Should we fear that Trump is this generation’s Neville Chamberlain? In a word, yes.

Trump’s summit with Putin mirrors Chamberlain’s meeting with Hitler in stunning and sobering ways

Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, Aug. 15, 2025 in Anchorage, Alaska. Photo by Getty Images

Prior to last week’s summit meeting between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, many political leaders and commentators, not to mention tens of millions of Ukrainians, had feared it would be a second Munich. This phrase of course refers to the 1938 agreement in which British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain gifted Adolf Hitler with a vast chunk of Czechoslovakia without first checking with the Czechs. In return, Chamberlain proclaimed that he had won “honor and peace for our time,” only to grasp a year later that he had instead won dishonor and war for his time.

As it turns out, the fears over Alaska 2025, the event where a few days ago a convicted felon rolled out a red carpet for a war criminal, were justified. If not quite a repeat of the Munich Agreement of 1938, it resembled this earlier diplomatic disaster in ways that were both expected and unexpected.

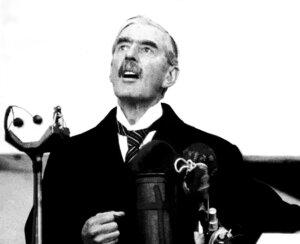

Chamberlain would, I think, agree. In fact, he was responsible for the invention of the modern summit. The offspring of a Conservative political dynasty, Chamberlain started out as a successful businessman from Birmingham and, upon entering politics as the city’s mayor, went on to serve with éclat in various conservative governments. Thanks to his well-earned reputation for good character and great competency, he became prime minister in 1937.

As the historian Tim Bouverie argues, however, Chamberlain never shed his conviction that international conflicts, like municipal problems, could be resolved in a “practical and businesslike” manner. Even when those conflicts were the work of psychopaths. The British leader, whose trademark was a rolled-up umbrella, maintained this attitude when the man whose trademark was raging diatribes threatened to invade Czechoslovakia in 1938.

Hitler’s ostensible reason was to guarantee the safety of German speakers living in the Sudetenland, a resource-rich region that was also home to the country’s famed metal and chemical industries, as well as strategically vital fortifications. Clear-sighted contemporaries like Winston Churchill, and not just hind-sighted historians, saw that Hitler’s goal was not to defend fellow German speakers in another country, but instead to destroy the last remaining democracy in Eastern Europe.

Chamberlain was hardly blind to the danger Nazi Germany posed not just to Czechoslovakia, but to Europe. Due to the Rube Goldbergian structuring of treaty commitments, a German attack on Czechoslovakia would oblige France to declare war on Germany, which in turn would drag Great Britain into the conflict. No less important, there was a widespread and well-founded fear that Hitler might not be amenable to reason. The minutes of the cabinet meetings, as well as Chamberlain’s private correspondence, abound in references to Hitler as a madman and lunatic.

Yet Chamberlain also abounded in self-confidence. As the unrest of Sudeten Germans, incited by Hitler, grew increasingly violent over the summer, Hitler’s speeches grew increasingly bellicose. By early fall, when war threatened to engulf the entire continent, Chamberlain hit upon a novel idea. He would fly to Germany and meet with Hitler one-on-one to persuade him against invading Czechoslovakia. This approach appealed not only to Chamberlain’s sense of practicality — “One could say more to a man face-to-face than you could in a letter” — but felt that it would also appeal to Hitler’s ego. “It might be agreeable to Hitler’s vanity,” he told his stunned cabinet, that “a British prime minister would take this unprecedented event.”

Unprecedented was an understatement. Describing Chamberlain’s decision as “breathtaking,” The New York Times declared that “no prime minister has ever made a gesture so unconventional, so bold and in a way so humble.” European leaders, including Édouard Daladier, the French prime minister, were also caught on the backstep. Though Hitler was no less surprised, he accepted Chamberlain’s offer, agreeing to welcome him at his retreat, the Berghof in Berchtesgaden, nestled in the Bavarian Alps.

And so, on Sept. 15, Chamberlain, who had never flown before, climbed into a Lockheed Electra — the same model airplane in which, one year earlier, Amelia Earhart disappeared over the Pacific — and took off for his meeting in Germany. Safely landing in Munich, Chamberlain and his small group were taken by train to Berchtesgaden where, a short while later, he and Hitler, accompanied only by a translator, met in private for more than two hours. Chamberlain and his aides left the following morning, surprising not just the press but his own government, which had expected a stay of three, perhaps four days.

The rest is history. At the end of the meeting, Chamberlain had agreed not just to the autonomy of the Sudetenland, which was Hitler’s initial demand, but also to the region’s de facto secession. He did so having consulted with neither his cabinet, the French, nor the Czechs. Over the course of the next two weeks, as Chamberlain tried to win over his ministers and Daladier, Hitler delivered ever-more-threatening speeches. After a second meeting between the two leaders at the spa town of Bad Godesberg, Chamberlain left convinced that, after gobbling up the Sudetenland, Hitler’s appetite for yet more territory would be satiated.

We know how that history ended; so, too, did Chamberlain. Years later, long after the death of Chamberlain in 1940, his parliamentary private secretary Alec Douglas-Home remarked that as soon as his boss, standing at the door of 10 Downing Street, announced that he had won peace for our time, he knew that he was telling a lie. “He knew at once that it was a mistake, and that he could not justify the claim. It haunted him for the rest of his life.”

This history, which unfolded less than a century ago, parallels in stunning and sobering ways the Alaska summit between Trump and Putin. The blinding self-confidence of one of the leaders that he could cut a deal and the uncanny ability of the other to play his opposite. The belief of one leader that events in a faraway land with people we know little about was not worth going to war for, and the conviction of the other that war was the answer to all his problems. The faith of one leader in his ability to forge a relationship with the other, and the cunning of the other to flatter this faith.

The list goes on, and this particular history is still unfolding. Yet no matter how it does end, here are two things we do know. First, as Churchill declared in his funeral oration for Chamberlain in 1940, his predecessor was a man of conscience and decency. Second, that our president has neither of these virtues and will not be haunted by the outcome of the unconscionable role he has played in what promises to be a disaster for Ukraine, Europe, and us.