Interfaith Insults

Image by getty images

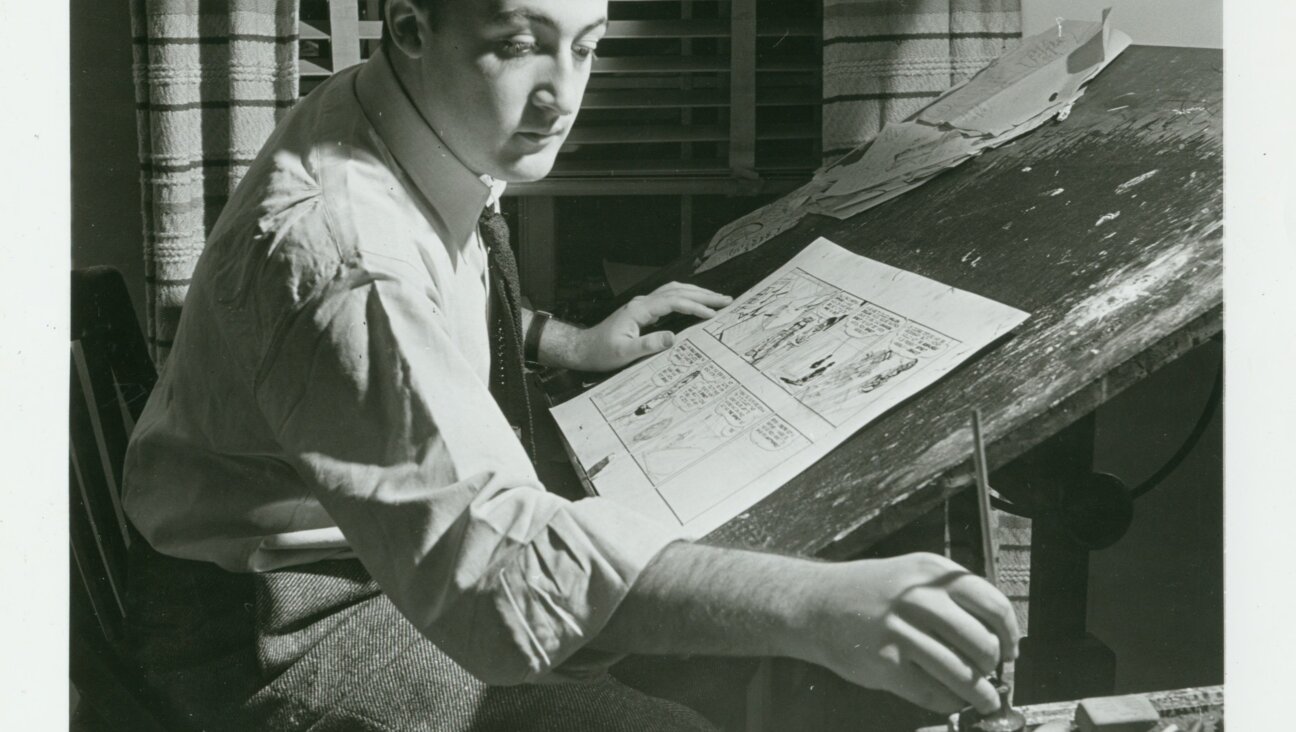

Uneasy Peace: Since Jews and Christians have not always gotten along, it is hardly surprising that Yiddish is full of perjoratives for Christians. Image by getty images

From Jacob Mendlovic of Toronto comes a letter of complaint about “the intense hostility of Haredim,” or ultra-Orthodox Jews, toward gentiles as manifested in such “Jewish n-words” as sheygets (a non-Jewish boy; from Hebrew shaketz, “abomination”); shikse (a non-Jewish girl); orel (an uncircumcised man) and akum (heathen — a talmudic acronym for ovdey kokhavim u’mazalot, “worshipers of stars and signs”). And that’s not all. “When a Haredi Jew dies,” Mr. Mendlovic writes, “Haredim use the Hebrew-derived expression er iz nifter geven, ‘He passed away,’ whereas when a gentile dies, they say er iz geshtorbn [the past tense of German-derived shtarbn, to die] — or worse yet, using the Hebrew word peger, an animal carcass, er hot gepeygert. In their literature and newspapers, they make a sharp, punning distinction between a beys-tfile, a ‘house of prayer’ or synagogue, and a beys-tifle, a ‘house of folly’ or church. If you want, I can mail you examples of all this.”

There’s no need to. The hostility of some Jews, particularly insular ones, toward gentiles is hardly news, and certain Yiddish turns of phrase that express this, like er iz gepeygert, “He [a gentile] croaked,” are truly ugly. But although there’s no real excuse for such turns of phrase, one needs to remind oneself of two things. The first thing is that Yiddish was, until recently, an Eastern European language, and that in Eastern Europe, where millions of Jews were murdered by Christians not very long ago, neither Jews nor Christians made a secret of not liking each other. (This is, of course, a generalization. There were always many exceptions to the rule.) The second thing is that Yiddish has a whole set of binary terms for Jews and gentiles that, while they certainly reflect a Jewish sense of superiority, do not necessarily reflect animus. Rather, they come from a traditional Jewish sense that Jews and gentiles inhabit separate universes, one sacred and the other profane, and that language may sometimes indicate this.

In most cases, Yiddish made such distinctions in matters of religious practice. Although Yiddish-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe did not call a church a beys-tifle unless they wished to be derogatory (the neutral terms kirkh and kloyster were far more common), and beys-tfile was not a frequent term for a synagogue, once in a church or synagogue, the words used for Jewish and Christian worship were not the same. When a Jew prayed, he “davened” (the word is of obscure origins, though many years ago, in these pages, I tried to trace it back to Hebrew); for Christians, the verb was molyen zikh, from Polish modlić się. The holiday the Jew prayed on was a yontif (from Hebrew yom tov, “good day”); the Christian celebrated a khoge (from Aramaic ḥ aga, “holiday”). A sermon in the church was a preydik (from German predigen, to preach); a sermon in the synagogue was a droshe (from Hebrew d’rashá). The lectern the Christian preacher stood at was a shtender; a shtender in a synagogue was a stand for a book, while a preacher’s lectern, also used by the prayer leader and the Torah reader, was the amud (from Hebrew again).

The emphasis was on difference, not derogation. It was often reinforced, as can be seen, by the use of a Hebrew word with sacral associations for Jews and the use of a non-Hebrew word for gentiles. The Jewish slaughter of kosher animals was designated by the verb shekhtn, from Hebrew shaḥ at; Christian slaughter was koylen, from Russian kolot. A Jewish cemetery was Hebrew beys-oylem, a “house of eternity”; a Christian cemetery was a tsvinter, from Ukrainian tsvintar. (This word ultimately goes back to Greek koimeterion and Latin coemeterium, and has such Eastern European cognates as Polish cmentarz and Hungarian tzinterem.) Burying a gentile was bagrobn, a Germanic word related to English “grave”; burying a Jew was more often mekaber zayn or brengen tsu kvure, from Hebrew kavar, “bury,” and k’vurá, “burial.”

One could go on. A saintly Jew was a tzaddik, from the Hebrew word for “righteous man”; a saintly Christian was a heyliker, from German heilig, “holy.” A scholarly Jew was a lamden, from Hebrew lamad, “learn, study”; a scholarly Christian, a gelernter. And once again: heyliker and gelernter were respectful terms. They just referred to a different realm, a separate sphere of existence.

None of this is to argue for or against Mr. Mendlovic’s assessment of ultra-Orthodox attitudes toward gentiles. Having little first-hand familiarity with the Haredi world, I have no idea how much we are talking about unthinkingly inherited linguistic usages and how much about genuine prejudice. Although words like “goy,” sheygets, shikse, orel, etc., can certainly be contemptuous, they don’t have to be. They can simply express a sense of otherness, of the enormous gulf dividing Jews from gentiles that was the common experience of many Eastern European Jews and continues to be that of ultra-Orthodox Jews today. Feeling superior as a Jew doesn’t necessarily mean denying a non-Jew’s worth, even if you think you’re lucky not to have been born one.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]