Alice’s Adventures: An Iconoclast Shares Her Story

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of “Sexual Behavior in the Human Female,” informally known as the Kinsey Report on Women. For those of us born in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, it’s hard to imagine the shock waves this book created. Back in 1953, sex wasn’t discussed in polite company, and every state had laws against “sodomy” (usually defined as any form of non-procreative sexual activity). Folks were so naive, a survey of college girls found that a high percentage actually thought they could get pregnant by kissing.

Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey blew the subject of sex wide open. Trained as an entomologist whose field of expertise was the taxonomy of gall wasps, he tried to take a nonjudgmental, scientific look at the real behind-closed-doors behavior of 5,940 American women — a sort of taxonomy of sexual activity. And when the results were published, indicating that American women weren’t as “pure” as many people wanted to believe, well, imagine the brouhaha.

A New York congressman tried to get the book banned from the mail. He called the women in it “frustrated, neurotic, outcasts of society” and accused the book of “hurling the insult of the century against our mothers, wives, daughters and sisters.” He said it “contribut[ed] to the depravity of a whole generation, to the loss of faith in human dignity and human decency, to the spread of juvenile delinquency.” Oy vey iz mir. Gasping like a character in a B-movie, one woman wrote to the Scarsdale Enquirer, “Dr. Kinsey has opened a veritable Pandora’s box of incalculable evil such as the world has never known!”

Today, Kinsey’s methodology is considered seriously flawed. (Because of the near impossibility of collecting a random sample, his subjects were volunteers and featured way too many college-age and college-educated white women.) But his work showed the world that sex was a worthy field of inquiry. His numbers may have been skewed, but his findings helped lessen the secrecy, fear and anxiety surrounding sexuality. He taught us that a wide range of behavior was normal. He helped discredit some of Freud’s more sexist theories. His work led to more sex education. And, most importantly, he opened the door to the nonjudgmental study of what women actually do, as opposed to what people thought women should do.

But he didn’t do it alone. Kinsey’s research depended on those women who volunteered to be interviewed. He guarded their identities carefully, marking subjects’ answers in code (“more difficult to break than the secret service codes guarding atomic missile information,” Glamour magazine gushed back in 1953) rather than in words, lest someone someday find the piece of paper. The key to the code was never written down; Kinsey and his three associates memorized it. To ensure the code’s survival, the four never traveled by plane together.

Lately, though, some of Kinsey’s research subjects have outed themselves. I recently chatted with one, Alice Ginott. Kinsey interviewed her in 1943, when she was a 19-year-old sophomore at Indiana University.

“Sixty years later, I still remember being in his presence with such pleasure,” she said. “He made me feel so comfortable. I was a refugee from Europe, and my English wasn’t perfect, but he made me feel so impressed because he actually listened to me and wanted to know how I felt.” Ginott recalls that Kinsey began by asking about family history, infancy and childhood. “Soon, you became very trusting. After an hour, he’d ask if you’d had intercourse. If you had, you’d stay for a second hour. The boys would come and sit outside the door, and if a girl was inside for two hours, that was the girl they became interested in!”

After talking to Ginott for a few minutes about Kinsey, I wanted to know more about her. She emigrated from Czechoslovakia in 1938. “We came home from Yom Kippur services and put on the radio and President [Eduard] Benes said, ‘We made peace in our time, and tomorrow I’m leaving for London.’ Mom said, ‘Kinder, if it’s not safe enough here for Benes, you think it’s safe for us?’”

With relatives in America, her family was lucky enough to get visas. “The day after Thanksgiving is my Thanksgiving,” she said. “That Friday morning was when I first saw the Statue of Liberty. We were on the SS Manhattan, an American ship. We ate turkey onboard — I’d never had it. At home we had goose and duck. And it was my first experience dancing with giants! The American boys on the ship were so tall!”

The family went to Bayonne, N.J., where Alice’s grandparents lived. “The Bayonne paper came to interview me and wrote a story called ‘Alice Comes to Wonderland,’” Ginott said, “‘but the writer made it all up because I didn’t speak English.” Eventually, after learning the language, she got a full scholarship to Indiana University. (Years later, she was so grateful she set up a chair in Yiddish in the college’s Jewish studies department.) After getting a doctorate in psychology at the New School for Social Research in New York, she trained as a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst, then opened a psychotherapy practice — all this in an era when there were very few women members of the American Psychological Association. Along the way, she married and had two children.

Then she met Haim Ginott. “Sholom Aleichem was the shadkhen,” she said, using the Yiddish word for matchmaker. Haim Ginott was the author of the parenting classic “Between Parent and Child,” which sold more than 5 million copies and was translated into 30 languages. (My mother had it when I was little. She recently told me she tried using Ginott’s method of “caring communication”: She said, “I feel upset when I see you hitting your brother,” and I said, “Well, then you better go in the other room.” My mom threw out the book.)

In addition to being a famous child psychologist, Haim Ginott was the parenting expert on “The Today Show.” In 1968, he was in the green room with Marie Waife-Goldberg, who was there to promote her book, “My Father, Sholom Aleichem.” Her husband, B.Z. Goldberg, a writer for the Yiddish Forward, saw how anxious she was and said to Ginott, “You’re a psychologist, do something to make her less nervous.” Ginott paused, then told her in Yiddish, “Don’t be afraid of the goyim!”

Goldberg later sent Ginott a postcard (“You’ve seen how my wife behaves with goyim, now see how she behaves with Jews!”) inviting him to Sholom Aleichem’s annual yahrzeit remembrance, where there were readings and performances of the great writer’s work. Alice was there as well. She’d been invited by her friend Bel Kaufman, the writer of “Up the Down Staircase” and Sholom Aleichem’s granddaughter. “I wore a beautiful light-blue dress I’d bought in Bergdorfs,” Alice said. “It was May, and I was suntanned, and oh, I looked terrific.” The sparks between the two were instantaneous. Seven months later, they were married.

Alice was soon helping Haim with his writing. A man with no children of his own (“I knew it!” my mom chortled), he embraced Alice’s daughters from a previous marriage, happily taking editorial suggestions from the teenaged Mimi. “We said that when we were 80, we would read all of Sholom Aleichem together in Yiddish,” she said. “But man proposes, God disposes. He died of kidney cancer at 51.” They had been together five years.

Alice took over Haim’s syndicated column. She maintained her own practice and watched her daughters and grandchildren grow. Eventually, she married a third time; she has been with her husband Ted Cohn, a business consultant, for 17 years. This year, she ushered a new edition of “Between Parent and Child” (Three Rivers Press) into print. She revised and updated it herself, with H. Wallace Goddard. It’s already in its second printing, finding a new generation of readers. She removed some of the more sexist psychoanalytic statements (“It was the ’60s, it was what we did,” she said with a shrug) and added more anecdotes from her own practice. The book still emphasizes principles of communication, how to praise and criticize children, how to acknowledge their feelings, how to deal with their anger.

Since I’m not one to fail to take advantage of free therapy, I asked Alice how to handle Josie’s recent outbreak of biting. “Josie needs permission to be angry,” Alice said. “You should say, ‘I can see you’re very angry, and when that happens, instead of biting, come and tell me, ‘I am really angry!’” I’ve been trying this. (I’m not sure whether this is related, but lately Josie has been running around quoting the lion in Maurice Sendak’s “Pierre”: “I’d like to eat you, if I may!” But she’s only been pretend-eating me!) I certainly hope Josie responds better to the Ginotts’ advice than I did as a child. But even if she doesn’t, I’m glad I asked Alice.

E-mail Marjorie at [email protected].

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

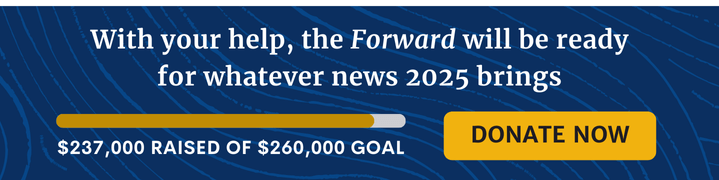

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO