Why Can’t You Let Us Be ‘Just Jewish’?

George Mason Elementary School Student Activist Naomi Wadler speaks onstage at the 2018 Women In The World Summit at Lincoln Center on April 14, 2018 in New York City. Image by Getty Images

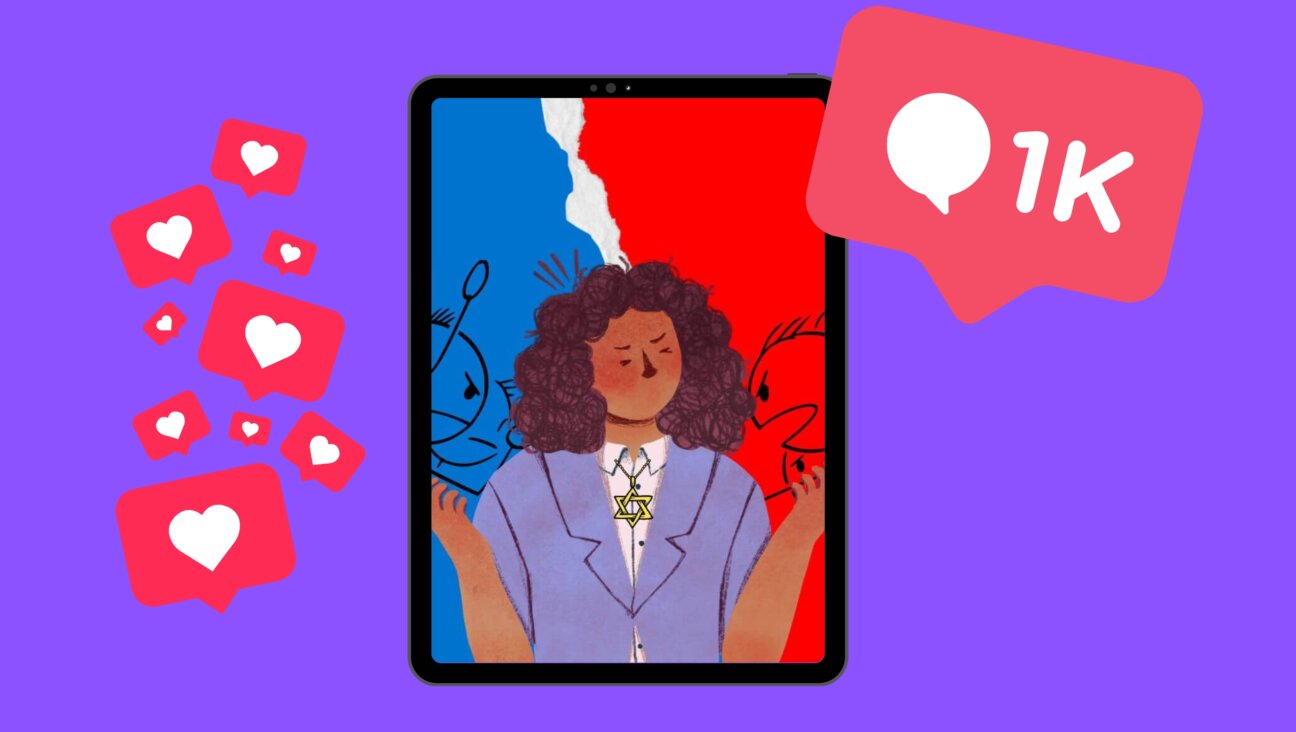

I recently read about Naomi Wadler, the 11 year-old girl who gave an impassioned and fearless speech at last month’s anti-gun rally in Washington DC, only to be picked on by other kids for being black and Jewish. I know exactly how Naomi must feel because 30 years ago, I was Naomi.

I am now a curly head brown woman, yet I started out as a curly head brown girl just like she is now. I had a voice as well, but it certainly wasn’t as loud or strong as hers is. Mine was still trapped in my head, because at that time I didn’t think that there was anything of any value that could come from a kid who was obviously as confused as I was. When I was growing up, black people weren’t as open to new ideas and a black Jew bothered them somehow. My family and neighborhood friends would get angry at me when I’d go to birthday parties and ask what ingredients were in the food before I’d accept a plate. When they’d ask why I had dietary restrictions and I’d share with them I was Jewish, the trouble would start. Now, not only was I the kid who was too good to eat their food, but I was the black girl who wanted to be white because everyone knows there’s no such thing as black Jews. Besides, didn’t I know that the Jews killed Jesus? I was six the first time I had this conversation.

But even as adults scolded me for uttering the words, “I am Jewish,” I never stopped saying them. I knew I had an identity and just because they didn’t see me or understand me, it still didn’t make me see myself any differently, or want to be, anything else.

On my first day of Jewish day school, I noticed that all of the other kids in my class were white. Up to that point, I never even knew white Jews even existed! But these children told me that they weren’t white, though — they were Ashkenazi. Not like me. Even though they were Ashkenazi and Jewish and white, I was still just plain old black to them. Just like the other black people in my neighborhood, in my family. I wasn‘t Jewish; they were.

Nobody ever saw me and said, “she looks Jewish.” I was just always black. A black Jew at best, because if I were just Jewish like all my new friends, how would the world tell us apart? How would the world be able to tell who was the real Jew and who wasn’t? How would the world know that it was ok to mistreat me, if I didn’t let them call me a Black Jew? I had never heard of a black anything else — not a black teacher, a black doctor, or even a black friend. Those designations were unacceptable, but for some reason it was ok to call me a black Jew.

The fact that I wasn’t a real Jew, because there’s no such thing as Jews of African descent, was beaten into my head every day. Each time I heard the word Ashkenazi or even just Jewish, when used to describe my friends, but just “black Jew” for me. It was almost as if calling them white was offensive to them, but somehow, constantly reminding me of my blackness wasn’t supposed to bother me.

I didn’t fit in anywhere. I was too black for the Jewish kids and too Jewish for the black kids. But somewhere in between these two worlds I had a world of my own, one where I could be whatever I wanted to be. And I wasn’t alone because G-d was always with me. It was that spirit that kept me company when I was at Jewish events and no one would talk to me because I was black and I looked “scary,” or when I was at a black event and I spoke funny or wasn’t as cool as someone from the ‘hood should be. It was ok, and it got easier as I got older.

I never fit in growing up and I now do everything in my power to make sure I never will. These days I own my Judaism, my blackness and my voice. I own them because I had to fight for them. They made me cry. They made me wish I were different. They made me sad, but at the same time they were making me strong. Just like Naomi.

If Naomi were my daughter, I would tell her this: let your haters make you strong, you beautiful brown curly headed girl, so you can live the rest of your life victoriously. Make your world everything you always wanted to see in everyone else’s but never did. Pitch the biggest tent you can my dear; I’ve got a feeling you’re going to need the space.