My mother survived the Holocaust — only to have antisemitism land on her doorstep here.

In Somerville, Massachusetts, our “Stand With Israel” sign was attacked from the right and left

Brian Sokol’s mother, Helene Hirschberg Sokol, pictured as a young girl in Antwerp, Belgium (left) and later in Somerville, Massachussetts (right.) Helene passed away in January this year. Courtesy of Brian Sokol

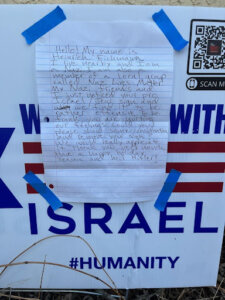

SOMERVILLE, Mass. — I never showed my mother, a Holocaust survivor, the letter a self-proclaimed member of “Nazi Lives Matter” taped to the “We Stand With Israel” sign on our front lawn in December. Nor the note that followed a few days later reading “Fight Colonialism, Imperialism, and All Domination. Free Palestine.”

She was 81 and ill with kidney disease and diabetes, though since the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attack had been refusing my help in getting her something to eat by saying, “I have to be strong for Israel.” How could I tell her that the hatred she barely escaped as a baby in Nazi-occupied France had now literally arrived at her doorstep in Somerville, Massachusetts?

Mom died on Jan. 26, the morning after our City Council passed a resolution calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. Nine months later, as Jews around the world prepare to mark the Hebrew anniversary of the attack on Simchat Torah Thursday evening, local and national Jewish groups have been fighting off a new effort to get the council to join the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel at its meeting that night.

So my grief over the loss of my mother remains intertwined in Israel’s ongoing wars with its enemies and the arguments about it flaring up in my own neighborhood. The singling out of Israel as the sole bad actor on the world stage and the questioning of the Jewish state’s right to exist smack of the same old antisemitism my mother, Helene Hirschberg Sokol, thought she’d escaped decades ago.

Born in a convent

Helene’s grandparents owned a hotel in Antwerp, Belgium, where her father was in the diamond trade. As the Nazis rounded up Antwerp’s Jews for transport to death camps in summer 1942, her parents — my grandparents — and aunt stepped out of line and escaped. They made it to Lyons, France, which was under the control of the Vichy government, before my grandmother, who was nine months pregnant, had to stop.

They hid in a convent. My mother was born in that convent on Sept. 2, 1942. A few weeks later, they bribed an ambulance driver to take them close to the border with Switzerland, then crossed it by foot at night.

The grown-ups took turns carrying the tiny baby through the mountainous terrain. At one point, my grandfather fell into a dark ditch; had he not passed my mother off to my grandma a few minutes before, she likely would have died.

Instead, she became the youngest occupant of the Swiss refugee camps. Until the time of her death, my mother regularly had to explain to government officials why she did not have a birth certificate — and why there was no hospital or municipality to call to get one. These dumbfounded bureaucrats included, rather ironically, the Germans in charge of dispensing Holocaust reparation funds.

Over the next few years, my grandfather helped others cross the Swiss border. My great aunt married an emissary from Palestine, and they helped European Jews migrate there. Had a Jewish state already existed, perhaps the Nazis would not have been able to kill 6 million of our ancestors.

Trauma in the background

Zionism emerged in the late 1800s as a reaction to thousands of years of exile from the Jewish homeland, defenselessness, and the hatred and oppression that entailed. The Holocaust was the ultimate expression of this oppression, and the final rationale for the Jewish state, which we now call Israel.

But Zionism was not just a reaction to antisemitism; it also embodied a rebirth of the Jewish nation and recognition of Jewish solidarity and peoplehood. Zionism emphasized a common Jewish history and future; a common language, culture, religion and connection to a sacred land.

Echoes of the Holocaust, antisemitism and Zionism did not consume Helene’s life, but remained present. After her family moved to the United States in 1951, she joined Young Judaea, a Zionist youth movement, went to Jewish summer camps and spent 1960-61 — considered Israel’s bar mitzvah year — studying and touring in Israel. It was the year of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the primary architects of the Final Solution.

Later, she named me Brian rather than something that sounded Jewish. But she sent my sister and I to the same Young Judaea camps and Israel program she attended. And in 1985, when President Ronald Reagan laid a wreath at the grave of German WWII soldiers in Bitburg, my mother flew there to protest.

The trauma was never too far in the background. On Sept. 11, 2001, my mother was flying home from Israel, where she’d attended the unveiling for the aunt who’d escaped to Switzerland by her side. The plane was forced to land in Wichita, Kansas, whose local Jews had decided to house passengers at a local summer camp. Mom confronted the administrator: “Are you telling a bunch of Jews at the outbreak of a war to get on a bus and go to a camp?”

Solidarity and hatred

But nothing compared to her reaction to Oct. 7. She watched the news with horror as she thought about family and friends once again exposed to a coordinated, murderous pogrom in the very country meant to keep them safe.

Among the nearly 1,200 people Hamas slaughtered that day was at least one baby younger than Helene was on that trek to Switzerland — and senior citizens older than she had become.We put up the “Stand With Israel” sign to express solidarity with the Jewish people in this time of need. But many of our Somerville neighbors reacted with hatred.

The sign was stolen twice. We replaced it both times. Then came the notes.

“Hello! My name is Heinrich Eichmann,” said the first one, written on loose leaf paper. “I live nearby and I am a Nazi. I am also a member of a local group called Nazi Lives Matter. My Nazi friends and I just noticed your pro-Israel/Jew sign, and we find it rather offensive. To be frank, you are hurting our feelings.”

It was impossible to know if this was serious or an attempt at satire. The note ended, strangely, by wishing us a happy holiday season and then, “Heil Hitler.”

My 10-year-old was afraid to leave the house. So, we removed the sign.

The end of my mother’s journey

Four weeks later, an ambulance took my mother to the hospital for what would be her final journey. As I sat by her deathbed, my phone was blowing up with texts about the Somerville City Council ceasefire resolution. While I understood the impulse to want to end the violence in Gaza, the resolution felt like a denial — once again — of the Jewish people’s right to defend ourselves.

My mother and her family knew the consequences of that. I was grateful that the resolution was amended to include a recognition of Israel’s self-defense needs and to condemn the Oct. 7 attacks. Additions were made to criticize anti-Israeli rhetoric as well as anti-Palestinian, and to remove language equating Palestinian political prisoners with hostages abducted by Hamas.

The measure passed 9 to 2 after three hours of deliberation. Three days later, we buried my mother.

The first High Holidays without her would have been difficult enough, but it was made harder by the fact that Somerville for Palestine has been circulating BDS petitions for weeks. It was hard not to be suspicious that they targeted Thursday’s City Council meeting, when observant Jews would be in synagogue for Simchat Torah, in hopes that few would show up.

The Anti-Defamation League and local pro-Israel groups pushed back hard, and when the council meeting agenda was posted on Tuesday, the BDS resolution was not on it. But it could still be added last-minute — or taken up at the next meeting.

On this holiday, we complete the reading of the Torah scroll, and immediately start again from the beginning. As my mother’s birth and death remind us, antisemitism also has its own endless cycle.

Zionism was supposed to be the answer, but hatred still exists in the Middle East — and in Somerville — as it did in 1942 Europe. We must stay vigilant to the warning signs and, as my mother said while slowly pushing herself out of her chair in her last weeks, “Be strong.”