Fierce Reaction Greets Study of Alleged Hate in Palestinian Textbooks

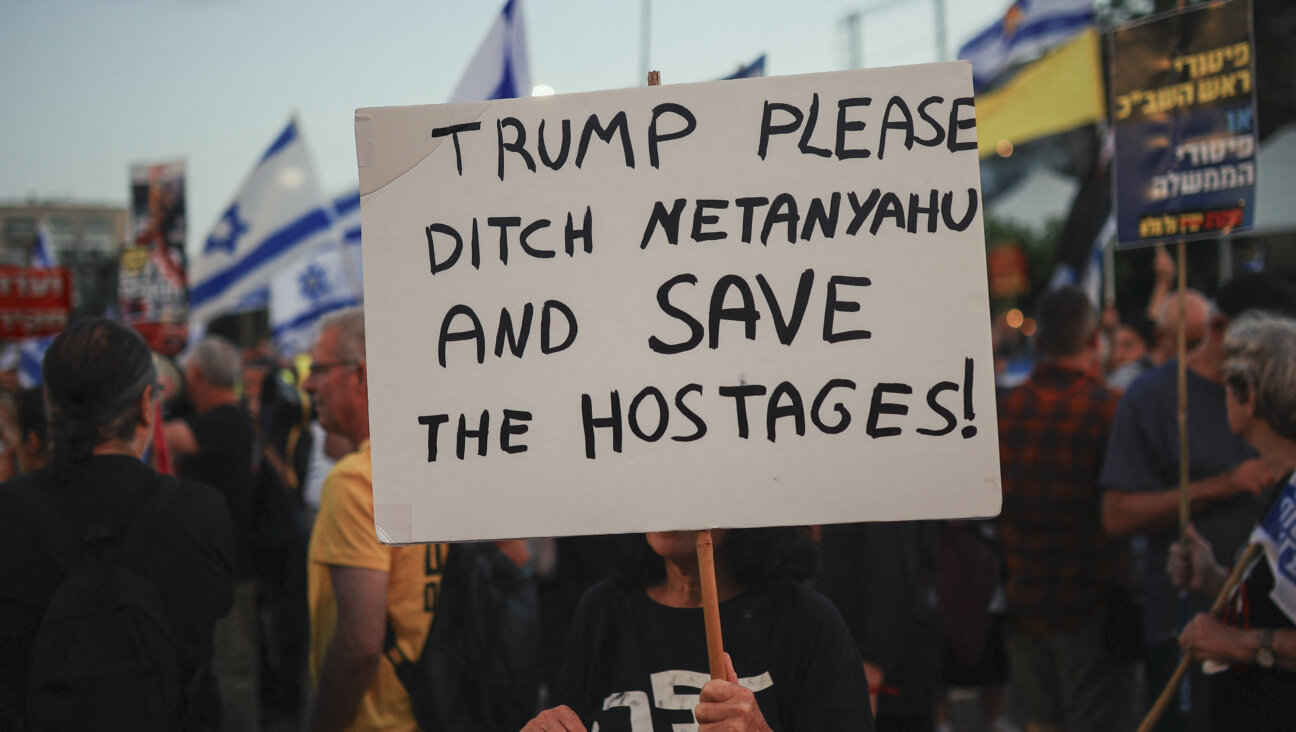

Textbook Case of Controversy: A new study was supposed to settle the question of whether Palestinian textbooks spur hatred toward Jews and Israel. Instead, the study itself has became a focus of controversy. Image by getty images

A controversial in-depth study that clears Palestinian Authority school textbooks of the charge that they demonize Jews and Israelis has become an orphan, virtually upon its release.

Since Yale University psychiatry professor Bruce Wexler, Bethlehem University professor Sami Adwan and Daniel Bar-Tal of Tel Aviv University rolled out their study’s results February 4, the Council of Religious Institutions of the Holy Land, which commissioned the project, has disavowed the study.

Israel’s Chief Rabbinate — one of the council’s four constituent members — has, too. The U.S. State Department, which fully funded the study, has refused to comment on it. And the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, which sent out a press release February 5 announcing that it would host a Washington rollout for the study, has now called that release’s distribution an accident.

According to Wexler, the fury over the report is a recent development. Last May, he said, the study received unanimous support from its 17-member scientific advisory panel, an international group of education experts, who drafted and signed a document approving both the methodology and the findings. But now, three members of the panel have publicly denounced the project.

Those involved in the project attribute much of the response to it to Israeli government officials, who have led the charge against the report, denouncing it as “misleading,” “highly distorted” and ”biased, unprofessional and significantly lacking in objectivity.”

The study, which looked at textbooks used by both Israelis and Palestinians, found that, with some exceptions on both sides, neither side’s books dehumanize the other as a group. But the study also found that books used in schools on both sides distort history and use facts selectively to favor their own respective narratives, at a significant cost to building peace.

The Palestinians’ alleged demonization of Jews and Israel in school textbooks has been a long-standing grievance for pro-Israel advocates. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the Palestinians have voiced satisfaction with the study’s findings. But on the Israeli and Jewish side, protests reached a fever pitch.

One adviser to the study warned Wexler, who is Jewish, that he was in danger of becoming “another Goldstone,” a reference to Richard Goldstone, the South African Jewish jurist who became a pariah among many fellow Jews for chairing a United Nations report that criticized Israeli military actions in Gaza.

Wexler stands by his group’s findings. “The goal was to provide the information so discussion can be informed by facts,” he said. “We have done that, and that is why I am shocked by the vehement response to discredit us.”

The study, which has been four years in the making, began in 2009, when the Council of Religious Institutions of the Holy Land — a consortium of the senior leaders of Islam, Judaism and Christianity based in Jerusalem — commissioned Wexler, who is American, and his Israeli and Palestinian colleagues to design and conduct the research project with a $590,000 State Department grant.

Following years of regular but fragmentary attacks by Israel and its supporters — including testimony before Congress — on alleged hate passages that they claim permeate Palestinian textbooks, this study was designed to be nothing if not comprehensive. And unusually, it was designed to examine the textbooks of both sides, not just the Palestinians.

The researchers examined 94 books from Palestinian school systems in Gaza and the West Bank, and 74 books from the Israeli state secular and state religious school systems, analyzing 1,000 categories of information, such as narrative passages, poems and photos.

While the relative absence of “extreme negative characterization” of the other by both sides rose to the top of the researchers’ findings, the study found that both Israeli and Palestinian textbooks portrayed the other as the enemy, and each collection of textbooks presented their own respective group in almost exclusively positive terms.

The study also found a deep lack of information about the other in each side’s books. The negative depictions and omissions of the other are most pronounced in books used in Israel’s Orthodox religious schools and in Palestinian books. Israeli secular books were found to be the most self-critical of the three categories.

Perhaps nothing distills more starkly just how this dynamic of mutual effacement works than the researchers’ findings regarding each side’s textbook maps.

According to the study, 58% of the post-1967 maps in the Palestinian schoolbooks show the polity “Palestine,” with its area incorporating everything between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, including present-day Israel. There is no mention of Israel.

The Israeli books examined came off even worse. Seventy-six percent of the post-1967 maps in them show Israel as the area between the river and the sea, with no mention of the P.A. and no notation of the so-called Green Line that separates Israel from the West Bank and Gaza — the territories Israel conquered in the 1967 Six Day War and that it continues to occupy, but has never annexed.

“This type of education can create a lasting obstacle to peace,” Wexler said. “If you grow up seeing maps that seem to imply that the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea is your homeland… and you are asked to give up some of that land to make two states, you would feel you are losing something that you never had to begin with.”

Many of the critics’ substantive arguments against the study have to do with the way that Wexler and his team categorized their findings. The study stressed the fact that Palestinian and Israeli schoolbooks contain very few “extreme negative characterizations” that dehumanize or demonize the other.

One rare instance, in an Israeli book used in the state religious sector, refers in toto to the residents of a decimated Arab village — now the site of an Israeli settlement — as a “nest of murderers.” Another such example, from a Palestinian book, describes an Israeli interrogation room as a “slaughterhouse.”

But critics say that the narrative threaded throughout the P.A.’s books describes the Zionist movement and Israel’s founding as a central source of Palestinian problems — and argue that this itself is a form of dehumanization.

Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, wrote in a column on The Huffington Post’s website that what he found particularly problematic was the study’s “unwillingness to accept that when Palestinian texts reject or ignore Israel’s existence, that [this] is not dehumanization.”

Asked about the researchers’ finding that Israeli textbooks do the same, ADL’s deputy national director, Ken Jacobson, said that comparing the two was “an asymmetry.”

“The whole question of the Palestinian state is of much more recent vintage,” he said. “Israel does need to improve its teaching about the Palestinians. But the point is that on the Palestinian side [acceptance of Israel] is the core issue of the conflict for Israel. They are muddling two kinds of issues by bundling it all together.”

Wexler, meanwhile, rejected the notion that mutual effacement by either side of the other — as harmful as that might be — constitutes demonization. That, he said, occurs when one side uses a broad brush to negatively depict “the character of a people,” and not just “some bad action” by its government or citizens.

Dehumanization, Wexler said, “is very different from leaving [the enemy] off a map.”

Elihu Richter, executive director of the Genocide Prevention Program of the Hebrew University-Hadassah School of Public Health and Community Medicine, and one of the three dissenting members of the project’s advisory committee, thinks otherwise. “I warned [Wexler] all along, ‘You don’t want to become another Goldstone,’” Richter said.

Two other members of the scientific advisory panel have also come out against the report. Arnon Groiss, an independent researcher with expertise in Arabic, said that he found several passages in the Palestinian textbooks that were “explicit enough to show belligerent positions,” that should have been cited in the study. But the academics leading the report, he said, rebuffed him.

Asked about this, Wexler said that he carefully responded to Groiss’s queries, and that even if every one of his examples were added to the study, the statistical findings would have been the same.

Bar Ilan University Talmud professor Daniel Sperber, the third dissenting advisory panel member, offered a criticism more political than substantive: The release of the study during a time when Israeli-Palestinian relations are strained and when Israel is in-between governments was counterproductive.

“These are tense times in the Middle East, and the idea [of the study] was not to increase tensions,” he said.

The harshest criticism, however, has come from the Israeli government. In a press release issued before the study went public, the Ministry of Education attacked the very concept of examining both sides’ textbooks in tandem. “The attempt to create a parallel between the Israeli education system and the Palestinian education system is completely unfounded and lacks any basis in reality,” the document read.

The statement said that the study’s findings legitimated the government’s decision not to participate in the research.

According to both Wexler and a source connected to the Council of Religious Institutions of the Holy Land, it was the Israeli government’s fierce response that forced the Chief Rabbinate, a member of the council, to walk away from the study. The Council source claimed that Yossi Kuperwasser, director general of the Israeli Ministry of Strategic Affairs, “went ballistic” when he heard the findings of the study and pressured the rabbinate to “pull back.”

The source further claimed that Kuperwasser pushed the rabbinate to “character assassinate” the authors of the study in a statement, but that the rabbinate did not agree to this.

Asked about this, Kupperwasser told the Forward that he did speak to the rabbinate about what its response would be but did not “in any way pressure them.” He called the allegation of such pressure “baseless.”

The Rev. Trond Bakkevig, convener of the council, said the council had withdrawn its support because the researchers “widened the remit [of the study] beyond our competence and what we asked for.” But Wexler contested this adamantly.

“The original assignment given to me by the council was to look at how the other is portrayed, including, but not limited to religion,” he said. “That was in the grant from the State Department from the start.”

Professor Nathan Brown of George Washington University, another member of the advisory panel who has himself extensively studied Palestinian textbooks, said that he backs the project’s findings: “I don’t think that this study would surprise any scholar who has actually read the books,” he said.

Nevertheless, Brown questions whether the study should have ever been launched — albeit for reasons much different than those of Israeli government officials. The “logic of the report,” he said, assumes that textbooks generate political attitudes in its readers.

“It often goes the other way around,” he said. “Political cause creates textbooks.”

Like Sperber, he suggested that the timing of the study’s release — and indeed, the study itself — might have been off, but again, for somewhat different reasons.

In the midst of bitter conflicts, Brown observed, battling factions are unlikely to back away from their depictions of the enemy. Asking Israelis and Palestinians to revise their views on the other, while they remain locked in conflict, would be akin to pushing for schoolbook reform in the United States or China during the Cold War.

“This is not a post-conflict situation,” Brown said. “To come up with post-conflict techniques in a conflict still being fought is, to me, premature.”

Contact Naomi Zeveloff at [email protected]

Contact Nathan Jeffay at [email protected]