Getting Sick of Sondheim?

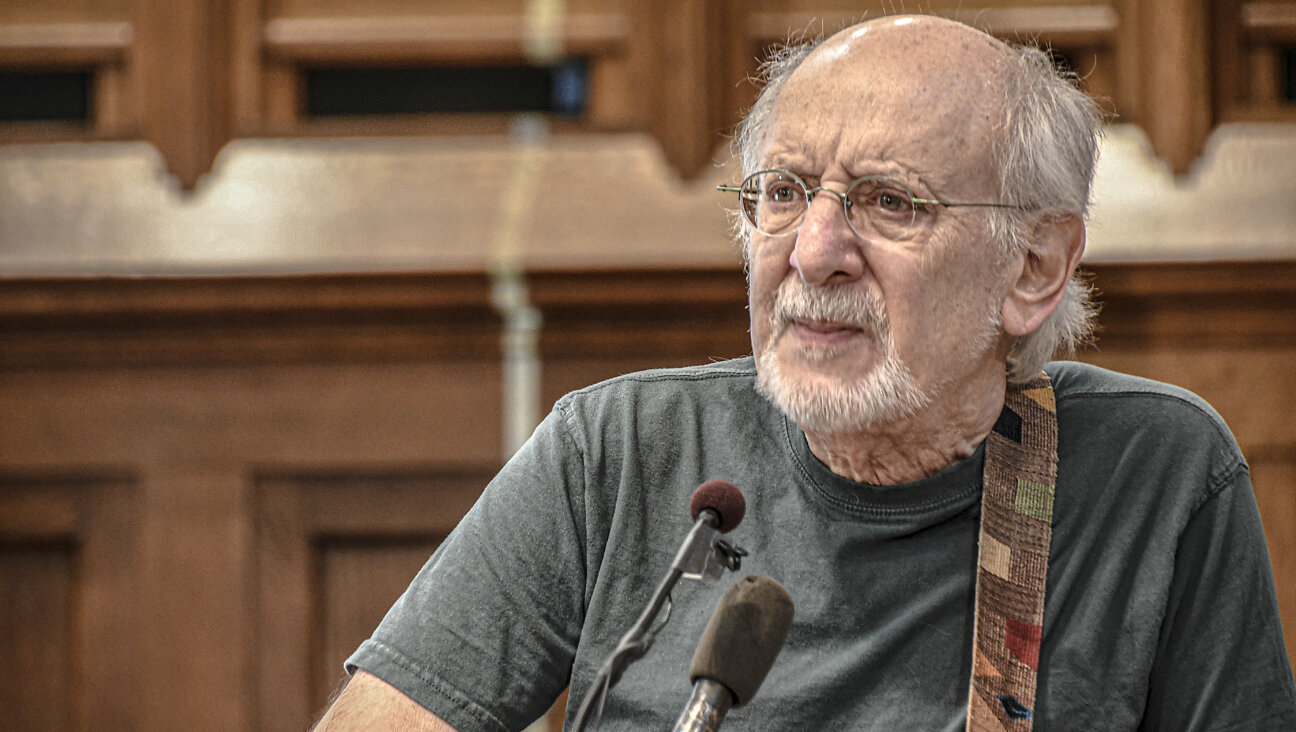

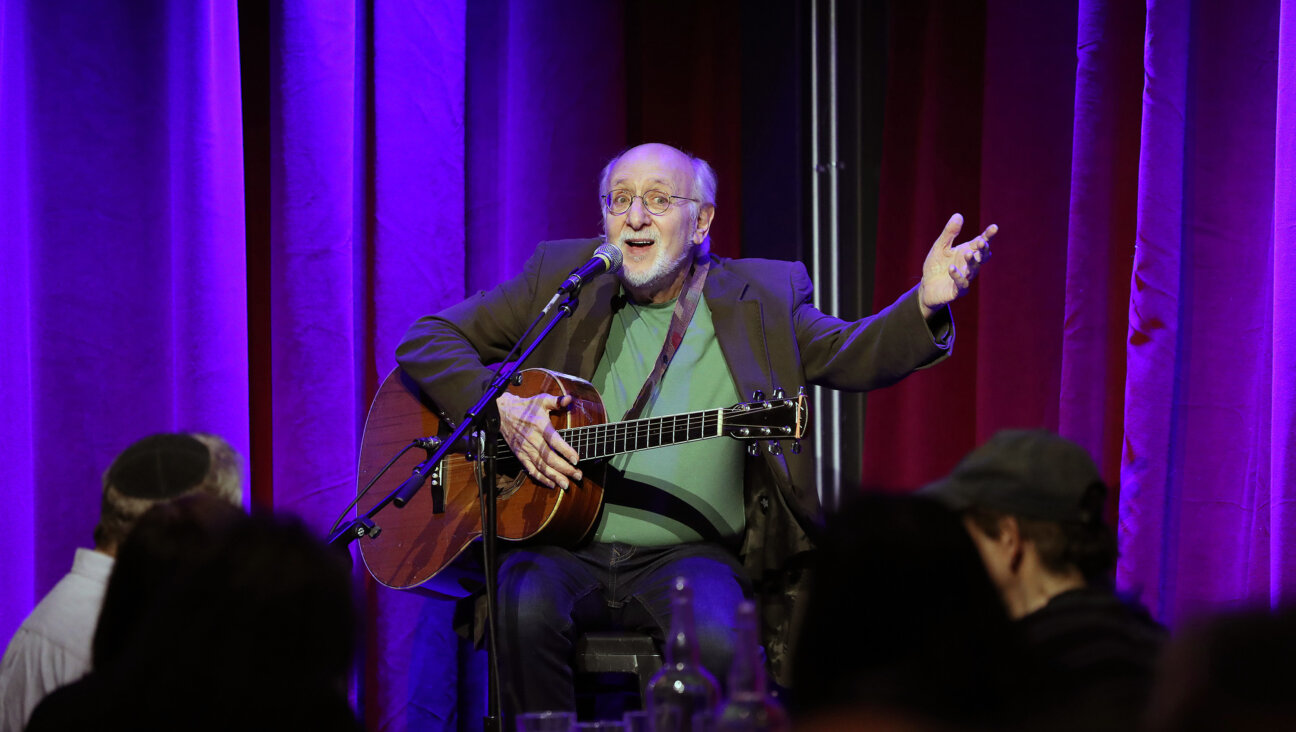

Black Tie To Match His Comedy: Stephen Sondheim moves into his sixth decade of darkly witty musicals. Image by GETTY IMAGES

‘But who needs Albert Schweitzer/When the lights are low?” (“Follies”) “Perpetual sunset is/Rather an unsettling thing.” (“A Little Night Music”) Who else but masterful Broadway lyricist and composer Stephen Sondheim, who turns 80 on March 22, would have found those rhymes? It’s only fitting that all-star celebrations should be plentiful, like the New York Philharmonic’s March 15–16 “Sondheim: The Birthday Concert”, followed by the musical revue “Sondheim on Sondheim,” which begins previews March 19 at Studio 54 and runs from April 22 to June 13. Sondheim was expected to give a public chat March 4 about his work at Chicago’s Harris Theater, and following that, the galas are multiplying, including April 26 at New York’s City Center; the NSO Pops, May 6–8 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and many others.

Black Tie To Match His Comedy: Stephen Sondheim moves into his sixth decade of darkly witty musicals. Image by GETTY IMAGES

The question that arises, though, is whether the gala revue format is genuinely suited to Sondheim, a musical tragedian whose dark imagination regularly hovers over a murderous void (“Sweeney Todd,” “Assassins”)? The very notion of a peppy Sondheim musical revue is somewhat like seeing Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” performed by the Ice Capades.

Such is the conclusion of erudite Broadway historian and Sondheim buff Steven Suskin, in the new fourth edition of his definitive “Show Tunes: The Songs, Shows, and Careers of Broadway’s Major Composers.” Suskin points out that in the legendary Sondheim musicals “Company” (1970); “A Little Night Music” (1973); “Pacific Overtures” (1976) and “Passion” (1994), “words and music reveal character in a highly personal, self-analytical way.” Past revues merely presenting collections of Sondheim melodies, like “Putting It Together” (1993 and 1999), tend to “trivialize rather than celebrate the Sondheim songs.” Divorcing Sondheim’s music from its dramatic context deprives audiences of an essential element of his genius, which may be why splendid actors who are also able to put across a song, like Angela Lansbury, Len Cariou, and Judi Dench, have always been quintessential Sondheim interpreters.

The above reference to Beckett is not merely serendipitous. A 2008 study from Ohio State University Press, “The Theatre of the Real: Yeats, Beckett and Sondheim” by Gina Masucci MacKenzie, somberly links these two apparently disparate creators as simultaneously expressing “radical pleasure and pain.”

Unlike Beckett (or Yeats, for that matter), Sondheim has been inspired by famous or career criminals, like the eponyms of “Assassins” and “Sweeney Todd,” or the swindlers in a failed show variously revised and retitled “Wise Guys” (1999), then “Bounce” (2003) and finally “Road Show” (2008). Much earlier, Sondheim’s lyrical inspiration was lavished on the soundtrack of Alain Resnais’s 1974 film, “Stavisky,” about French-Jewish swindler Alexandre Stavisky. Even before this, Sondheim’s lyrics (to the music of Jule Styne) for the ferocious stage mother Mama Rose in 1959’s “Gypsy” were apparently inspired by yet another Jewish villain, his own mother, Janet “Foxy” Fox Sondheim, his hatred for whom Sondheim has confided to journalists and biographers. A plausible essay, “Psychopathic Characters on the Stage of Stephen Sondheim” by Matthew Isaac Cohen and Phyllis M. Cohen, [published]( Yale University Press; 2007; http://yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks/book.asp?isbn=9780300119961 ‘published’) in “The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, v. 61” (Yale University Press, 2007), makes the link between Sondheim’s creative obsession with villains and his hatred for his own mother crystal clear. Obsessive detestation of life-giving Foxy leads to creative obsession with other villains, con men, cutthroats, etc. QED, Dr. Freud!

Yet despite loathing home and Mother, Sondheim has paradoxically embraced his Jewish heritage, even introducing a then-revolutionary Yiddishism into the strippers’ song from “Gypsy”: “Once I was a schleppa/Now I’m Miss Mazeppa.” Curiously, the Jewish popular song parodist Allan Sherman decided that Sondheim’s “Gypsy” lyrics were not explicitly Jewish enough, and on one of his 1960s song albums, Sherman rewrote the song “Small World,” which in the original goes, “We could pool our resources/By joining forces from now on” to read instead, “Darling, let’s say a brocha/And be mishpocha from now on.”

Never genuinely needing this kind of rewrite, Sondheim constantly makes self-defining declarations like, “I’m just a nice Jewish boy from the 19th century,” or, “all nice Jewish boys studied the piano,” in which the only word meant ironically is “nice.” Sondheim’s lyrics were included in the 2009 Siddur B’chol L’vav’cha of Congregation Beth Simchat Torah (“Founded in 1973 by forward thinking gay Jews” — order your deluxe leatherbound edition here. Sondheim has likewise long enjoyed cult status in [Israel]( (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfn6p5hHksM ‘Israel’) with such performers as Limor Shapira and Tsviki Levin performing his works. And for its Purim shpiel this year, Portland’s Congregation Beth Israel sensibly programmed a performance of [“Sweeney Todd.”]( (http://www.jewishreview.org/node/12142 ‘“Sweeney Todd.”’)

Even Sondheim works not ostensibly inspired by Judaism turn out to have Jewish roots, like the musical “Into the Woods” (1987), an elaboration on Grimm’s Fairy Tales that owes much to Bruno Bettelheim’s controversial 1976 Freudian study, “The Uses of Enchantment.” An Austrian-Jewish survivor of Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, Bettelheim, nicknamed “Brutalheim” by his detractors, applied Freudian analysis to fairy tales, describing the huntsman cutting open the wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood” as “rebirth” (although not for the wolf).

Still, among some American Jewish colleagues, Sondheim has not enjoyed constant, unqualified admiration. Musicologist Steve Swayne’s “How Sondheim Found His Sound” brilliantly and lovingly analyzes the composer’s varied sources of inspiration, both direct and indirect. Less affectionately, a fellow songwriter, Fred Silver (1936–2009), composed the wry ditty “I’m Getting Sick of Sondheim,” ), which plays on the sheer omnipresence of Sondheim’s work as performed by every imaginable actor, however unmusical or unrehearsed. Silver would readily offer demonstrations of how Sondheim’s musical magpie approach borrows lyrical ideas from many composers — much as Swayne did, but far less reverently.

It may be that Sondheim’s most profound talent is as a parodist, both in words and in music. His deflating wit punctures pretensions as did that of Sherman and, even more so, Tom Lehrer who, like Sondheim, embraced unexpected lyrical subjects, from the Vatican to Wernher von Braun to please the punters. Like Lehrer, who attended the same boyhood summer camp as Sondheim in 1930s New York, Sondheim has a sometimes gratingly contrarian, firebrand approach, which makes his talent stand out all the more. Despite recent public appearances where Sondheim is all gracious smiles to please the punters, as if adopting a genial, albeit grizzled, Gabby Hayes-like persona, the real Sondheim will surely emerge after all the birthday hoopla dies down.

Fans of Broadway gossip are holding their collective breath until October, when Knopf publishes Sondheim’s “Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes,” sure to be a landslide of pitiless sarcasm from the heart. After all, Sondheim has proved that on the Broadway musical stage, snarky payback and murderous hatred can make for a brilliantly unique career.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

Watch Zarah Leander, the 1930s Swedish singer who compromised herself by making films in Nazi Germany, perform “Send In The Clowns” in a 1978 German version sinister enough even for Sondheim, below:

[12]: Yale University Press; 2007; http://yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks/book.asp?isbn=9780300119961

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO