Why Israel’s National Library Is Such A Treasure Trove For The Jewish People

It’s In The Cards: A card catalog at the National Library of Israel Image by Wikimedia Commons

Did you know that Stefan Zweig’s suicide note is housed in the National Library of Israel? So are Gershom Scholem’s love letters to his first wife, which mention the time he saw the poet Chaim Nachman Bialik at lunch, along with the philosopher Ahad Ha’am. In a recent visit, I held my breath as I saw the first Mrs. Scholem’s handwritten responses, half halting Hebrew, half elegant, sprawling German. And I wondered how I had never spent significant time at the library before, even though it is just a 10-minute bus ride from Jerusalem’s central bus station, with minimal traffic.

Israel at 70

The library is housed on the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, not far from the Knesset and the Supreme Court, and all these priceless treasures — and more, like Haggadot from various centuries, and some of the oldest known books written in Hebrew — are accessible to the public. For decades, the National Library was open only to those over 16, and its campus location and overall setup meant it was the province of determined scholars. But the National Library is transforming itself, opening its doors wide, and working on a grand new building, set to open in 2021. Walk a bit past the Supreme Court bus stop and you’ll pass a massive construction site: That will be the new National Library, and bibliophiles the world over are counting the minutes. But I would still say that not enough people know about what’s actually in the library.

I was amazed at how many Israelis — including Israeli literary writers — told me they had never been inside the library; I’m not the only one who didn’t know that Zweig’s suicide note was available for viewing. Or that Scholem’s personal library lives in that library. Or that Martin Buber’s papers are here, along with those of Shai Agnon — Israel’s only Nobel Prize winner in literature — along with those of contemporary giants David Grossman, winner of the Man Booker Prize, and A.B. Yehoshua. Yiddish giants who live on in Jerusalem, in the library, through their archives, include Avrom Sutzkever and Itzik Manger. Plenty of this bounty is online: Every single one of Naomi Shemer’s songs is only a click away.

Part of this nonfamiliarity with the library is a naming issue; the National Library of Israel is simply an incomplete description of what it is: the national library of the Jewish people, as well as the national library of the State of Israel, including all the faiths represented in the country. The other problem the library will always have is that the phrase “Jewish people” — which is, of course, international — is not specific enough, because the building is devoted not only to the Jewish nation, but also to the individual people, dead and alive, who make up the Jewish story.

The entrance hall of the National Library of Israel Image by Wikimedia Commons

That is true not just for what is in the library, ranging from rare books to maps to a 100-square-meter work of art titled “Isaiah’s Vision,” but also for who is in the library. People — both visitors and employees — are the true delights of a visit to the National Library. On my visits to figure out what exactly it held, I checked out the trilingual circulation desk and saw Hasidim, Haredim, secular students and two women in hijabs; there were also career eccentrics, pulpit rabbis and Scholem obsessives, along with two chatty women in the cafeteria who did not hesitate to tell me that they were researching Israeli songs. In the bathroom I encountered tourists. And everywhere, I saw scholars — passionate devotees of the library, many clearly in a state I can describe only as determined bliss.

“It’s a treasure trove of the Jewish people and an oasis for scholars,” Sara Hirschhorn, author of “City on a Hilltop: American Jews and the Israeli Settler Movement,” and university research lecturer at Oxford, told me. “It’s a place where folks of many strokes interact, and that doesn’t happen everywhere in Jerusalem.”

“The lifeblood of the National Library is the collections and the readers who come, like me, every day they are able,” said William Kolbrener, author of “The Last Rabbi: Joseph Soloveitchik and Talmudic Tradition” and a professor at Bar Ilan University. He has been coming to the library for nearly 30 years. “In the other institutions in which I’ve worked and studied in England and America,” Kolbrener said, “the focus of scholarly life is the department office or hallway, the academic version of the watercooler. But in Israel, scholars from all over the country — students, octogenarians, Arabs, Christians, Jews — come to drink bad coffee in the library cafeteria, which is full at 8, an hour before the library itself opens, and meet friends, scholars, from other universities, other departments, to talk about academic research, life, whatever.

“Compared to America, even just New York, Israel has very few public places — no Grand Central Station, no Central Park, no steps to the Metropolitan Museum. The only thing that comes close — and it may not even qualify — is the Western Wall Plaza. In some ways, the National Library is the scholarly Western Wall, a place of genuine diversity — not a place of worship, but of shared curiosity, conversation and friendship.”

There are at least 25 people on the library staff who hold doctorates, including the chief archivist, Stefan Litt, a Berlin native who went to the Hebrew University and has lived in Israel since 1995, and the head of collections, Aviad Stollman, who has his doctorate in Talmud.

Image by Getty Images

The library has always attracted interesting people; it began as one individual’s passion project. In 1890, a Jewish doctor in Bialystok, Yosef Khazanovich, started to charge his patients in books instead of rubles for making house calls. He sent 10,000 books to Jerusalem, and in 1902 Midrash Abarbanel was officially opened — the first free library in Palestine; that was the beginning of what is now the National Library. The Seventh Zionist Congress, held in 1905, decided to build a national library with Midrash Abarbanel as its foundation. So yes, there was a library before there was a state. For years the library was run by its first director, Samuel Hugo Bergmann, a close friend of Kafka’s.

The library’s humanities section has treasures like Sir Isaac Newton’s papers on theology, in digitized form. These days the Library is thinking about 21st-century questions. “What is a library?” asked Stollman, formerly the Judaica curator. “What is a library of the Jewish people?

“In addition to a physical structure, the virtual library holds seemingly limitless potential The audience has changed dramatically as well, as we now aim to reach diverse users of all ages and backgrounds in Israel and around the globe, as opposed to just scholars and rabbis.”

When it comes to acquisitions, the library is always thinking in future tense. “When we collect, we try not to pay attention to contemporary social and political trends or even immediate academic needs,” Stollman said. “We try and think about all potential users, including those in future generations, to the same extent as our current users.”

The library is also clearly trying hard to make itself a place of living culture. There are two programs for Israeli writers; one offers four emerging Hebrew novelists a residency at the library, and the other, Bustan, is a residency program for seven poets who write in Hebrew or Arabic. The most recent class featured five Hebrew-language poets and two Arabic-language poets.

Gershom Scholem Image by WIkimedia Commons

There are also events that are open to the public, such as a recent one on how to become a Wikipedia editor. And there is an ongoing effort to digitize material and to reach out in several languages — Hebrew, of course, but also Arabic and English. The library maintains an active Facebook page in Arabic, and there is a continuing and vigorous effort to bring the building’s treasures and knowledge to communities around the world.

At the end of my visit I was given a black library tote bag festooned with a quotation from Buber’s “Advice to Frequenters of Libraries,” preserved — where else? — in the Buber Archive at the National Library of Israel. One side of the bag is in Hebrew, the other is in English, and in the weeks since my visit I have become more and more charmed by Buber’s suggestion to library travelers, and more and more convinced that he was right:

“After you have visited the library ten times to look at books, go once to look at the readers… see the features, gestures, and postures of each. Thus, you will learn something you will probably not be able to learn as well anywhere else: Books are great, but man is greater.”

Aviya Kushner is The Forward’s language columnist and the author of “The Grammar of God.” Follow her on Twitter @AviyaKushner

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

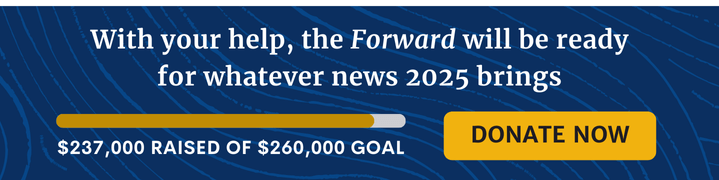

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO