The Jesse Jackson I knew didn’t just repent toward Jews — he became a hero for us

I knew the late reverend for decades, and saw firsthand his willingness to change, grow and reach across the divide

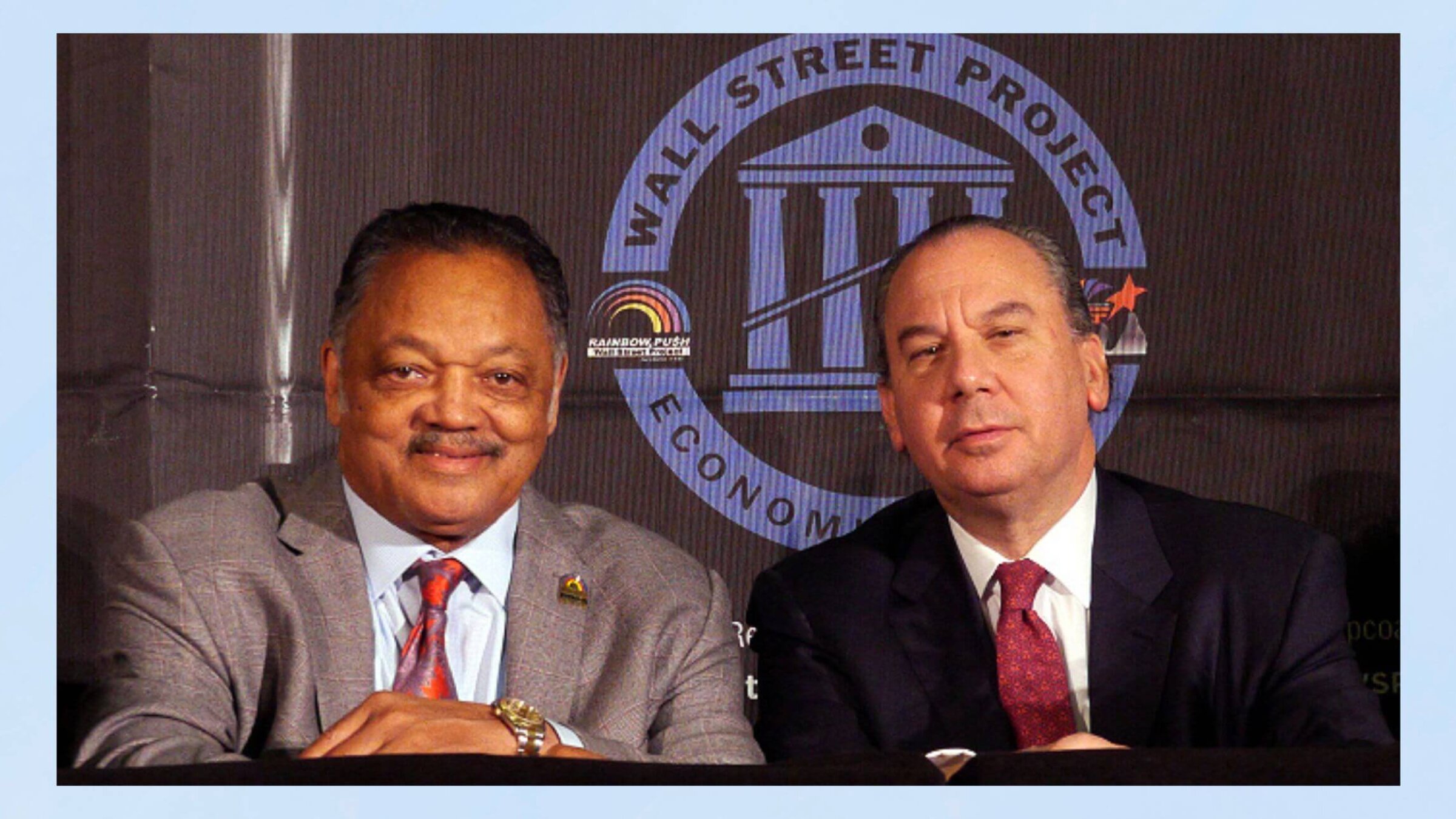

Reverend Jesse Jackson and Rabbi Marc Schneier. Photo by Gerald Peart

I know that for many in our community, the name of Reverend Jesse Jackson evokes a complicated history. Yet when I received the news of Jackson’s passing on Tuesday, I did not just mourn a global icon of the Civil Rights movement. I mourned a cherished friend.

Over the course of more than three decades, Jackson and I marched together, prayed together and worked tirelessly to repair and renew the historic alliance between the Black and Jewish communities.

When I first met him at an MLK Day reception for Black and Jewish leaders in the early 1990s,the silence between our communities was not merely awkward, it was deafening. There had been a painful rupture between Jackson and the Jewish people in the 1980s, following remarks he made, including calling New York City “Hymietown” during his 1984 presidential campaign. And following the 1991 Crown Heights riots, the wounds in the Black-Jewish alliance were real.

But I believed then, as I believe now, that true leadership is not about speaking to your friends. It is about navigating the hard road of reconciliation with those from whom you have drifted apart.

Jackson proved to be a partner of immense courage. He understood that the “shared dreams” of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel could not survive on nostalgia alone. Alliances must be nurtured. Trust must be rebuilt. And he was willing to do that work.

I was honored to help him as he did. Over years of quiet dinners and candid conversations, we built a trust through our shared spiritual connection that made public healing possible. That work culminated in November 1999, in an event that in the tensest moments between our communities might have appeared unimaginable: I welcomed Jackson to the main campus of Yeshiva University, the flagship institution of Modern Orthodoxy, to keynote a groundbreaking conference on Black-Jewish relations, sponsored by the Foundation For Ethnic Understanding.

Standing at that podium, facing a room of future rabbis and Jewish leaders, Jackson did not merely speak; he reconnected. Also, in 1999, when 13 Iranian Jews were arrested and charged as Zionist spies, Jackson committed himself to working for their release. It was a moment of a profound teshuvah and mutual embrace. It signaled the beginning of a new era of connection.

From that day forward, he never wavered. For decades, he remained a steadfast friend to the Jewish people. Our connection moved beyond just “interfaith dialogue,” which can often be nothing more than an exchange of pleasantries, and into the realm of shared struggle. Every January for two decades, I had the honor of serving as a keynote speaker at his Wall Street Project Economic Summit in New York City, which brought together some 1,000 Black ministers from all over the country to empower the Black community economically.

Black and Jewish communities share a history of persecution, with both experiencing systematic oppression. Jackson understood that you cannot fight antisemitism without fighting racism, and you cannot have civil rights without economic rights. He taught me that we are bound by a common faith and a common fate.

I will never forget calling him in 2017, shortly after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, to wish him strength. He said to me, “Rabbi, I’m waiting for your brothers…” and then he immediately stopped and corrected himself. “No, our brothers, to come up with a cure.” In that moment of vulnerability, the distance was gone. He didn’t just see the Jewish people as political allies; he counted on us as family.

In Jewish tradition, we are taught that a hero is one who turns an enemy into a friend. Jesse Jackson was a hero not because he was perfect, but because he was willing to change, to grow, and to reach across the divide.

The bridge we built together is strong. Now, it is up to the next generation to walk across it.

May his memory be a blessing.