David’s the Singer, He’s the Rapper

Oded Turgeman, director of the new short film “Song of David,” doesn’t do things the easy way.

As a burgeoning film director, he applied to Jerusalem’s most prestigious film school, with a commander in a combat unit as his only prior life experience. Then he moved to America to attend the American Film Institute —the first Orthodox Jew ever to enroll there — and, because of his Sabbath observance, had to shoot and produce each of his four thesis films in two days, not the usual three.

And when the deadline for AFI’s short-film contest was two weeks away — this was the night before Passover 2006 — and most applicants had worked on their proposals for months, Turgeman was struck with inspiration for the film that would, nearly two years later, become “Song of David.”

“It was accepted by the committee,” Turgeman said, laughing. “It was an impossible thing, but they accepted it.”

He secured a shooting location in Los Angeles’s Yeshiva Or Elchonon and a star in the rapper Niz (real name: Nosson Zand), who flew out to Los Angeles to meet Turgeman. Despite his lack of experience (truly: Zand had never acted before), Turgeman was immediately convinced he was the right Hasid for the part. For Niz, a baal teshuvah who had only been Orthodox for only a few years, landing the role of David was a coup. “I tell people that David is a yeshiva bokher who wants to be a rapper, whereas I am a rapper who wants to be a yeshiva bokher,” he said.

As for the film itself, it would be tempting to describe “Song of David” as a straight-up Orthodox hip-hop movie, if such a thing existed. The truth is, it’s much more complicated. The film is a study of its titular character’s struggle: the struggle to be a good Jew and a good artist.

From the start, the movie dwells firmly in iconic imagery. The opening credits fade from black into the striking blue water of a ritual bath, with a man in his early 20s dunking himself beneath the water. From there, the film places Niz in terse, bleak scenes, light on words and heavy with intended meaning, of David being scorned by other yeshiva students, of him standing on the yeshiva rooftop and writing verses.

The paradigm of David’s character — a Hasidic Jew who can find solace only in hip-hop music — is hardly a unique occurrence in today’s real-life Hasidic world, where professional masters of ceremonies like Y-Love and Matisyahu use music as a way of both self-expression and proselytization, and bands that sound like MTV clones play to packed auditoriums of single-sex audiences.

But the clash of hip-hop and Hasidic cultures is still such a striking study in oppositions, especially to non-Orthodox audiences, that the film is almost forced to traffic in these stark, hard-hitting images in order to get through to the audience: the black-and-white clothes, the bearded face nodding in time to rhymes, the traditional wordless niggun hummed over vocal beatboxing. (The film’s soundtrack features Ta-Shma, a hip-hop duo based in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights who contribute both original songs and music from their 2006 album, “Come Listen.”)

To shoot the film, Turgeman had to wait nearly a full year, until Passover 2007 — the only time that the yeshiva was out of session. “The catering alone was a nightmare,” Turgeman recalled. “Even though 95% of the crew was not Jewish, all the food had to be Kehila kosher. And it was a week before Passover. It was really tough. But we withstood it.”

In order to meet with the yeshiva’s demands, all the women on the set had to wear skirts, and married women, even non-Jewish ones, were asked to cover their hair. But those restrictions were easy compared with the ones imposed by the film’s star. After becoming Orthodox and going through the yeshiva system himself, Niz was wary of getting involved in any sort of film, especially one in which he’s first seen underwater and shirtless inside a ritual bath. To film that scene, all female crew members were asked to leave the room, including the cinematographer.

“The [bath] shot was one of the more questionable moments that I encountered,” Niz said, although “eventually, the scene gained the approval of a local rabbi whom I both trust and respect.”

With production completed, Turgeman is now taking the film on a festival tour. This month, “David” had its Los Angeles premiere, as well as a screening at the prestigious AFI Dallas International Film Festival, one of the preliminary screenings that leads to Oscar qualification. Turgeman and his screenwriter are working on a full-length adaptation.

In the meantime, though, Niz is back to his first love, hip-hop. “I don’t know if I’d act in another film,” he said. “I believe as a Jew that many things in this world can be used for both good and bad. I viewed this movie as an opportunity to spiritually elevate the film industry.”

Watch a clip from “Song of David” below:

Matthue Roth is a performance poet and novelist. His most recent book, “Candy in Action” (Soft Skull Press/Red Rattle Books, 2007) is about a girl being stalked who just happens to be a kung-fu master. He also raps on the book’s soundtrack at www.candyinaction.com.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

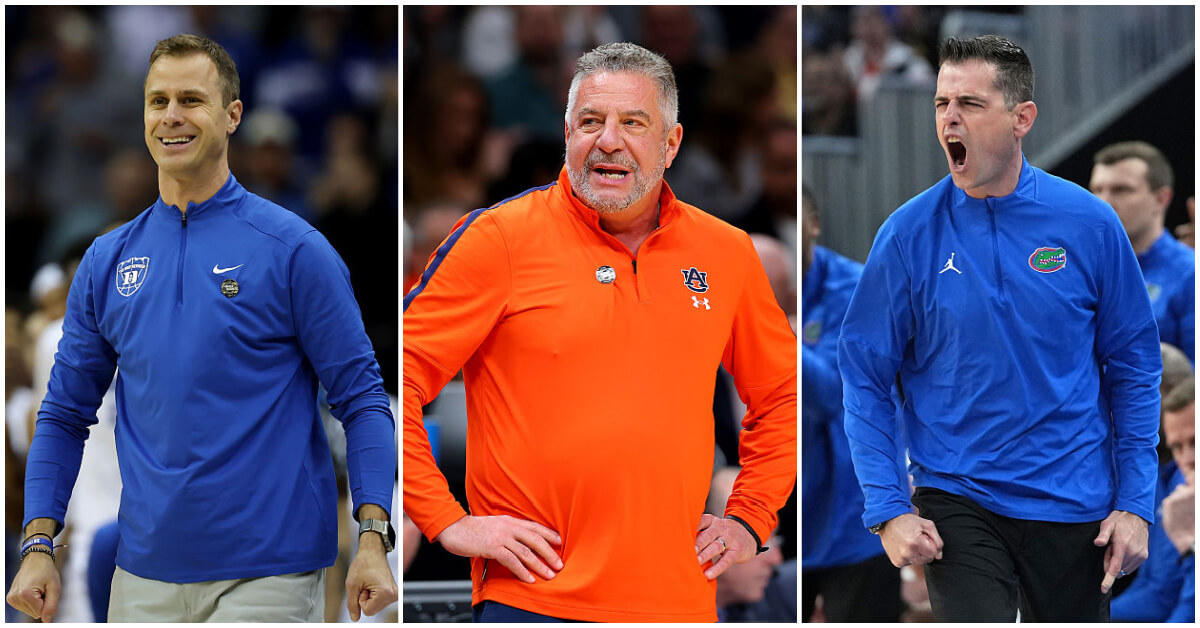

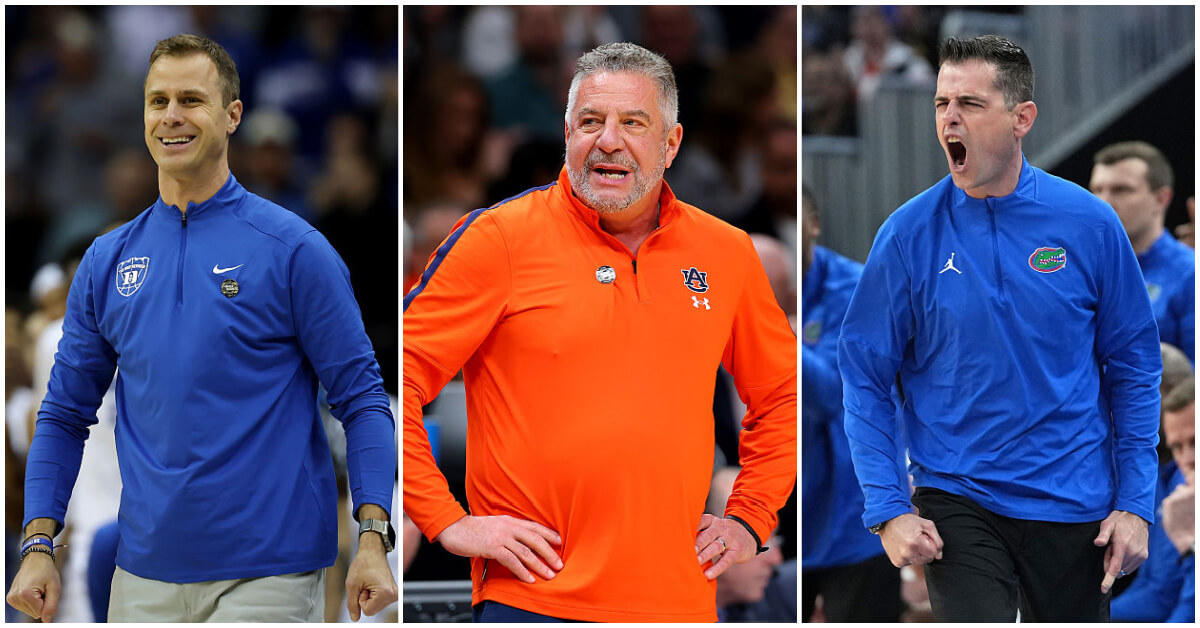

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 4

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

In Case You Missed It

-

Books The White House Seder started in a Pennsylvania basement. Its legacy lives on.

-

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

-

Fast Forward Yarden Bibas says ‘I am here because of Trump’ and pleads with him to stop the Gaza war

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.