Troubled Birthplace of the Torah

Image by getty images

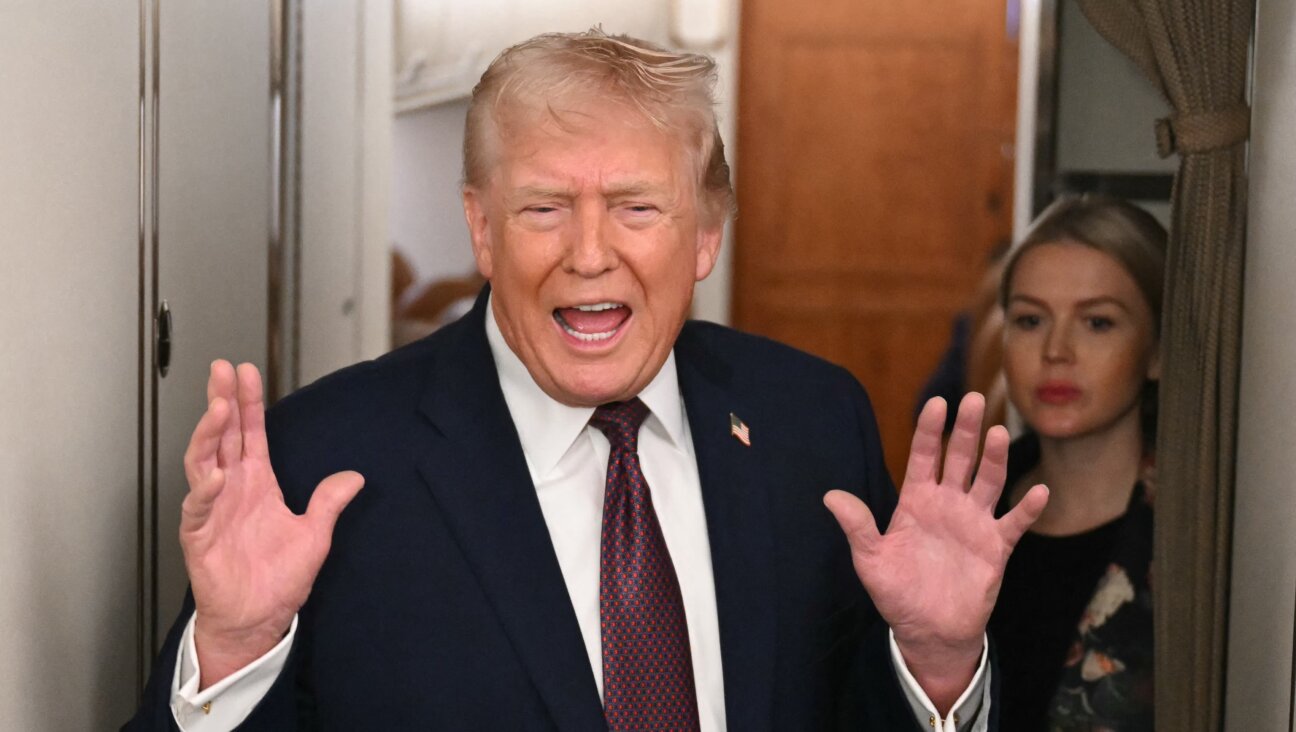

Stark and Lawless Land: The Sinai Desert was once a vacation spot for Israelis. It is turning into a fullblown battleground between Bedouins and Egyptians. Image by getty images

The Sinai, where fire once shot into the heavens while Moses vanished in a thicket of clouds, is once again ablaze.

This Shavuot, the wilderness where morality was made law, is a fountainhead of lawlessness and strife, a microcosm of the Arab world’s ailments and a source of Israeli perplexity.

We Israelis know the Sinai better than any of our forebears since Moses. Having fought, served, hiked and vacationed there, we fell in love with the majestic moonscape where purple mountains and bronzy cliffs overlook golden dunes and azure reefs.

Following its return to Egypt, Israelis thronged every holiday to Sinai’s beaches, canyons and resorts. The long lines of vehicles in Eilat — where passports bearing the Jewish menorah were stamped with an Egyptian eagle, and vehicles with a little Israeli flag on their license plates were waved through an unassuming border crossing almost as naturally as one proceeds to Quebec from Vermont— were to us sweeter than any military victory.

Now, most of this is nostalgia.

What began in the 2000s with a slew of terror bombings in resorts along the Red Sea shore has since become a wholesale offensive on Egyptian authority, including raids on police stations, postal trucks and roadside checkpoints; harassments of the Sinai’s peacekeeping force, and attacks on the pipeline that exports gas to Jordan and Israel.

The Jewish state is, of course, a victim of the mayhem in Sinai, but its origins stem not from a conflict between Arabs and Jews, but from one between Arabs and Arabs.

More than half of the Sinai’s 400,000 inhabitants are Bedouin, semi-nomads who wander between oases while riding camels and herding sheep. When Egypt finally regained the Sinai in its entirety in 1982, the Bedouins soon learned two things: First, Cairo had great plans for the region, and second, there was nothing in it for them.

The great plan was a Red Sea Riviera, which the Egyptians indeed built, planting more than 100 resorts along 120 miles of turquoise shoreline where 5 million tourists arrived annually.

Alas, it all happened without the Bedouins. They were told to take to the mountains, where they became 90% unemployed. Watching from there as the Mubarak regime’s officials and their cronies took over the shoreline where they had been grazing for centuries, the Bedouin conclusion was simple: Cairo is the enemy.

And while Cairo humiliated them, someone else took note over the past few years: Al Qaeda. The Bedouins, ordinarily calm, hospitable and mildly religious, now lent an ear to foreign Islamists who arrived in their midst to tell them that the Riviera, besides abusing the Sinai’s indigenous inhabitants, is also religiously profane and worthy of the terror it soon faced with Bedouin involvement.

The region became a repository of hatred, encapsulating all the fixtures of Arab discontent: political corruption, social alienation, tribal abuse and fundamentalist opportunism.

These days, a falcon hovering above Mount Sinai can see the Bedouin revolt’s damage all around: in the east, half-empty Red Sea beaches and idle construction sites; in the northwest, blasted pipelines; east of there, smugglers handling machine guns, rockets, and missiles, and along the Sinai’s eastern flank, a new, nearly completed, 150-mile Israeli fence built to block the smuggled fruits of lawlessness — drugs, prostitutes and illegal migrants.

In ancient times, countless Near Eastern armies crossed the northern Sinai as they stormed each other’s empires. The nomads of the day made sure to follow those military expeditions from the safety of the mountains south of the Mediterranean coastline, where they could assess one power’s chances to rise and another’s to fall.

Now, like those ancient nomads watching through clouds of sand the passage of empires, and like the Bedouins watching through tears their robbed shoreline, we Israelis are watching through our fence how our wellspring of peace wilts in the Arab Spring’s heat.

In Cairo, presidential candidates promise to create Bedouin jobs within a remodeled Sinai police force and in a new Sinai-Gaza free-trade zone. Israelis have no illusions about the next Egyptian leader attracting them back the Sinai’s beaches, but they do hope he will at least deliver on his promises to its dwellers and restore their honor.

On Shavuot, Jews recall not Pharaoh, the despot who drowned off the Sinai’s shores, but the rest of his era’s kings. That royal multitude, according to the Talmud, was actually inspired by the Israelite lawgiver’s deeds, so much so that when Moses received the Torah, they ”trembled in their palaces and recited poetry.”

No one is asking Hosni Mubarak’s successor to tremble or wax poetic, but the entire world is asking him to focus on social dignity, opportunity and mobility, and if he can’t deliver these in all of Egypt all at once, then he may as well start where social justice first became law: Sinai.

Amotz Asa-El is the former executive editor of The Jerusalem Post, is a fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, in Jerusalem.