Nabokov’s Dystopic ‘Bend Sinister’ Turns 65

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It’s hard to imagine Vladimir Nabokov as a commercial failure. Yet that was precisely what happened with his second English-language work, the nightmarish and satirical dystopian novel “Bend Sinister,” which celebrates its 65th anniversary today. Originally titled “The Person from Porlock,” then “Game to Gunm[etal]” and later “Solus Rex,” “Bend Sinister” was Nabokov’s first novel composed in the United States, and was published by Henry Holt and Company. But it received only lackluster promotional treatment after the departure of Allen Tate, the only staff member at Henry Holt who admired the book.

“Bend Sinister” follows Adam Krug, a world-famous philosopher living under a newly formed totalitarian regime in a vaguely Central European country. The recently widowed Krug ignores repeated demands to acquiescence from the nascent dictatorship and its leader, Paduk, a former classmate whom Krug used to bully and refer to belittlingly as “Toad.” As a means of persuading Krug to validate the regime, Paduk’s henchmen abduct his colleagues and friends and shut down the university. Krug finally submits when the government seizes his 8-year-old son, David. But when a bureaucratic error leads to David’s accidental death, Krug defies his captors and, in a brilliant finish, succumbs to his inevitable death after realizing that he is merely a figment of the author’s imagination.

It didn’t help the book’s success that it garnered mostly mediocre to outright negative reviews upon its release. The New Republic praised its fluent prose — which “belies its author’s comparative unfamiliarity with the language” — while disparaging Nabokov’s “apparent fascination with his own linguistic achievement.” Diana Trilling published a notoriously scathing write-up in The Nation two days after its release, arguing that “what looks like a highly charged sensibility in Mr. Nabokov’s style is only fanciness, forced imagery, and deafness to the music of the English language, just as what looks like innovation in method is already its own kind of sterile convention.”

Not surprisingly, then, “Bend Sinister” remains one of Nabokov’s most neglected works, by both critics and readers. Indeed, compared to more distinguished novels like “Lolita” and “Pale Fire” Nabokov’s indulgent awareness of his own rhetorical dexterity here manifests itself in overly convoluted digressions that dilute an otherwise masterful story.

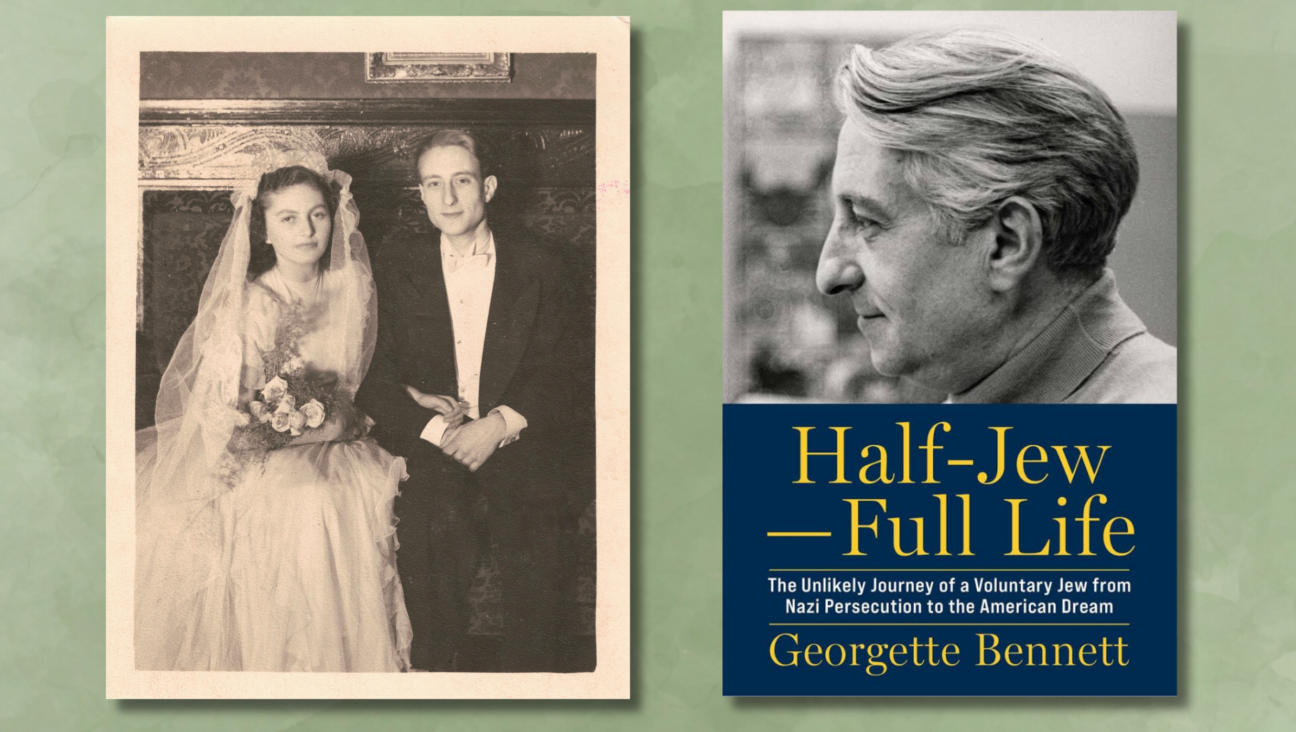

This is doubly unfortunate given the rich biographical history from which “Bend Sinister” emerged, especially the author’s personal encounters with anti-Semitism. Nabokov was raised by a father who stridently opposed anti-Semitism in pre-1917 Russia, and in 1925 he married a Jewish woman, Véra Slonim, with whom he raised a son in 1930s Germany. As an intensifying anti-Semitic environment cost Véra her job and put Nabokov’s career in jeopardy, they first moved to France and later fled to New York as Hitler’s troops marched on Paris. Even in America, Nabokov frequently encountered anti-Jewish sentiment, with one Russian professor at Columbia lamenting, “All one hears here are Yids.”

With this in mind, it’s hard to ignore the parallel between Krug’s dead wife and son and Nabokov’s personal unease. And it’s fitting that “Bend Sinister” celebrates this milestone amidst a resurgence of European extremist political factions. The Golden Dawn party of Greece, a neo-Nazi group, made headlines last week when a spokesman attacked two left-wing politicians on live television, and Marton Gyongyosi, a member of the far-right and anti-democratic Jobbik party of Hungary, recently said that Israel’s “Nazi system” strips Jews of the right to talk about World War II.

“Bend Sinister,” for all its shortcomings, evinces an unnerving prescience that reminds us of our proximity to a darker past, but also our ability to overcome it. It is one of Nabokov’s finest statements on the fight to reclaim freedom and individualism against the pressures of mass culture and victimization.