From the Dawn of Printing Why Rare Hebrew Manuscripts Are Commanding Exorbitant Fees

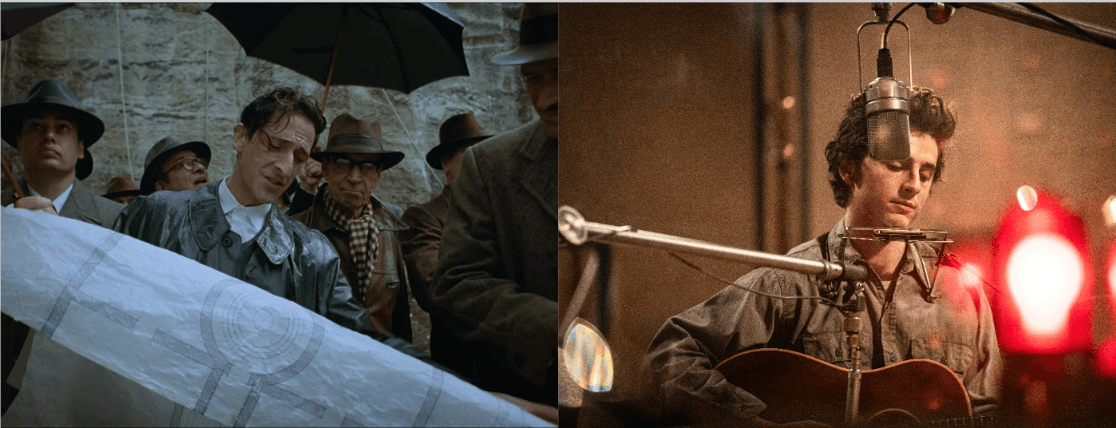

Early in last month’s sale at Kestenbaum & Company, a New York auction house specializing in rare Hebrew books, when a single leaf of Rashi’s commentary on the Pentateuch came on the block, fevered bidding erupted. This first printed edition of the 11th-century French rabbi’s pre-eminent biblical commentary was produced in the small southern Italian town of Reggio di Calabria in 1475, making it the earliest-dated Hebrew-printed book. The fragment far surpassed its $10,000 to $15,000 estimate, ultimately selling to a telephone bidder for $82,600.

Passionate collectors aren’t unique to the Hebraica field, and auctions are notoriously unpredictable, yet the scene still took one’s breath away. Only one of 118 pages was being offered, and it was incomplete at that, the first few lines rubbed off. Even if the estimate was conservative, the price was awesome, considering that the most recent auction of a single page of the Gutenberg Bible, the first book ever printed, went for $55,200.

But for this work by Rashi, there is literally nothing else to be had. The closest thing to a complete copy, lacking the first two leaves, is in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma, Italy, while the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, located in New York, has two leaves from a different copy.

Beyond their extreme rarity, even fragments of Hebrew incunabula — a Latin term referring to the “cradle books” produced in the first 50 years following Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1455 — offer invaluable clues to Jewish life at the time, while illuminating Hebrew bibliography. Complete treasures can command yet higher prices; the top lot at Kestenbaum, a 1492 copy of the Mishnah with commentary by Maimonides from Naples, went for $342,000, more than triple its initial estimate — a record for a Hebrew book on paper.

Not everything on offer was as outstanding, but the sale itself was historic, featuring a private collection of 64 incunables — more than the holdings of most institutional libraries — initially formed by British bibliophile Elkan Nathan Adler and augmented by the Wineman family, now based in Jerusalem, who acquired it after Adler’s death in 1946. The most celebrated Hebraic auctions of the last century, from the Zagayski and Sassoon dispersals at Sotheby’s in the early 1970s to a sale of duplicates from the JTS library at Kestenbaum in 1997, never produced more than a small fraction of the offerings in the recent Kestenbaum sale. The last time anything close to this occurred was in 1913, at a Munich auction of 47 items.

“Whatever I say will sound cliched, but it’s absolutely true. There never has been such a sale before and never will be again.” owner Daniel Kestenbaum said. The sentiment is echoed by Brad Sabin Hill, dean of the library at YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, in New York, who wrote an introduction to the auction catalog: “Usually superlatives are in the realm of exaggeration but as over-the-top as the descriptions might sound, they are all accurate.”

Extraordinarily, 10 days after the Kestenbaum dispersal, which brought a total of $3.78 million, Sotheby’s offered another incunable: one of only two complete copies of the 1493 Brescia Bible (the other is in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan). It sold for $568,000, nearly five times the original estimate.

In a good year, by most accounts, only a handful of Hebrew incunables, if that many, appear on the market. The precise number of existing Hebrew incunables is a matter of dispute, but the most authoritative census, completed by Amsterdam scholar A.K. Offenberg in 1990, documents 139 titles, compared with 40,000 to 50,000 among non-Hebrew incunables. The vast majority of examples are in public and university libraries, and an accounting of all such collections (as well as London’s Valmadonna Trust Library, the world’s largest private collection of Hebrew books and manuscripts — among them incunables — which is open to scholars) totals some 2,000 copies. It’s

virtually impossible to determine how many more are out there, but even when you add the most prominent collections in private hands, at most, Offenberg speculates there are “a few hundred more.”

The paucity of Hebrew incunabula is, of course, a byproduct of Jewish history. We have no way of knowing how many editions were printed initially, but no doubt countless books were destroyed or lost over centuries marred by expulsions, inquisitions, book burnings and censorship, from papal decrees and royal edicts, and later in pogroms and the Holocaust. Talmudic texts were in greatest jeopardy, and material from the Iberian Peninsula fared the worst but, essentially, the fate of the books mirrored that of the people.

“The Christian European world has had monasteries for some 1,500 years, so you have books that haven’t moved for over a millennium,” Hill said. “Jews weren’t rooted in one place long enough for there to be an ancient library.”

There’s also the genizah factor — that texts would be worn by daily use and, per Jewish custom, buried in a depository when they were no longer in good condition. Spanning these two fates, scholars have described a metaphorical genizah, referring to remnants of Hebraica recycled by non-Jews to build up bindings of books or as file folders.

“Often, it was not done out of respect for the text but for financial imperative,” explained Michael Terry, director of the Dorot Jewish Division at The New York Public Library, which has 40 Hebrew incunables in its collection. “Local authorities were reluctant to waste all this good material.”

While the limited survival of Hebraica encapsulates the broad arc of Jewish history, individual books paint vivid snapshots. It’s no coincidence that Hebrew printing began in Italy, despite the fact that this revolution was born in Mainz, Germany, and that Italy was home to 60% of the 40 known Hebrew presses. Presumably, Jews in Germany weren’t allowed to establish their own presses or to enter Christian guilds, while Italy was famously hospitable. “This was a particularly good time — about as good as it got,” Terry said, noting that it was “extremely fashionable to know a little Hebrew in Renaissance Italy.”

From there, Jews transported their craft to Spain and, following the expulsion of 1492, Portugal became a major center for Hebrew printing, until Jews were expelled from there in 1497. In fact, the first book printed in Portugal in any language was Hebrew, the Faro Pentateuch of 1487, the only surviving copy of which is held in London’s British Library. Jews also introduced printing in the Ottoman Empire — and the Islamic world, for that matter — in 1493, with Jacob Ben Asher of Toledo Code of Law, the Arba’ah Turim.

Gershom Soncino, a practicing Jew who was the most prolific Hebrew printer of his time, embodies this narrative. Beginning in 1485, he opened presses throughout northern Italy until 1527, when the changing political climate forced him to move to Salonika, Greece — then part of the Ottoman Empire — and then to Constantinople in 1530. Even within Italy, there is one case of a prayer book that his press began in Soncino in 1485 but completed in Casal Maggiore the following year, suggesting that a license may have been given one minute and withdrawn the next.

Soncino also stands out because half his output was in Latin, Italian and Greek, though he didn’t produce these books until the post-incunable period. There were some typographical and technical influences, cooperation in both directions and the occasional use of Hebrew characters in non-Jewish printing, but more direct involvement of Jews in Christian printing and vice versa before 1500 was limited. There is, however, at least one notable instance of a Jew undertaking non-Hebrew printing: The most famous book printed by Samuel de Ortas, a Jewish native of France who worked in Leiria, Portugal, from 1492 until 1497, was “Almanach Perpetuum,” the Latin version of an astronomical guide by Rabbi Abraham Zacuto, a Spanish Jew whose life virtually overlapped with the incunable period. It is said to have guided Christopher Columbus on his voyage to America.

“Jews were deeply involved in printing as soon as they could, and carried it with them on their travels,” Hill said. It seems that while there might have been some debate as to the halachic permissibility of printing sacred texts, the rabbis quickly embraced the printing revolution. According to Hebrew University Professor Mordechai Glatzer, a leading authority on the history of early Hebrew printing: “We hear a hint that some didn’t agree with it, but after a few years, nobody had any objections. Everyone could see that making these texts more accessible was a very good thing for learning.” (This is in sharp contrast to the Muslim world, which didn’t allow books to be printed until the 18th century, “presumably because of a commitment to handwritten reproduction of the Koran,” according to Hill, who added, “Arabic is among the most beautiful of Oriental scripts” but technically difficult to produce in print.)

Hebrew incunabula also have tremendous material value as artifacts for piecing together bibliography: the history of the books themselves. As primal copies from the infancy of printing, they are, according to Shimon Iakerson — a noted bibliographer at the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies, who recently completed a catalog of JTS’s collection — the link between manuscripts, then the dominant form of recorded information, and the books we know today. Because of variances among manuscripts, printers carefully selected the best copies to work from, in many cases setting the standard text for generations to come. Still, given the painstaking process — each letter was dropped in a frame and printed one by one — errors were inevitable and variances continued, sometimes even between two books from the same edition. “Often, the context or even the meaning of a text was lost,” Kestenbaum said. “The closer you get to the source, the more exact it will be.” Agreed Jack Lunzer, custodian of the Valmadonna Trust Library, “Typographical differences can be absolutely hair raising in importance and have to be gone through with a [fine] tooth comb,” he said. “When you come into the realm of printing history, you need great scholarship to determine what happened when letters fell out during printing.” This gives weight to even small collections. Every single incunable is like a fossil, offering typographical evidence in its paper, watermarks, fonts and formats.

Despite the magic of these earliest Hebrew books and elusive fragments, it would be a mistake to treat all incunables like The Holy Grail. “There are hundreds of post-incunable books that are infinitely rarer,” Lunzer said.

Similarly, Offenberg emphasizes that a sizable number of Hebrew incunables are known in editions of 20 or more, though he does note that one-third have survived in only one, two or three copies. Indeed, it is difficult to discount the inherent rarity of a collecting field that is limited to some 2,500 entities — not to mention the subtle discoveries to be made by historians and bibliographers from even the most elusive fragments, and the sheer pleasure of owning or simply studying a tangible piece of centuries-old Jewish history.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO