‘A long record of failure’: Is it time to put the two-state solution to rest?

Two Oslo negotiators argue in their new book that it’s time to reckon with narratives, not logic

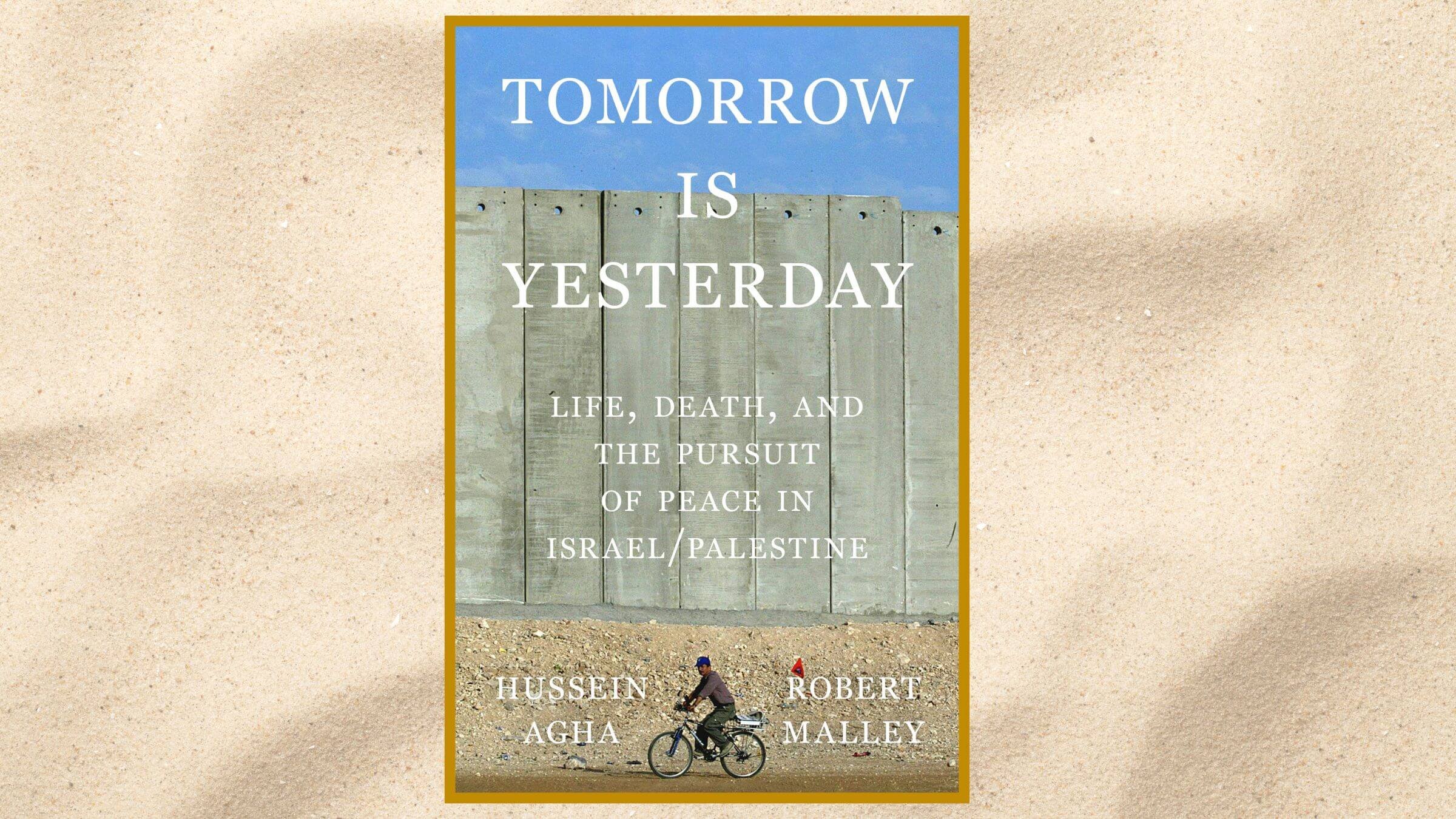

Hussein Agha and Robert Malley, two insiders to the negotiations between the Israelis and Palestinians, have co-written a book that excoriates the United States’ performance as mediator. Graphic by Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Nora Berman

In my years as an editor on the opinion desk at the Forward, I’ve gotten dozens of emails from writers proclaiming that they’ve come up with the solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Their ideas are rarely original, or practical. Still, I can’t help but empathize with their desire to cut through this Gordian knot of history, violence, religion and land, and create something approaching peace.

There are, however, two people whose ideas on the conflict I am keenly interested in hearing about: Hussein Agha and Robert Malley.

The two have been intimately involved in trying to make peace between Israel and Palestinians for more than 30 years; Agha on the Palestinian negotiating team, and Malley with the Americans.

Their new book, Tomorrow Is Yesterday: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Peace in Israel/Palestine is a blistering, magisterial work of political and psychological insight that questions the viability of a two-state solution. Its most important message zeroes directly in on what most people avoid at all costs when discussing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: The fact that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is at heart a narrative clash. Most negotiators, diplomats and heads of state, they write, shy away from engaging with the seemingly irreconcilable emotions attached to the various stories of this land by each side.

While many, including Israel, were taken by surprise on Oct. 7, 2023, Agha and Malley see the terror attacks as “not the wave of the future but the past’s formidable revenge.” To focus on placing the blame for Oct. 7 solely on Hamas, or Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, would, in their eyes, be just another way of ignoring the enduring, brutal clash of stories at this conflict’s core.

At this time of hopelessness and desperation, the only hope of salvation, they argue, comes from finally being direct about the truth of the conflict. “A breakdown of this magnitude, so epic, a physical, human, and political wreckage this complete, can be redeeming,” they write.

‘The narrative issues’

In Agha and Malley’s view, the dueling histories of Israelis and Palestinians are the central problem in the region — and the peace process has repeatedly failed by seeking to avoid, in former President Bill Clinton’s words, “the narrative issues,” and instead focus on making a deal that only resolved the surface-level needs of both sides.

The Oslo Accords are their prime example. Did they aim to correct a historical wrong, the authors ask, or establish a settlement for the future?

The distinction might seem slight, but matters enormously. The Israeli side couldn’t accept a framework that suggested a historical wrong took place, because such a characterization would mean they committed horrendous crimes in the foundation of the state.

And Palestinians couldn’t sign on to a settlement that wasn’t based on the idea of such dealing with historical wrongs — because doing so could be seen as affirming that a simple settlement could have been reached in 1947; they would have had decades of statehood; and their years of bloody struggle were useless.

“If all that mattered was to find a place in which to live, not to recover a lost history and repair an injustice,” Agha and Malley write, “Palestinians might just as well be resettled elsewhere.”

Armchair critics of the peace process might castigate the Palestinians for rejecting past agreements, and Israelis for continuing to build settlements. Those are valid concerns, if all that mattered was making sure each side had land to live on.

But Agha and Malley make it clear that’s far from all that’s at stake. Israelis and Palestinians both deeply want the other side to acknowledge the truth of their stories: In Israel’s case, their historic connection to the land, and, for the Palestinians, the injustice and trauma of the Nakba. With that need in mind, past proposals for a two-state solution have been woefully inadequate. As Agha and Malley write, it is “impossible to solve the conflict in the present without pronouncing some judgement on its past.” The past means story, and stories are messy.

The problem of American involvement

No one escapes scrutiny in Tomorrow Is Yesterday, but the authors save their bitterest scorn for the United States.

“There were moments when a different outcome might have been possible,” Agha and Malley write — if the conflict had “a mediator with vision, nuanced understanding of the politics and psychology of the two sides.”

“Instead, it got a succession of ineffectual and bemused U.S. administrations,” they write.

In their view, the U.S. has — to this day — served as an overconfident, clumsy meddler in the region, overly accommodating of Israel and excessively prejudiced against Palestinians. Notably, the authors struggle to think of a single instance in 30 years when the U.S. actually put pressure on Israel “to take meaningful or sustained action it was determined to avoid.”

Part of the trouble: The superpower utterly neglected to engage with the history, ideology and psychologies of both sides. Instead, it believed tossing enough money and security assistance at the problem would suffice. They characterize the U.S. efforts over years of negotiations as overly focused on language and tit-for-tat exchanges of territory, and clumsily unaware of the narratives of each side’s national movement.

“To focus on appearances, written understandings, and verbal surfaces was a hallmark of U.S. diplomacy,” the authors write.

Most crucially, the full-throated American endorsement of the two-state solution as the only possible outcome only served to poison it as a real possibility. “It weaved fable after fable,” the authors write of the U.S., “about the inevitability of the two-state solution, its determination to achieve it, how close the parties were to reaching it, and proceeded to believe the fables it churned.”

In preaching that inevitability, the U.S. avoided engaging with those actors on both the Israeli and Palestinian sides — including Israeli settlers, religious Zionists, and Palestinians insistent on returning to the homes their families occupied before the Nakba — who are unsatisfied with the idea of partitioning the land.

That sidelining is understandable: Making peace is hard enough without factoring in religious Zionists who have a biblical desire for “Greater Israel,” or Palestinians who are not content with the idea of a state in Gaza and the West Bank. Yet these individuals form powerful factions in the region, and simply removing them from the conversation only makes the conversation, not the reality on the ground, less complex.

The future

Unlike many books about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Tomorrow Is Yesterday suggests ample possible solutions. Each option comes with serious problems to overcome, but challenges the prevailing wisdom that the two-state solution is the “only” solution.

One option: a joint entity of Jordanian-Palestinian confederation, in which Palestinian territories would be absorbed into Jordan with a Jordanian security presence on the borders. They argue that Israel has far more trust in Jordan than any Palestinian representative, and while Palestinians have developed a distinct political identity, Amman already serves as a Palestinian cultural hub. Under this proposal, Jordan would grow in size and influence, and Palestinians would gain political and economic power.

Above all, the authors reject the binary between one state or two-states as “unnecessarily constricted.” Alternative possibilities are two independent states with open borders, where civilians of each state can live anywhere they choose; a single, federated state in which each community is self-governing on matters of language and culture; or of “two superimposed states each covering the entire area” between the river and the sea.

I’ll be honest: I found some of these ideas increasingly far-fetched and difficult to picture. But Tomorrow Is Yesterday is exceptionally persuasive in its efforts to convince readers that a two-state solution only deals with the rational, when the conflict exists on both rational and emotional planes. Neglecting the grief, pride and painful emotions behind each side’s stories will only perpetuate a series of ceasefires and wars that achieve, in the longterm, nothing.

At this point, what is the harm in thinking outside of the rigid nation-state box?

Practically, not much can change until the war in Gaza ends, which may be one reason behind Netanyahu’s determination to keep it going. Some of his his far-right allies have repeatedly expressed their desire for a full population transfer of Palestinians out of Gaza, and for Israel to annex both the Strip and the West Bank.

Yet, if we are all trapped in this awful state of affairs, it is worthwhile to examine the true narratives of each side and the outlook they contain for the future. Because, in the end, this conflict isn’t really about land, but about people. They deserve an honest reckoning.