How a Holocaust philosopher can help us make sense of Trump’s disgraceful Jan. 6 pardons

For Vladimir Jankélévitch, some acts were beyond the realm of forgiveness

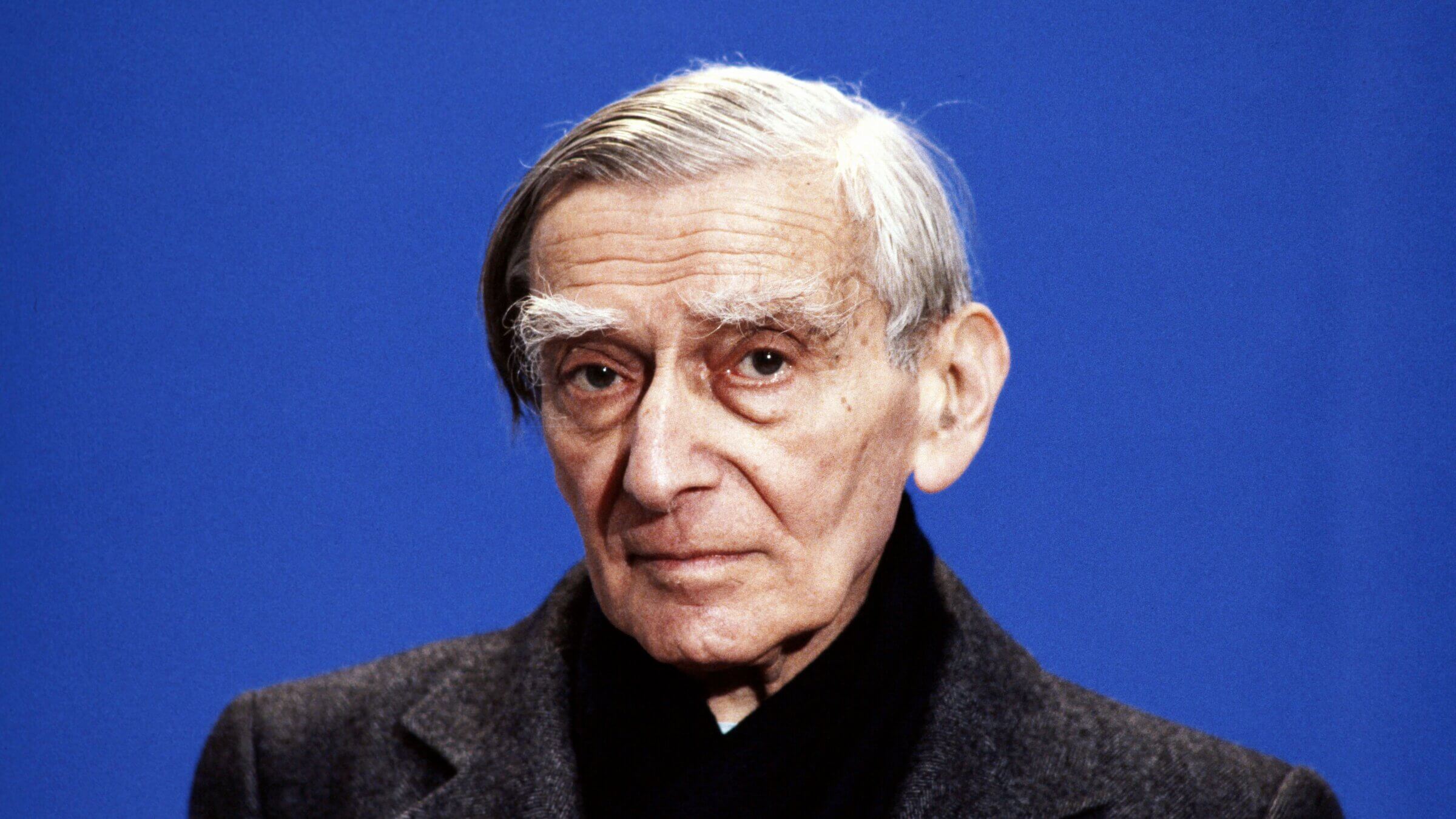

Vladimir Jankélévitch, circa 1981. Photo by Getty Images

“To err is human, to forgive is divine.” As an instance of poetic meter (iambic pentameter, to be precise), Alexander Pope’s famous line works superbly. As a matter of ethics, though, it works less well. Take the case of President Donald Trump’s pardon of the Jan. 6 insurrectionists, which makes the counter-case in the same meter: To err is human, to forgive is a disgrace.

Were he alive today, Vladimir Jankélévitch might well be making this very case. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the death of Jankélévitch, one of France’s most important yet least recognized moral philosophers. This lack of recognition is not surprising, in part because his books often suffer from a lack of clarity. Long sentences and even longer paragraphs spill across several pages, peppered with strange words that Jankélévitch loved to string together, as well as exclamation marks. Lots of exclamation marks!

As his friend Emmanuel Lévinas suggested, Jankélévitch “mistrusted the facile habits of language, its verbal habits and its rhetoric.” The frequent knottiness of his language, though frustrating, can also be clarifying; there are ethical issues that demand that we stop and look, pause and reflect.

Jankélévitch’s approach to ethics was shaped by personal experience. The child of Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants, he graduated in 1926 from the École normale supérieure, the university that also produced Émile Durkheim and Henri Bergson, Raymond Aron and Simone Weil, Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault. World War II left as lasting an impression, however, as his classes at E.N.S. Serving as an army officer, Jankélévitch was wounded during the battle for France. That wound, however, was not as great as the one made by the antisemitism of the Vichy regime, which forced him from his post as a professor of philosophy in Toulouse.

Curiously, Jankélévitch was equally wounded by the exterminationist ideology of Nazi Germany. According to his friend Jacques Madaule, Jankélévitch, who was a gifted pianist and thought and wrote deeply about music, was stunned that the country which produced a Schubert also produced the Shoah. His friend’s wound never healed, Madaule remarked, “not just because he was a Jew, but because he was a human being.”

It was also as a human being that Jankélévitch joined the Resistance. His underground activities ranged from teaching clandestine courses on philosophy to the writing and distributing of Resistance tracts and journals. Though he rejoiced at the liberation of France in 1944, Jankélévitch could never free himself from the significance of what occurred during the war. He felt “the necessity to prolong in myself the sufferings from which I had been saved.” He felt blessed, but also burdened that he and his parents had not been captured and deported to Auschwitz — a stroke of fortune that “imposed upon me a sacred duty of witnessing.”

Much of his work bears the imprint of his wartime experience. For example, Le Mensonge, or The Lie, explored the ethical consequences of life under a regime marinated in mendacity. This has a certain relevance for Americans today, of course, but more relevant are perhaps his most controversial books, L’Imprescriptible, or The Imprescriptible, and Le Pardon, or Forgiveness.

The former book initially appeared in the newspaper Le Monde in 1965 as a letter, albeit one which ran several pages. Jankélévitch sent the letter in response to the debate in West Germany over whether to apply the 20-year statute of limitations to all war crimes, including crimes against humanity. Such a gesture horrified Jankévélitch, who claimed no future was feasible if this past — one that witnessed the systematic extermination of an entire people — were forgotten or forgiven. “It is incomprehensible,” he wrote, “that time, a natural process without normative value, could have a diminishing effect on the unbearable horror of Auschwitz.” What took place at the death camps was “an assault against the human being as a human being, not against such and such a person, inasmuch as they are this or that.”

We can no more forgive this event, he continued, than we can “give life back to that immense mountain of miserable ashes. One cannot punish the criminal with a punishment proportional to the crime. Strictly speaking, what happened is inexpiable.” While we can do nothing to change this fact, only the victims can do something — namely, forgive. But, of course, they cannot because they are dead. Ultimately, we can do nothing, including pardon those guilty of this crime, because “pardoning died in the death camps.” We cannot, he insisted, move on from what Auschwitz bequeathed to the world.

Jankélévitch argues that when we talk about forgiveness, we are talking about many things, none of which is true forgiveness. It is often reflexive, “flowing from intellection in the same way that the secretion of gastric juices flows from the ingestion of food,” or practical, expressing the desire to move on: “How to be rid of something is not a moral problem. The philosophy of good riddance is a caricature of forgiveness.” Nor is it found in the goal of reconciliation or the hope of redemption. The reasons for these gestures are mostly transactional, given in order to get on with life.

Real forgiveness is of a different magnitude, Jankélévitch affirms in his book Le Pardon. “In a single, radical, and incomprehensible movement, forgiveness effaces all, sweeps all away, and forgets all.” It is beyond ethics, beyond justice, but perhaps not beyond our understanding. Were it not for the possibility of true forgiveness, there would be no possibility to truly reimagine our world and ourselves. The supernaturality of forgiveness, Jankélévitch concludes, does not mean my opinion of the guilty person has changed. But “against this immutable background it is the whole lighting of my relations with the guilty person that is modified, it is the whole orientation of our relations that finds itself inverted, overturned, and overwhelmed!”

Jankélévitch’s examination of pardoning helps us measure the enormity of Trump’s pardon of the insurrectionists. Obviously, there is no world in which the actions of the worst offenders — including the men and women who assaulted police officers, hunted down members of Congress, and demanded the hanging of then-Vice President Mike Pence — could be compared to the actions of the architects and enablers of the Shoah. To claim otherwise would be literally nonsensical.

At the same time, Jankélévitch’s reflections remind us that, though these men and women have been forgiven by the president, we cannot move on from what both this event, and Trump’s presidential act, have bequeathed to this nation. We will live with the many dire consequences for many years to come, consequences that may well spell the end of our imperfectly realized yet impossibly inspiring democracy. For this reason, while the president forgave the insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol, one cannot help but believe that those who have given their lives for the ideals of our country would never do the same.