The Water Carrier

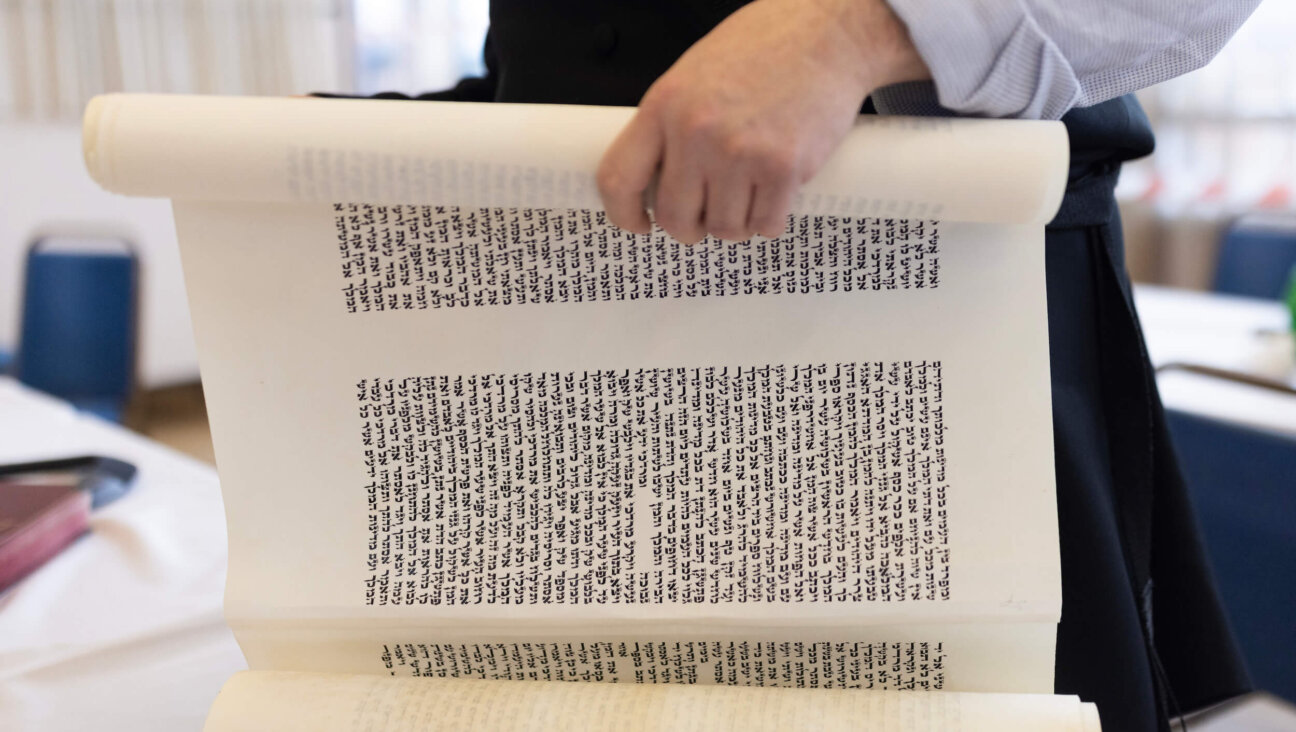

Take No Prisoners: A photograph of the author?s grandmother, Fradl, who was jailed in 1906.

Renowned scholar David G. Roskies is the Sol and Evelyn Henkind chair in Yiddish literature and culture at the Jewish Theological Seminary. The following excerpt is from his forthcoming memoir, “Yiddishlands” (Wayne State University Press). In the work, Roskies discusses his life and the life of his mother, and explores the Yiddish experience and historical events of the last century.

Take No Prisoners: A photograph of the author?s grandmother, Fradl, who was jailed in 1906.

Uncle Grisha’s table, laden with fruit, jam and tea — the late-night crowd didn’t drink; never used any external, artificial means of stimulation — was a place for songfest and protest. Vilna, after all, had been the birthplace (in 1897) of the Jewish Labor Bund of Russia and Poland, and some of its founding members, like Anna Rosenthal, still marched at the head of every May Day rally. Only those whom Mother and her circle protested against were not the class enemy from without but the Jewish enemy from within. This she explained to my friend Michael Stanislawski, who was hired to interview her on behalf of a research project, Yiddish Folksong in Its Social Context. Poland of the 1920s, she contended, was rife with Jewish self-hatred — with what she called kompleksn, neuroses — and the best way to fight back was by means of parodic Yiddish songs.

No set of interviews was ever conducted so effortlessly. He visited Mother 12 times, never left without being fed; if Xenia wasn’t cooking, even anchovy sandwiches counted for a meal. And only in the middle of session 12 did he remember to fill in the analytic questionnaire with her name, place of birth, years of schooling, etc., for could anyone imagine a single informant recording 127 songs in six languages — Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian and one song in Romany — heard when she was 8 from a beggar in the courtyard of Zawalna 28/30?

Those that she called her “Bundist” songs were the naughtiest — and most interactive, like “In a Shtetl Not Far From Here,” an anti-Hasidic number punctuated by the assembly adding “oy” at the end of each line, and with a chorus half in Yiddish and half in Polish.

In a shtetl not far from here, (oy)

there lives a little Rebbe dear. (oy)

A living he makes not by doing miracles, (oy)

but from his dumb Hasidic animals (oy-oy-oy)!

In the next stanza, when the rebbe’s son is caught behind the bushes with a shiksa, he attempts to justify himself with a last-minute defense:

Daddy, daddy, don’t you fret (oy),

a shiksa is kosher, you bet (oy).

Our son will grow up a Talmud scholar, yet, (oy)

the good Lord be blessed! (oy-oy-oy)

Real Bundist songs — about the overthrow of the tsar, or seamstresses slaving away at the workbench — she almost never sang, although she harbored certain sympathies for the poor and downtrodden. To begin with, there was an orphanage in her courtyard on Zawalna 28/30, and she sometimes overheard the children playing and singing in Yiddish. During summer vacations, she hung out with the kneytsherkes, the women who fed the reams of paper through the folding machine at the press, and so enjoyed listening to their stories and songs that during their lunch break, when they sent out someone for herring, radishes and strawberries, she ordered the same menu from the cook and ate alongside them.

If these sympathies did not extend to Bundists per se — and here we leave the researcher of Yiddish song, armed with his Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder, and revert back to more primitive means of biographical study — it was because of what they did to my grandmother Fradl in the summer of 1906, a time of revolutionary upheaval, when she was carrying Mother in her womb. Fradl was at the Rom Press on business, when someone rushed in to say that a group of Bundist agitators had just tried to publish illegal proclamations but were stopped from doing so by the foreman. Most certainly they were heading next for the Matz Publishing House. Sure enough, by the time Fradl got there — it was a good 20-minute walk for a woman in her condition — the printing presses had been requisitioned, every worker had been pressed into service and a young man brandishing a pistol was in charge. Within the hour, the press was raided by the police, and everyone made a run for it by jumping through the ground-floor window. The only one who stood by Fradl, who obviously couldn’t run anywhere, was Moyshe Kamermakher, as loyal to her as a son, having spent his whole life at the press. The two of them were hauled off to the Lukishki Prison, where the most hardened criminals and political prisoners were kept. Fradl was in mortal terror. But along the way, they ran into a water carrier mit fule emers, his buckets overflowing with water, which Fradl knew was the best of omens. How the buckets are wasted on me, she thought, now that I am being imprisoned for life. But the police had made such a clean sweep of the revolutionary underground that every cell at the huge Lukishki complex was already filled to capacity. So Fradl and Kamermakher were dragged off to the central police station, where, for a few groschen, they were provided with pillows and blankets. But days turned to weeks, and Fradl despaired.

Meanwhile, her husband, Yisroel, had sent word of her arrest to her niece, Naomi, who ran Syrkin’s Bookstore in St. Petersburg. This young woman came running to the governor of the Vilna region, who was both her customer and her personal friend, to appeal on behalf of her aunt. Imagine — he was so taken with Naomi that he looked into the matter himself, found Fradl’s file in the relevant office for internal security and destroyed it.

“Tell your aunt,” he said, “that she has you to thank for her life, because in the present political crisis, she probably would have died in prison before her case ever came to trial.”

Fradl was freed, but she made her own release conditional on that of Kamermakher, her most loyal worker. The whole experience cost her two of her front teeth, which fell out from either fear or despair, and Masha, growing up, was surprised to see that her mother, so beautiful and perfect, was missing two of her teeth; that’s how she found out about her mother’s arrest and about Kamermakher, whose loyalty and love Fradl reciprocated. Fradl modeled the greatest possible respect for her workers, whom she would invite to the table whenever they came to the house on business, serving them tea from the samovar, with preserves, and sometimes with beer, such that long before the revolution, Fradl made no distinction between herself and her workers. How natural, then, for Masha to befriend the kneytsherkes in her mother’s press and to eat what they ate, a practice she continued even in Canada, for whenever Palmer Hart came from Huntingdon to do odd jobs around the house, she would serve him the same meal she served us, veal chops and mashed potatoes, which even with his one hand he could eat as deftly as we can with two.

Still, there was no love lost for the Bund. One day, Masha was out taking a walk in Saint-Sauveur, where every summer the Montreal Yiddish colony rented bungalows. She bumped into Shloyme Abramson, a leader of the Warsaw Bund who escaped on the Gerer rebbe’s special train, and he introduced her to a former comrade named Shloyme-Fayvish Gilinsky.

“Meet Masha Roskies,” Abramson said. “She’s from Vilna.” “Vilna,” Gilinsky said with a smile, “that was my very first assignment. The Central Committee sent me there to print up some Yiddish proclamations. Just as I took over the Matz Press, the boss rushed in and I stopped her at gunpoint.”

“The boss?” Mother asked. “Whom do you mean?”

“Fradl Matz,” he said. “The gun was loaded, and I held it to her head until the job was done. Those Jewish bandits, you know, I had to stop her from screaming, and she kept fainting anyway. That’s how much I managed to scare her, though I would never have pulled the trigger.”

Mother shot Gilinsky a venomous look and continued on her way.

When Mother read his obituary in the Jewish Daily Forward, she threw a fit.

“He nearly killed my mother,” she yelled. “Nearly killed me, for that matter, in utero. Some hero! The real hero was my mother, and Moyshe Kamermakher, and the lone water carrier, her lamed-vovnik, her hidden saint.”

© David G. Roskies 2008.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO