Mike Huckabee’s stunning, terrifying new gift to the Israeli right

If the US abandons a two-state solution, Israel will be forced to face existential questions with no good answers

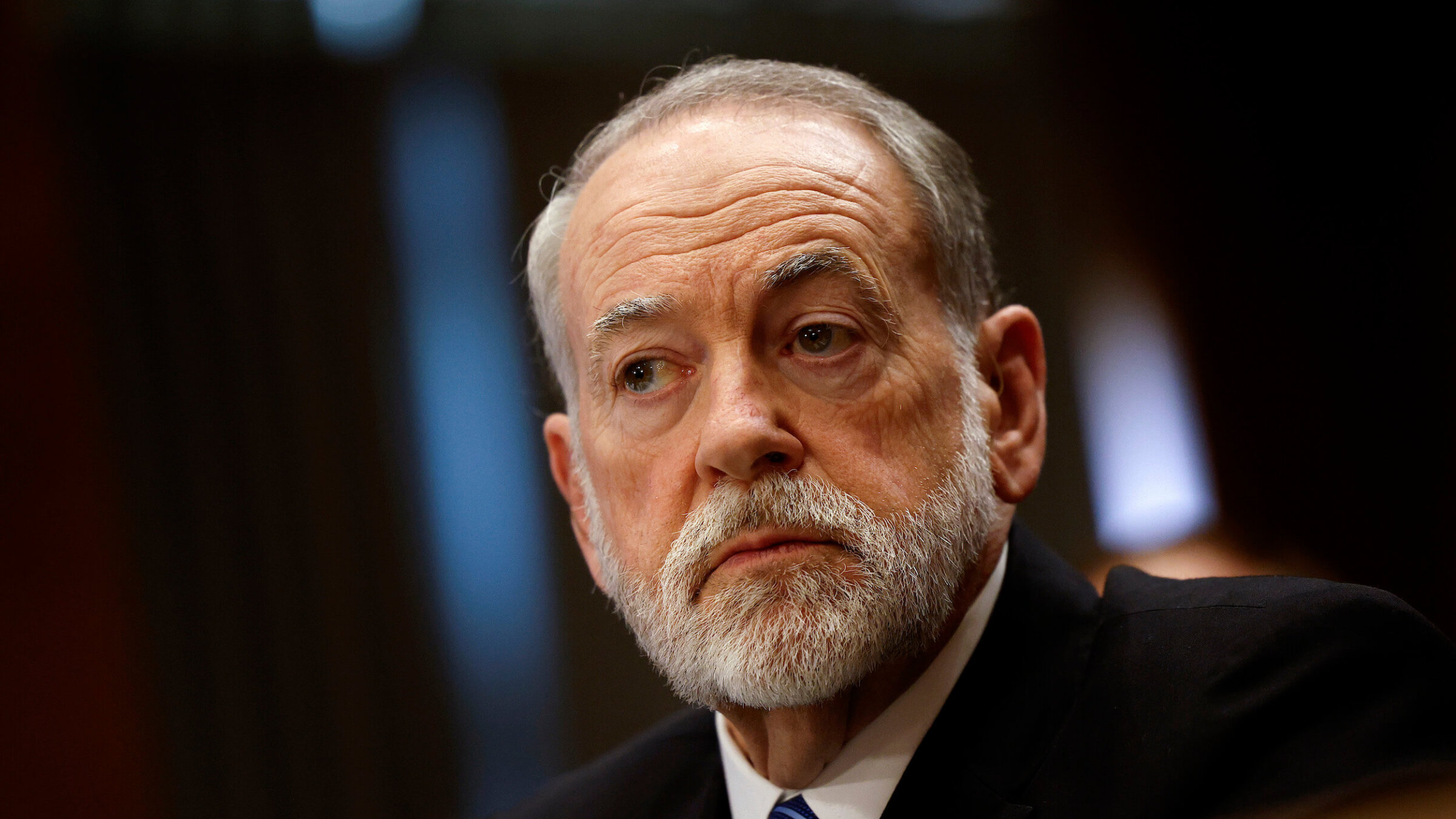

Mike Huckabee, U.S. ambassador to Israel, testifies during his Senate Foreign Relations Committee confirmation hearing on March 25. Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Would the creation of a Palestinian state be a favor to the Palestinians — or a lifeline for Israel?

That’s the deeper question raised by recent comments from Mike Huckabee, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, who said in a Tuesday interview with Bloomberg News that the United States is no longer pursuing the goal of an independent Palestinian state — and that, if one were created, it should be carved out of “a Muslim country,” rather than any current Palestinian territories. “Does it have to be in Judea and Samaria?” he asked, using the Israeli right’s biblical term for the West Bank.

Huckabee has long aligned himself with Israel’s religious-nationalist right: He has claimed that “there is no such thing as a Palestinian”; rejected the term “occupation” to refer to Israel’s presence in the West Bank; and referred to West Bank settlements as “neighborhoods” and “cities.” During a 2017 visit to the West Bank, he declared that “Israel has title deed to Judea and Samaria.”

His new statement may or may not reflect a fully formed policy; President Donald Trump’s administration has proved, even in a few short months, to be seriously changeable in its approach to the Middle East. But in an era where trial balloons can become doctrine, it represents a major departure from decades of U.S. diplomacy — and while the Israeli right might celebrate it, the implications for Israel’s future are actually dire.

Israel’s fundamental contradiction

Approximately 15 million people live in the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea — roughly half of them Jewish, and half Arab. If Israel comes to control all of that territory while denying voting rights to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, it will no longer be able to credibly claim to be a democracy. There would be serious implications to the end of that claim: Israel’s own population mostly wants the country to be a democracy, and its position as an ally of Europe and the United States largely depends on that status as well. (It’s arguable that, after 58 years of partial Israeli control of both territories, the situation is already beyond indefensible.)

But if Israel grants equal rights to all, it will instantly cease to be a Jewish-majority state. In that case, the Zionist dream would dissolve. Many Israeli Jews would, in response, likely leave. The demographic balance would tilt, and, I have little doubt, the state would eventually be renamed “Palestine.”

It’s basic math. Unless Israel is prepared to expel millions of Palestinians — which its ultranationalists actually are, but they are the minority — the only way to preserve Israel as both a Jewish and democratic state is through the creation of a Palestinian state.

The counterargument: No state needed

Yes, there is a counterargument — one that Huckabee and his ilk know well.

It begins by denying the very premise. The Palestinians, critics say, are not a distinct people with compelling ancient claims to modern statehood. They are Arabs of the Levant, ethnically and culturally indistinguishable from Syrians, Jordanians and the Lebanese. Before the creation of Israel in 1948, there was no talk whatsoever of a separate “Palestinian nation.”

Why, then, is it so critical that they receive a 23rd Arab country — especially when none of the existing ones is a functioning democracy?

Nation-states are a creation of recent centuries, and ethnic groups — yes, including Jews — do not have an automatic right to one. The Kurds — an ancient and stateless people numbering over 30 million — have no state. Neither do the Catalans, Berbers, Druze or Tibetans.

As for the Palestinians, the Arab countries have never done much to further their statehood. Egypt controlled Gaza and Jordan controlled the West Bank between 1948 and 1967. In those two decades, they made no moves toward Palestinian statehood. And Israel and the Palestinians could never come to terms on an agreement, beyond the autonomy zones set up in the 1990s.

But beyond that, naysayers argue, why should Israel accept the risks that would accompany the creation of a Palestinian state? Gaza was already an experiment in Palestinian autonomy — a disastrous one. In 2005, Israel pulled out every soldier and settler. The Palestinian Authority, led by the relatively moderate Fatah party, was in charge. But within two years, Hamas seized control, turned Gaza into a heavily militarized fortress, and launched years of rocket fire into Israeli cities — culminating in the horror of Oct. 7, 2023, when about 1,200 people in Israel were slaughtered in a barbaric cross-border attack, sparking the present devastating war.

Even many liberal and moderate Israelis, who care about the Palestinians, are wary of repeating the same experiment with the West Bank. The territory overlooks Israel’s main population centers and surrounds Jerusalem on three sides. At its narrowest point, Israel would be just 12 miles wide. A hostile or unstable Palestinian state there could be strategically catastrophic — a recipe for a disaster that could dwarf Oct. 7.

So what’s the alternative?

If an independent Palestinian state is too dangerous and eternal occupation is unsustainable, what options remain?

Several imperfect scenarios are worth considering. One is a partial Israeli pullback from some West Bank territory — not going so far as to reestablish the pre-1967 lines, and not including the half of Jerusalem that the Palestinians demand, but enough to reduce friction, create a contiguous Palestinian territory, and maintain Israel’s demographic integrity.

This move would have to be heavily conditioned. The resulting territory should be totally demilitarized, with its airspace, borders, and security infrastructure controlled or monitored by a regional or international force.

A third option — which sounds radical, but is far from new — would be for Gaza to return to Egyptian control, while part of the West Bank would be absorbed again by Jordan.

This would acknowledge that the modern concept of “Palestine” as a sovereign project is a relatively recent invention, and fix the issue of Palestinian statelessness. Yet both Egypt and Jordan have long rejected such proposals, wary of internal destabilization and the burden of absorbing a volatile population.

But again, in the absence of better ideas, it may resurface in future negotiations. Big enough incentives can change minds.

A vacuum in Washington, noise on the world stage

None of these plans are perfect. But the U.S. should be actively pressing forward with grand plans for spreading peace in the region, exploiting the current weakness of Iran.

Instead, the White House appears to have chosen passivity. What Huckabee’s comments signal most powerfully is that the only international actor with massive leverage over Israel may be vacating the stage.

This comes as the United Nations prepares to host a conference on the two-state solution, and several European states, led by France, are considering symbolic recognition of a Palestinian state, albeit with conditions. The global conversation is inching forward, however awkwardly, as the U.S. backs away.

Then again, we cannot rule out another case of crazy Trumpian chess. Trump’s February suggestion that the U.S. might “buy” and “own” Gaza and remove its population was rightly dismissed as absurd — but it spooked Arab states into proposing actual helpful plans for a postwar arrangement. Those plans, which involve a locally governed Gaza with Arab backing, may still form the basis of a future roadmap.

So it’s possible Huckabee’s latest statement is another tactical provocation meant to jolt Israeli leaders into serious thinking. Trump is often impulsive, but he has a certain schoolyard cunning. Even as absurdist theater, his provocations can reshape the playing field.

A key playing field is Israel’s electorate. Elections must be held by next year. Perhaps the understanding that America will not save them will get Israelis to elect a leadership that is rational — one that understands the Palestinian problem is existential.