How Living In A Muslim Country Made Me Lose My Faith In Orthodox Judaism

Image by iStock

A version of this article originally appeared in Plus 61J, an Australian Jewish publication.

I had my greatest revelation about Judaism while studying Arabic in Cairo. I was in the middle of my master’s degree in Middle Eastern Studies at St Antony’s College, Oxford. Part of the course requirement was spending the summer learning a language. So a few classmates and I spent the summer eating ful, falafel and koshari and studying Arabic at the British Council in the Egyptian capital.

It was my first time in the Middle East outside of Israel and the scale of this bustling city of millions was different to anything I had ever experienced. There were people everywhere, including communities living in the cemeteries.

I made an effort to attend synagogue in both Cairo and Alexandria. It was sad to see what had once been flourishing communities reduced to shells of their former selves. There were no rabbis, no one who could lead services and no Hebrew-Arabic siddurim, which meant services had more of a social than religious emphasis.

Walking back from synagogue one afternoon I realised that there were many religious Muslim women who, according to their tradition, were modestly dressed. As this was the 1990s, that included wearing trousers and sometimes a loosely-tied head scarf over their hair. According to their religious leaders (all male), this was acceptable and the women were devout practitioners of Islam.

Our Jewish religious leaders (all male) had meanwhile come to a different interpretation of what modesty, or tzniut, entailed. There is a Biblical injunction that women cannot wear men’s clothing, so many Orthodox women do not wear trousers or shorts even if they are loose fitting and designed for women.

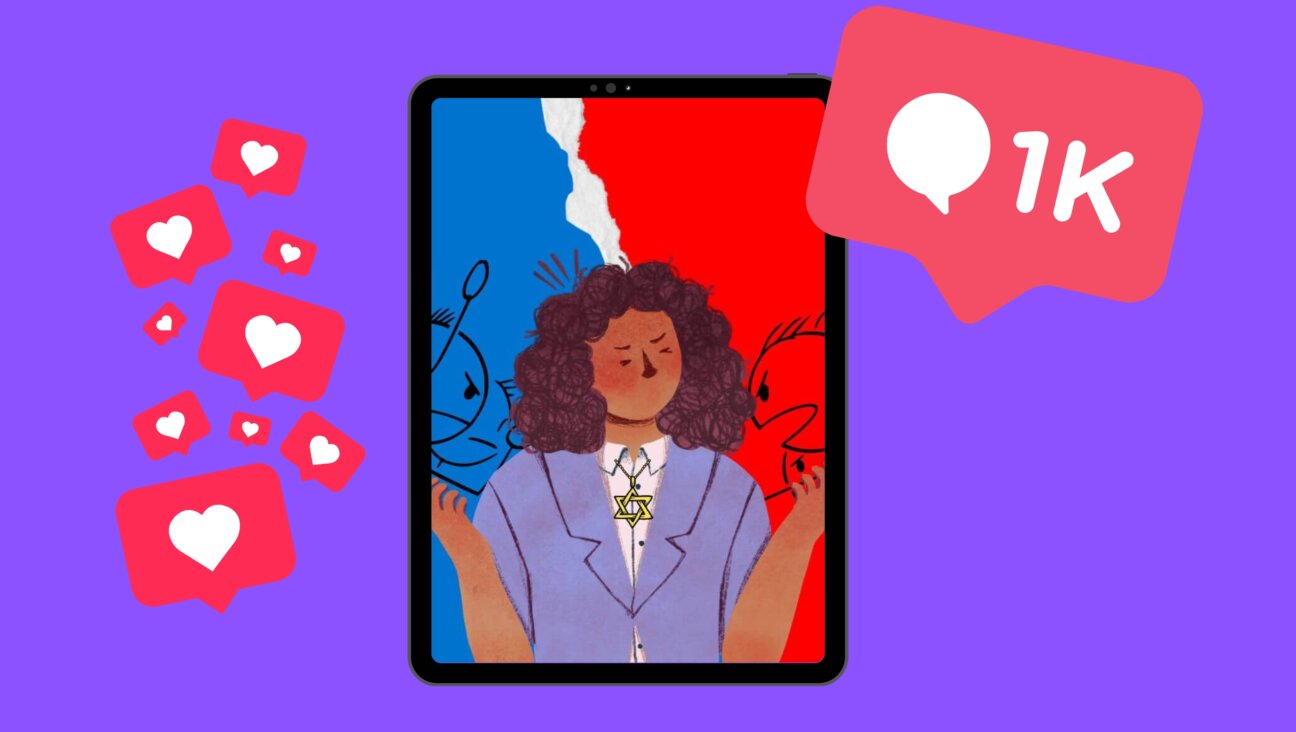

Seeing these “frum” Muslim women wearing trousers made me feel that the religious norms we accept are rather arbitrary and often interpreted through the lenses of men, if not man-made. This has been reinforced over the years as the male interpretation of modesty has become more extreme in both Islam and Judaism.

Today women in Cairo routinely wear a hijab or niqab with pants, while young Orthodox girls in some neighborhoods of Israel face verbal and physical abuse for wearing sleeves that stop above the elbows.

I don’t mean to diminish the enormous wisdom and knowledge of our Jewish sages, but I find it hard to accept that all this wisdom, including how women should dress and act, was all interpreted, stored and passed down to men, giving women no say in matters which directly affect them. Talk about disempowering.

These feelings were recently reinforced while watching a video from Israeli TV in which Orthodox Rabbi Dov Halbertal, former head of the Office of the Chief Rabbi, publicly defended a Haredi magazine’s decision to blur the image of women in the Holocaust.

Rabbi Halbertal claimed it was done to “protect” the women and their image. I was angered at the idea that a man, no matter how learned, could be making such a presumptuous opinion about me and all of my gender, particularly those who had suffered so deeply in the Holocaust and whose identity was now being erased — in their “honor.”

This sentiment is not new for Rabbi Halbertal, who previously said “there is no greater value for Haredi women than modesty,” in justifying opposition to a campaign to raise awareness for breast cancer screening in the Haredi city of Bnei Brak. So without discussing the idea that saving a life should trump the needs of modesty, I think it’s important to recognise the increasingly damaging effects of such attitudes, which are not isolated to one or two rabbis.

Targeted advertising campaigns to the Haredi community in Israel have been the norm for many years, with advertisers attempting to show respect for community norms. However, as increased stringencies become more commonplace, women have literally been erased.

Last year, Ikea in Israel printed an entire catalogue with no women in it, in deference to Haredi norms. If that wasn’t bad enough, government-funded institutions like health funds routinely show only male images in Haredi areas, effectively rendering 50 per cent of the population invisible, even though the women pay taxes and are users of these health funds.

In Israel this campaign is not just about printed images but also extends to women dancing and singing in public, with Haredim refusing to attend ceremonies where these events occur. As the Haredim continue to grow demographically and politically, these exceptions become the new norm.

The separation and marginalization of women manifests itself in increasingly extreme outcomes. Haredi soldiers refuse to stay on a base with women, there are separate sidewalks for men and women in Haredi areas and the list grows. This effort to remove women from the public image has huge ramifications for our daughters and ourselves, actively diminishing our role models and possibilities.

By controlling and marginalizing women, organised religion continues to play a role that today seems antiquated to me. For this reason I have found a new home in the Masorti community where prayer and opportunities are open to all and not divided on gender lines. And nobody cares what I wear.

Yet after moving back to Sydney — and 11 years later — I am surprised how often I continue to feel marginalised at community events. More often than not an entire evening will have all male speakers, or at best a token female moderator. Organizers either don’t notice or don’t care that 50 percent of the audience has no public representation. It makes me feel invisible, irrelevant and angry.

While this is nothing on the scale of what is happening in Israel, it’s hugely detrimental to both the men and women in the audience and the community in general.