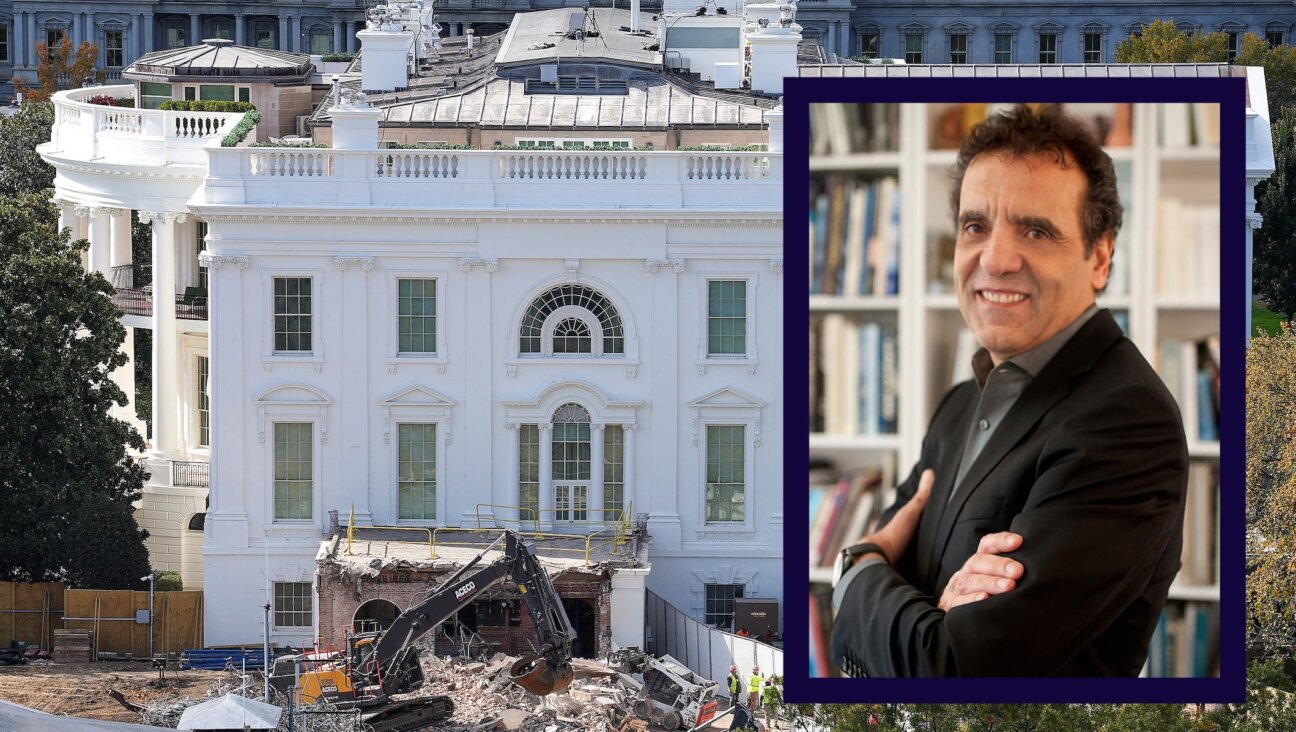

26 Billion Bucks: The Jewish Charity Industry Uncovered

Image by Kurt Hoffman

The American Jewish community’s network of charity organizations is a font of Jewish power, a source of communal pride and a huge mystery.

We know that the network exists. We know that its federations, social service groups and advocacy organizations influence America’s domestic and foreign policy, care for the old, educate the young and send more than a billion dollars a year to Israel.

Yet until now we’ve had no idea what the network looks like.

Individual organizations file tax returns. Some umbrella groups offer information on their members’ work. But no one has measured the network as a whole: how much it spends, how much it raises, how it prioritizes causes, how much it gets from the government.

Now, the Forward has identified and reviewed tax documents filed by more than 3,600 Jewish organizations in the most comprehensive survey ever of the financial workings of this Jewish tax-exempt ecosystem. And the results are striking.

The Forward’s investigation has uncovered a tax-exempt Jewish communal apparatus that operates on the scale of a Fortune 500 company and focuses the largest share of its donor dollars on Israel.

This analysis doesn’t include synagogues and other groups that avoid revealing their financial information by claiming a religious exemption. But even without this substantial sector, the Jewish community’s federations, schools, health care and social service organizations, Israel aid groups, cultural and communal organizations, and advocacy groups report net assets of $26 billion.

Israel: Contributions to the functional agencies of the Jewish charitable network, broken down by category. Israel-related groups get the most.

That’s more than the Las Vegas Sands Corp., which owns casinos all over the world. It’s about the same as the CBS Corp. which owns 29 TV stations, 126 radio stations, the CBS Television Network and Simon & Schuster. The Jewish communal network of tax-exempt groups employs as many people as the Ford Motor Co.

And its $12 billion to $14 billion in annual revenue is more than the federal government’s 2014 appropriation to the U.S. Department of the Interior, which manages a fifth of all the land in the United States, runs the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the national parks, and administers Guam, American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

“What exists out there is a lot of guessing,” said Eric Fleisch, a postdoctoral fellow at Brandeis University who recently completed a thesis on American Jewish giving to Israel. “Not very much has been written about this at all.”

In the coming weeks, the Forward will publish a series of articles reporting the results of its investigation. The Forward can now describe a Jewish apparatus that, despite extensive rhetoric about the importance of Jewish education, still dedicates the largest share of its donor dollars to Israel-related causes. It’s an apparatus that benefits massively from the U.S. federal government and many state and local governments, in the form of hundreds of millions of dollars in government grants, billions in tax-deductible donations and billions more in program fees paid for with government funds. And it’s an apparatus that requires vast resources to support itself, spending $2.3 billion a year on management and fundraising — and $93 million on galas alone.

The Forward’s database is based on files the IRS made available in 2013 that consist of figures from all the Form 990s and Form 990-EZs — the forms the IRS requires of all nonreligious charities — that were submitted in the 2012 calendar year. The findings in these stories reflect mostly tax periods ending in the 2011 calendar year. A more detailed explanation of the Forward’s methodology in constructing its database is included in an accompanying story.

The Contours

The Jewish not-for-profit network is shaped like a daisy.

The white petals are the functional agencies, offering concrete services like education and counseling, or public advocacy on various issues. They run the nursing homes and food banks, and advocate in Washington. At the yellow center are the communal grant makers, organizations like the Jewish federations and the large communally sponsored donor-advised funds that exist largely to finance the functional agencies.

All told, the whole daisy reports $14.6 billion in revenue in a year. Given the likelihood that a large proportion of the $2 billion that these groups report giving out in grants to organizations goes to other Jewish tax-exempt groups and is thereby counted twice, the actual revenue is probably between $12 billion and $14 billion.

This daisy structure has existed for well over a century in the United States. The Boston Jewish community founded the first federation in the country in 1895; similar groups soon followed in other cities. In 1902, the American Jewish Year Book counted thousands of Jewish organizations across the United States, including schools, clubs and fraternal lodges.

Since then, the network has grown enormously larger and more complex. “In many ways, we had a better sense of Jewish giving back then than we do today,” said Jonathan Sarna, a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University.

Jewish charity experts have warned in recent years that the old daisy structure is disintegrating — that major givers are abandoning the federation system in favor of giving directly to the functional organizations. Yet the Forward’s investigation shows that the communal grant-making groups in the center of the daisy still play a dominant financial role in the Jewish not-for-profit network.

Taken together, these communal grant makers have $11.6 billion in net assets, 43% of the network’s total. They also control a huge portion of the flow of donated cash.

They make $1.7 billion in grants to charities in the United States each year, while the functional agencies take in $3.6 billion in contributions. It’s fair to assume that the vast majority of the $1.7 billion is granted to other Jewish groups, and therefore that roughly half of the $3.6 billion raised by the functional agencies comes through the communal fundraisers.

Cash for Israel

The largest share of donor dollars ends up with organizations that focus on Israel.

Of the $3.7 billion in donations that the functional agencies of the communal apparatus receive in a year, 38% goes to Israel-focused groups. That’s more than any other category, including education, which gets just 20% of donations.

Education groups’ cut drops to 16% if Brandeis and Yeshiva universities are excluded from the count. The remaining groups, mostly Hillels, day schools and summer camps that focus primarily on Jewish, rather than secular, education, receive $617 million in donations per year — $807 million less than Israel-focused groups.

“It is quite striking that donor contributions to Jewish education… appear to be quite small, relative to other sectors,” said Theodore Sasson, senior research scientist at the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies and the Steinhardt Social Research Institute, at Brandeis.

The high proportion going to Israel-related groups, Sasson said, is “further evidence… that American Jews are deeply interested in Israel even as they take a variety of different positions with regard to contentious political issues.”

The 619 Israel-focused organizations include advocacy agencies, like the American Israel Public Affairs Committee; groups that send money to Israel, like American Friends of The Hebrew University, and hybrids, like Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America.

American Jews give other money to Jewish institutions that isn’t reflected in this breakdown: dues and donations to synagogues, tuition fees to Jewish day schools. But the $3.7 billion represents the philanthropic discretionary spending of American Jews, the money that they choose to give after their obligations to synagogues and other fees are met.

Health care and social service groups receive 20% of this pot, while culture and community groups get 12% and education groups get 20%.

The tilt toward Israel-related causes is also reflected in the grants that the network makes overseas.

All told, Jewish groups make $1.9 billion a year in grants overseas. Charities no longer need to report the specific destination of their overseas grants, so it’s impossible to say what proportion of these dollars went to Israel. Still, half the overseas grants come from Israel-focused organizations, and it’s fair to assume that a significant proportion of the money granted overseas by communal fundraising groups goes to Israel, as well.

Those overseas grants make up 15% of the total program expenses of the network. The Jewish communal fundraising groups, meanwhile, report spending 25% of their total program expenses on overseas grants.

Money in New York

The financial center of the Jewish communal network is located firmly and disproportionately in New York. New York State is home to just a quarter of America’s Jewish population, but $7.2 billion of the $14.6 billion in annual revenues reported by the network go to organizations based there.

The second-largest state by revenue is California, with just $1.2 billion a year, while Massachusetts comes in third, with $930 million. The network is totally absent from Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and North Dakota.

Groups located in Chicago have net assets of $1.6 billion, more than any city but New York City. San Francisco comes in third, with $1.1 billion, followed by Waltham, Mass., where Brandeis University is located.

Most of the largest organizations in the network by any measure are located in New York City.

Yeshiva University spends the most in a year of any Jewish group, followed by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, which distributes funds from the German government to Jewish individuals and charities. Other top spenders include Brandeis, the New York-based American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and Beth Abraham Health Services, a Bronx-based health care organization that is a network agency of UJA-Federation of New York.

The Rest of the Iceberg

There’s still a lot missing from the sketch of the Jewish not-for-profit network offered by the Forward’s new analysis. If the 3,600 Jewish organizations that filed with the IRS are a snowy iceberg, the Jewish groups that claim a religious exemption and don’t file are the mountain hiding underwater.

The IRS doesn’t require synagogues to file tax returns. Synagogue umbrella groups aren’t required to file either, nor are elementary or high schools that are affiliated with a synagogue. Most rabbinical seminaries qualify as an “integrated auxiliary” of a synagogue or group of synagogues, meaning that they don’t file either.

It’s impossible to say how many such Jewish groups there are, or how much money they raise and spend. In 2010, a University of Washington professor named Paul Burstein published an analysis of a different IRS database that counted 3,495 Jewish religious organizations.

Burstein’s findings suggest that the total number of organizations in the Jewish network may actually be more than twice the number of those that file tax returns. Some of those religious groups may be small congregations with tiny budgets. But others are large: The Jewish Theological Seminary, which is affiliated with the Conservative movement, has a busy campus on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion has three campuses in the United States and one in Israel.

The $12 billion to $14 billion in annual revenue, the Forward’s best estimate based on tax filings, is probably billions of dollars short of the network’s actual size.

Comparisons Difficult

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to compare the Jewish communal network with networks of charities built by other ethnic and religious groups.

In his 2010 paper, Burstein wrote that no one had conducted a comprehensive review of the charities surrounding any American religious or ethnic group. This appears to continue to be the case. Compounding the problem is that other religious and ethnic groups don’t organize their charities in the same way that the Jewish community does.

Mainline Protestant denominations, for example, conduct their charitable work through their denominational organizations, which in turn receive much of their revenue from their member churches. All these entities claim religious exemptions from the IRS’s filing requirements, so their financial data are opaque. Evangelical Protestant denominations do have large networks of affiliated nonreligious charitable groups. But no estimates appear to exist of the size of the network of these so-called para-church organizations.

What we can say is that the Jewish organizations make up a tiny fraction of the total not-for-profit sphere. All told, the groups that filed Form 990s and Form 990-EZs in 2012 reported receiving $365 billion in contributions, gifts, grants and dues after duplicate filings were excluded. Jewish groups reported getting $7.5 billion — roughly 2% of the total.

Which, fittingly, is roughly the Jewish percentage of the U.S. population.

NEXT WEEK: Government subsidizes the Jewish charity network heavily. We examine the network’s reliance on government aid through grants, charitable tax deductions and program fees.

Contact Josh Nathan-Kazis at [email protected] or on Twitter @Joshnathankazis