Back to the Middle Ages?

As other explanations for America’s invasion of Iraq have been cast into doubt, a new dawn for human rights has become one of the rationales invoked by the Bush administration to justify the war. So it’s not surprising that the American-led Coalition Provisional Authority would boast of its efforts to improve the lot of Iraqi women. The authority’s Web site states, “The United States is working with women in Iraq on programs that will broaden their political and economic opportunities and increase women’s and girls’ access to education and health care.”

Unfortunately, the outlook for Iraqi women is far from positive. In late December, the Iraqi Governing Council, made up of 22 men and 3 women handpicked by the United States, secretly passed a resolution that would establish religious courts for each of Iraq’s three major religious groups — Sunni, Shiite and Christian — for adjudication of all issues of “personal status,” code for everything having to do with women (marriage, divorce, child custody). This would overturn Article 2 of Iraq’s 1959 Law of Personal Status, which provides that the existing “courts of personal status” apply Shariah, or Islamic law, only in the absence of a specific civil code law dealing with the question at hand.

Religious courts are bad news for women. Progressive Iraqi women, who thought liberation was going to include them, were shaken by the resolution’s passage, fearing, as Zakia Ismael Hakki, a retired female judge, told The Washington Post, that they could be returned to the Middle Ages. Moderate Governing Council members — men as well as two of its three women members — have spoken out against the decision and say only one-third of the council backed it. Council members who attended the World Economic Forum at Davos last month privately insisted that the resolution was rushed through at a time when a majority of the council’s members were not even present. Thousands of women have turned out to demonstrate against — and, alas, some for — the resolution.

The resolution cannot take effect without the approval of Iraq’s American administrator L. Paul Bremer, who is unlikely to grant it. Indeed, Bremer has hinted that he would veto any Iraqi constitution that has as its basis Islamic law. The Americans, however, will turn over power in June, and the controversy over the Governing Council resolution underscores the precarious situation in which Iraqi women find themselves in the wake of the invasion.

The irony is that Iraqi women could wind up, in many important respects, worse off than they were before. Iraq was not paradise for women — or anyone else — under Saddam Hussein. However, until the 1991 Gulf war, the status of women in Iraq was high compared to that of women in other Middle Eastern countries. The Ba’athist regime understood that women’s participation was necessary to the rapid economic growth it sought. Its aggressive drive to eradicate illiteracy included women; tribal and religious leaders who stood in the way were threatened with prosecution. Women’s literacy and employment shot up: 75% of women were literate, and in teaching-related fields, for instance, nearly 40% of positions were occupied by women.

That relatively high status began to unravel following the 1991 Gulf war, when Saddam Hussein decided to embrace tribal and religious traditions as a tool to consolidate his power. This, and the economic hardships that resulted from U.N. sanctions, set women back. Due to the scarcity of jobs, women were driven out of the labor force. Labor law, criminal law and family law were amended by legislation and governmental decree to the disadvantage of women. The numbers of so-called “honor crimes” — in which men kill their female relatives for supposedly besmirching their family’s honor — skyrocketed; according to the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Violence Against Women, 4,000 women and girls were murdered in presumed honor crimes between 1991 and 2001, with virtual impunity for the killers.

The situation for women was worsened by the political vacuum created by the American invasion. Religious institutions have rushed to fill the void, particularly in the cities and towns south of Baghdad. Instead of liberation, for women employment opportunities are shrinking, they are increasingly being pressured to don the veil and ad hoc Shariah courts are adjudicating their most basic interests.

Activist Iraqi women fear the undoing of decades of secular progress. They anticipate that religious fundamentalists will use their new political muscle to push for changes in civil law such as unilateral divorce (“repudiation,” which was banned in Iraq in 1959), abolition of the right to alimony in favor of Shariah-approved temporary support, an easing of the way to polygamy (now extremely difficult), a lowering of the current minimum age of marriage (now 16 years old) and restrictions on the right of female children to inheritance. They fear that women who held professional jobs, who traveled alone, who were accustomed to chatting in public with men to whom they are not related, will suddenly be unable to do so — at least not without risking censure, divorce or even death.

The decline in the status of Iraqi women, of course, cannot entirely be blamed on the United States. But neither can the United States claim it has rescued Iraqi women, any more than it rescued Afghan women, who have been returned to Taliban-style repression in most of the country outside of Kabul. And the unintended consequences of the misguided adventure in Iraq may continue unfolding for many years to come.

Kathleen Peratis is counsel to Outten & Golden LLP and a member of the board of Human Rights Watch.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

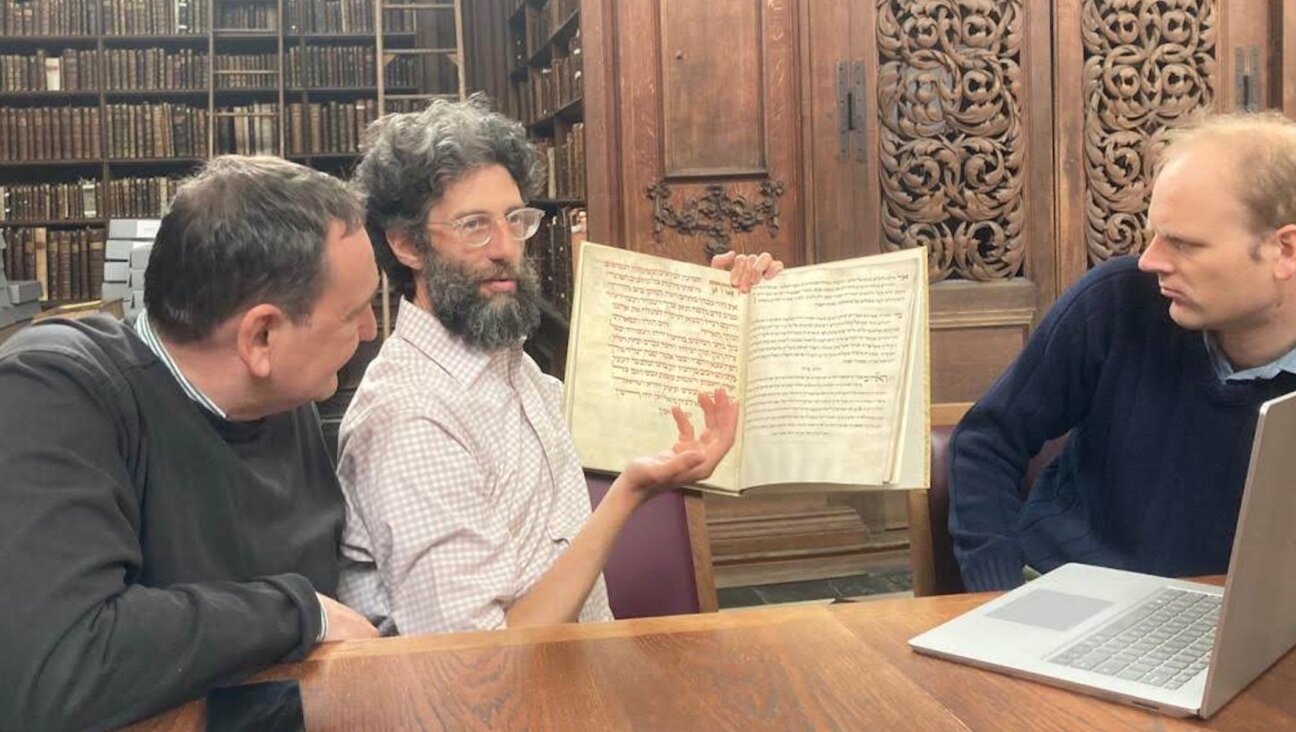

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

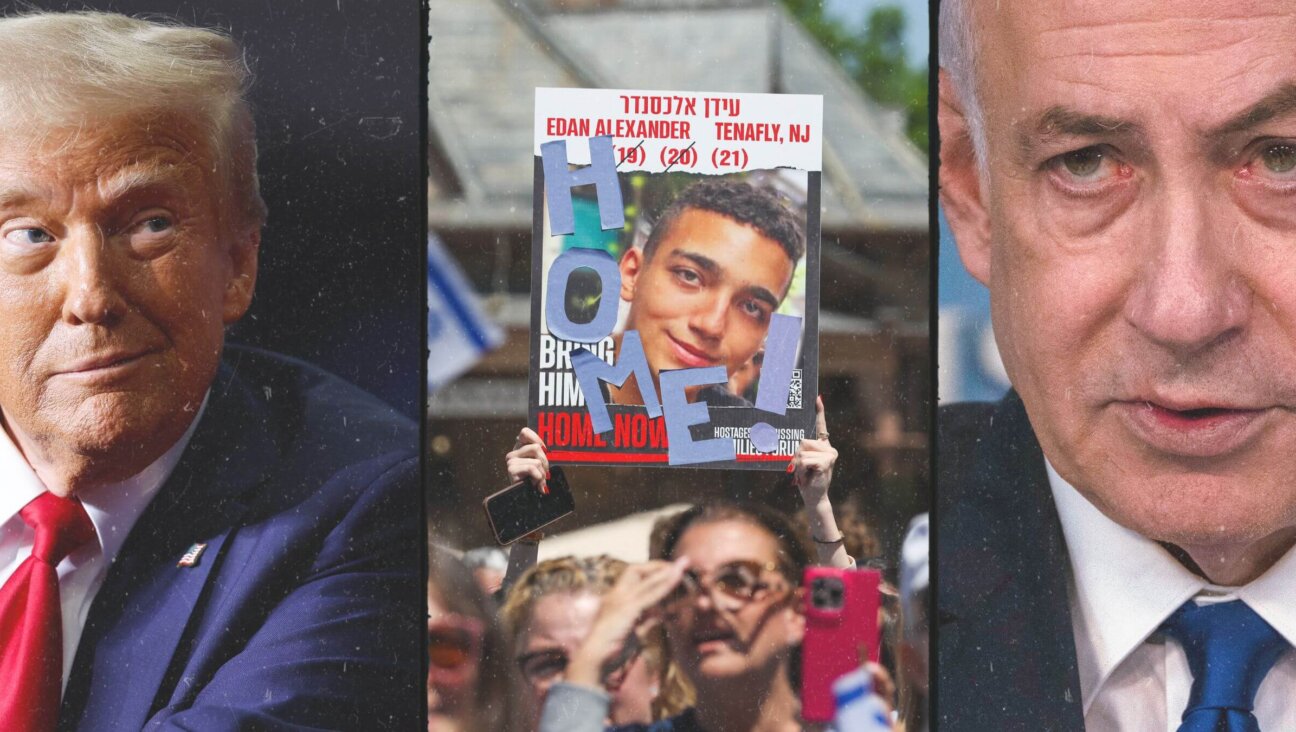

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.