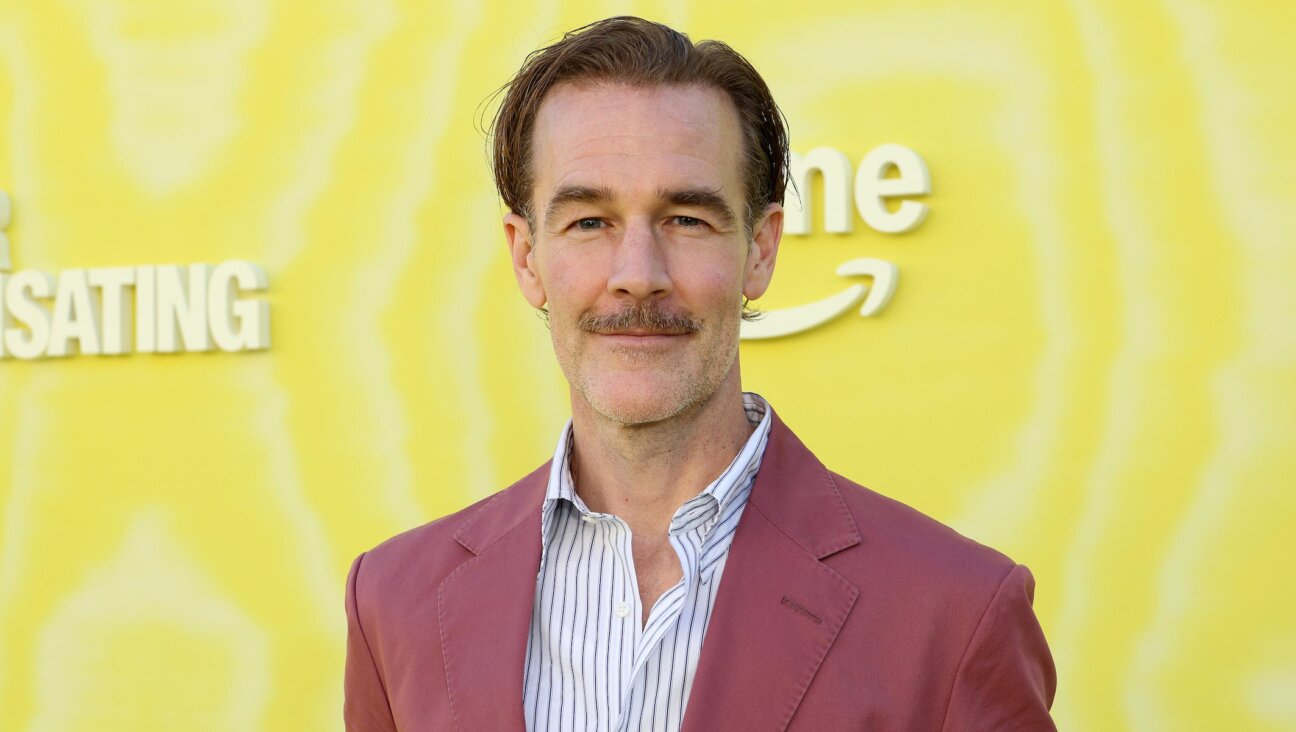

The home of the Jewish director of the Brooklyn Museum, Anne Pasternak, was vandalized early in the morning of June 12, 2024. Graphic by Nora Berman/Screenshot/X

It is now clear all manner of antisemitic sins can be indulged under the guise of opposing Zionism.

On Monday, Within Our Lifetime, a militant pro-Palestinian group that refuses to condemn Hamas’ Oct. 7 terror attack, led protests outside a Lower Manhattan exhibition about the massacre at the Nova Music Festival. They set off smoke bombs; a few carried Hamas and Hezbollah flags; others held signs saying “Long live Oct. 7th.”

On the subway that same night, in a filmed interaction that went viral, protesters leaving that demonstration asked any Zionists to identify themselves and leave the subway car, saying, “This is your chance to get out.” One man wearing a T-shirt with the Hezbollah flag on it harassed a passenger who was wearing a kippah, saying, “Yo we got a Zionist here I see your kippah. You’re not really Jewish,” and “We’re gonna find you and you’ll face the consequences.”

Within 24 hours, vandals defaced the home of Anne Pasternak, the Jewish director of the Brooklyn Museum, along with three museum board members. Red paint and upside-down red triangles — a symbol lifted directly from Hamas’ armed Al-Qassam brigade videos, which use the inverted red triangle emoji to mark Israeli targets — were splashed on their homes’ facades and front doors. A sign was hung across Pasternak’s home labeling her a “White-Supremacist Zionist.”

What all these events made clear: Among those protesting the war, a clear subset is using “Zionist” as a catchall for “Jew.”

The speed at which blatant antisemitic bigotry appears to have become wrapped up in the package of opposing Zionism is breathtaking. So is the number of intelligent people, normally highly attuned to injustice, who are ignoring it.

There have always been those who use these terms interchangeably. What’s new is the boldness of those using it, and the distinction between Jews — a marginalized group worthy of respect — and Zionists — worthy targets of violence.

“Zionists are not Jews and not humans,” read a sign from protesters outside the Nova exhibit.

The survivors of the Nova at the exhibition? It’s OK to retraumatize them, because they’re Zionists, not Jews.

It’s fine to threaten subway passengers who are peacefully minding their own business, because if they’re wearing kippahs, they must be Zionists.

A Jewish museum director, whose home was targeted with a symbol used by a terrorist group to mark their victims? It’s fine, we don’t need to worry about her safety, because she’s a Zionist. (Pasternak’s friends say she has a long history of pro-Palestinian advocacy.)

What it boils down to: If we call you a Zionist, you deserve the consequences — whether they’re public threats, an invasion of your private life, or pure harassment. And if that behavior crosses the line from peaceful protest to aggressive antisemitism, well, Zionists deserve that too.

Worse still, these shifts have been broadly accompanied by an utter lack of accountability from anyone who counts themselves as pro-Palestine when it comes to disavowing this vile behavior. That silence tarnishes a very just movement to liberate Palestinians from decades of Israeli occupation.

The events of this week are obvious bigotry. But I’m not seeing my progressive friends post about it online. I’m not seeing the non-Jewish authors, journalists, activists and lawyers that I so deeply admire for their advocacy on trans rights, immigration, racial justice and criminal justice reform speak up and call out this appropriation of anti-Zionism to mask antisemitism.

I’m not seeing my well-meaning friends who rightfully speak up about the racism of Jewish settlers destroying aid convoys for Gaza, and violently expelling Palestinians from their villages in the West Bank, also condemn this festering hatred present in the pro-Palestinian movement.

To be clear, sometimes anti-Zionism is not antisemitic. But sometimes it is.

I recently saw a post on Instagram about the author’s volunteer efforts to get her block in Brooklyn designated as a landmark, in an effort to protect elderly Black homeowners from predatory landlords. In sharing the many obstacles the volunteers had overcome, my eye caught this line: “We have experienced Zionism first hand and it has been terrifying and taxing.”

Umm … what?

I quickly scanned the rest of the post. Zionism popped up again: “To be preserving Black Bedstuy in the face of Zionism. At a time when our world needs to be free of it!!”

There are innumerable definitions of Zionism, but none of them remotely encompass efforts to alter a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Gentrification and displacement are very real phenomena that disproportionately affect Black and brown people, but they have nothing to do with Jewish self-determination.

The most likely scenario: This person interacted with a Jewish landlord or Jewish-owned management company in their conservation battle. And while scummy landlords are the worst — I’ve lived in New York City for 13 years, I know — they come in all ethnicities and religions.

These sentences were straight-up, indisputable antisemitism, but the likes and “Congrats!” and “Good work sis!” cascaded onto the post, including from a journalist who works at The New York Times. The author had also tagged a New York City Council member who had aided their group.

The protests outside the Nova exhibition and the vandalism of Brooklyn Museum executives’ homes were universally decried by politicians across the political spectrum, most notably by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has not always pleased the Jewish community with her advocacy against arming Israel. (Ocasio-Cortez, who encountered severe blowback from progressives and false accusations of being a paid shill for AIPAC after speaking out against antisemitism in a livestream earlier this week, is now seeing the consequences of calling out the moments when anti-Zionism is antisemitism.)

By not uniformly condemning these bad actors within the movement, supporters of Palestinian liberation are tanking their movement’s credibility, and giving ammunition to militant pro-Israel advocates who seek to discredit the entire project by dismissing it as antisemitic. How can anyone take a group like Within Our Lifetime seriously as a liberation movement, when people protesting within it say, “Zionists are not Jews and not human”? When it chooses to protest not outside the Israeli consulate, but at a memorial to victims of terror?

The collapse of Zionist as a useful or effective definition began long ago. In an op-ed for the Forward early this year, Lux Alptraum pointed out how the semantics of how the term is used can obscure shared values. “If two people can agree that they want peace and freedom for both Palestinians and Israelis,” she wrote, “does it matter if one of them identifies as Zionist and the other anti-Zionist?” Tamar Glezerman, the Israeli-American co-founder of Israelis for Peace whose aunt was murdered at Kibbutz Be’eri on Oct. 7, told The Guardian that the term “Zionist,” as it’s currently used, “could mean anything between someone who believes in two states coexisting peacefully to code for Jews who don’t deserve safety or life.”

The slipperiness of who a “Zionist” is has allowed for antisemitic rhetoric and violence to flourish. How far will it have to go until self-proclaimed allies of Jews call it out?