Let’s Do Coffee, Cousin Carrie

Image by getty images

Although writer and actress Carrie Fisher and I have never met, we are related in that four-degrees-of-separation way that many Jews and half-Jews are — that is, my maternal great-aunt was married to her paternal great-uncle. I doubt that Ms. Fisher ever knew Aunt Rebecca and Uncle Jack, who are long deceased, and I only remember meeting them once as a child.

Marla Brown Fogelman

Yet, despite our tenuous familial connection, I have felt a kinship with Ms. Fisher ever since the early 1990s, when I was recovering from my own bout of clinical depression and found a certain type of succor in reading her sardonic, semi-autobiographical novel, “Postcards from the Edge.” I rooted for her protagonist, Suzanne Vale, to find her way out of self-flagellation and self-destruction and into the arms of the nice guy who knew how to calm her anxieties with a sandwich. The acidity of certain lines also made me laugh out loud, including one unforgettable voicemail message: “I am out, deliberately avoiding your call.”

In fact, I loved “Postcards” so much that I wrote a fan letter to Ms. Fisher, mentioning our shared Jewish-Communist Chicago relatives as well as what I viewed as our similarly acerbic writing styles. In the letter, I suggested that we might meet for coffee, since I was coming to Los Angeles anyway, and sent it to an L.A. lawyer friend who knew an entertainment lawyer who knew Ms. Fisher. Though the letter apparently ended up in the entertainment lawyer’s recycling bin, I continued to root for Ms. Fisher to find her way into a good life.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen, as Ms. Fisher’s latest book, “Shockaholic,” makes clear. For every life-affirming action she took — a relationship with Paul Simon, having a daughter, creating a one-woman show to take on the road — an equal and opposite reaction seemed to occur: a final break with Simon, her daughter’s father leaving her for another man and a nosedive back into addiction and depression.

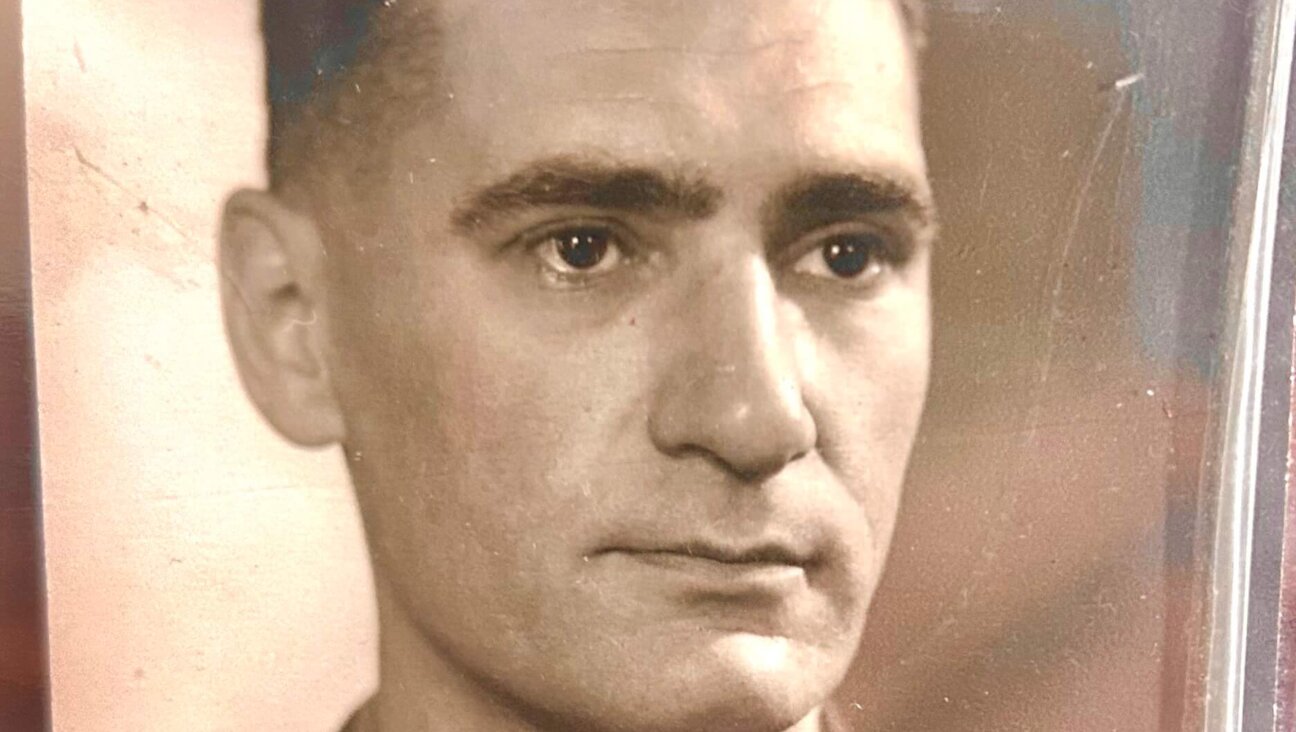

Carrie Fisher Image by getty images

Reading this cleverly insightful, yet emotionally torrential sliver of a memoir, with its focus on electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, and the erasure of memories, I felt sad for Ms. Fisher — and what it has cost her in her role as a daughter of parents (actress Debbie Reynolds and singer Eddie Fisher) who were cast first as America’s sweethearts and then as the subjects of scandal and notoriety. I remember seeing her photo in Look magazine in the 1950s and being sorry for the little girl and her family whom Sonny Boy, as Aunt Rebecca and his family called him, had left for Elizabeth Taylor.

When Ms. Fisher writes how she and Ms. Taylor ultimately became friends, I was struck by her capacity for forgiveness. This capacity is also evident in the “Oy! My Pa-Pa” chapter on her father, with whom she labored to reconcile at the end of his life. Not every daughter of a narcissistic drug addict would have the compassion or reserves to take care of the sick, crazy old father with whom she once did cocaine — as she writes, “Isn’t that what all fathers and daughters do?” But this act of serving as a “good mother” to a bad father seems to have brought her, if not peace, at least a small measure of closure.

To me, this reconciliation was the strength and probably the most important part of the book, and not the description of her strange friendship with Michael Jackson or her account of standing up to a verbal assault by a drunken, sexually harassing Ted Kennedy.

Although I applaud Ms. Fisher’s sharp writing and openness about her psychiatric illness and treatments, I found “Shockaholic” to be ultimately a poignant and painful book, with a real-life protagonist I don’t and really can’t relate to, although she nails the weight problems of women of our certain age. Most distressing of all was learning of Ms. Fisher’s abdication of her role as a parent, albeit temporarily, because of her drug addiction.

In the end, I realize that we don’t have much in common — I was never invited to bring my kids to Neverland, for instance (and thank God). I also did not grow up as the child of performers in celebrity-addled Hollywood, but less glamorously, in Wilmington, Del., as the child of parents who performed Israeli folk music in synagogue halls and at Jewish community events.

I am glad the ECT is working for Ms. Fisher, though. Writing about how her brain had felt stuck in cement before embarking on this treatment, she says, “The ECT blasted my Hoover Dam head wide open, moving the immoveable.”

I am also pleased that her edgy wit seems un-blunted by the shock to her brain waves, as in her description of ECT as “sort of like having your nails done, if your nails were in your cerebral cortex.”

Ms. Fisher chooses to begin “Shockaholic” with a quote by slain Jewish poet and paratrooper Hannah Senesh, on “people whose brilliance continues to light the world though they are no longer among the living. These lights are particularly bright when the night is dark.”

Despite its pathos, the fact that she selected this passage somehow gives me a sense of hope for her future.

So yes, even if we never have coffee, I am still rooting for “Cousin Carrie” to have a good life.

Marla Brown Fogelman is a freelance writer living in Maryland. She is working on a book about her experience interviewing American Jewish veterans of World War II.