Kosher Sumo

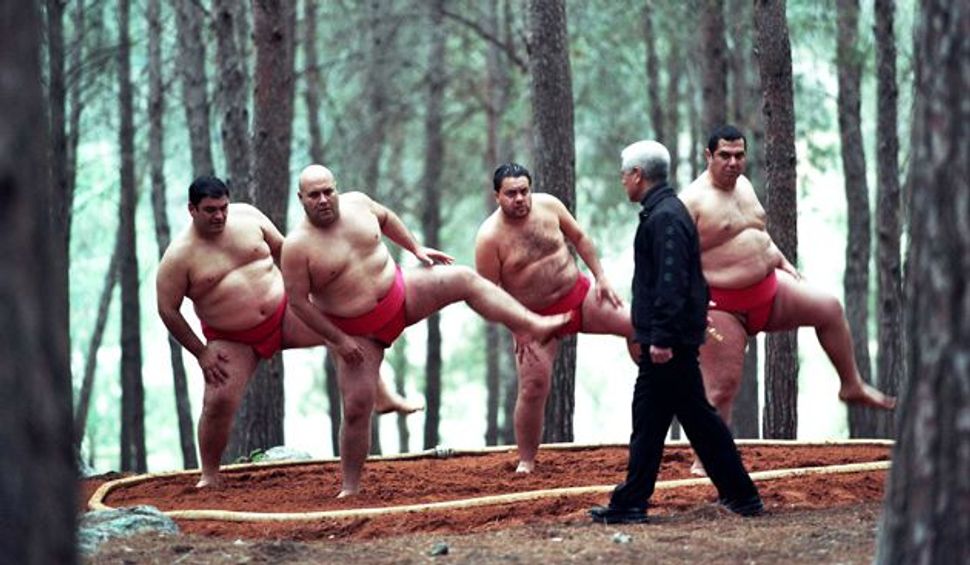

You Put Your Left Leg In: Israeli heavyweight fighters in training. Image by COURTESY OF TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL

‘A Matter of Size” (“Sipur Gadol”) happens to be one of the Israeli entries in this year’s Tribeca Film Festival — but it addresses personal conflict rather than the more stereotypical geopolitical conflict. Directed by Sharon Maymon and Erez Tadmor, the movie tells the story of an overweight Israeli chef who mutinies from the rigors of his diet support group to pursue a field where one can be overweight with impunity: He forms Israel’s first sumo wrestling team.

The film is a comedy, not a documentary, and there can be no denying that it owes debts of gratitude to other cinematic scenarios where “growth through conflict” is sprinkled with humor. The obvious model for “Outsider Receives Asian Tutelage To Overcome His Own Insecurities” is “The Karate Kid,” but Kitano, the group’s appointed sumo sage and sushi restaurant owner, is no Mr. Miyagi; he’s a Makuya Japanese Zionist, of all things (go ahead and Google it; I did). Another familiar trope the film uses is “Beauty Comes in All Shapes,” which “A Matter of Size” shares with the two British films about getting naked — “The Full Monty” and “Calendar Girls.” And finally, of course, there is the inevitable motif recurrence: the getting in shape montage (mercifully short) and the men sauntering along the highway and shuk (marketplace) in itsy-bitsy sumo outfits scene. Okay, arguably the latter is not yet a true cinematic formula, but the Sumo Saunter is a recurring gag in the film.

But, while the film uses sumo on one level, the clichés work because the movie’s real subject has nothing to do with the Japanese sport. What puts “A Matter of Size” in a weight class (forgive me) of its own is its examination of conceptions of physicality within the context of Israeli society — a society based on occasionally brutal candor, the near-desperate desire not to be a “frier,” or “sucker,” and the hardy character of the “sabra.” The plight of the protagonist, Herzl Musiker (played by an expressive and boyish Itzik Cohen), and his four friends, Sammy, Gidi, Aharon and Zehava, is all the more touching as a result. As a child, Herzl is referred to as “Har Herzl” (an allusion to the Israeli mountain), but I’d venture his name was chosen to make clear the parallel between the character and Theodore Herzl, who famously said, “If you will it, it is no dream.” The original Herzl may not have meant sumo, but never mind.

Fat people, the film contends, are people that Israeli society deems it completely okay to hate. True in America, which, ironically, is one of the fattest countries around, it seems doubly true in Israel — an active, appearance-conscious society with that lethal combination of great beaches and mandatory military service. “How come there’s no sumo in Israel?” one guy inquires as the four buddies sit around Gidi’s shawarma joint. “Because there are no fat people in Israel,” Aharon flatly answers, taking another tremendous bite of his shawarma.

Of course, there are the expected scenes of fat-person-rejection-sadness: Gidi’s struggles with online dating, for example, or Aharon’s constant fears of his wife’s infidelity. But where the Farrelly brothers’ film “Shallow Hal” deliberately, and cruelly, plays on its viewers’ prejudices and preconceptions, “A Matter of Size” puts the viewer on Herzl’s side from the very beginning. Herzl is deliberately introduced in the opening scene as a sweet, young, overweight boy waiting to be weighed at school. By the tenth minute when we see the adult Herzl, along with four friends, semi-nonchalantly try to squeeze into the compact for the diet group carpool, they are our buddies. Sure, we like Herzl more than the other boys — who wouldn’t feel for the guy who’s kicked out of the diet group for gaining rather than losing weight? — but we like them all, even with their imperfections.

And the film makes it even easier to sympathize with them, because for the most part, the world around them is filled with real jerks. For example, anyone familiar with Israeli culture — or American Weight Watchers, for that matter — will derive great amusement from the film’s depiction of an Israeli weight-loss “support group.” Where the American equivalent is all about being supportive of one another — “This is your second meeting? Come on, folks, let’s give her a big hand and two stickers!” — Evelin Hagoel’s depiction of Geula, the cold-blooded, chain-smoking Israeli diet facilitator, brings a new dimension to the label “tough love.” Her brutal honesty comes across as nothing less than jaw-droppingly evil. “It hurts me to see you turning yourself into a whale,” she says on Herzl’s answering machine. “Bye-bye, sweetie.”

Geula’s a gem of pure kindness compared with Herzl’s mother, Mona, with whom he lives. Mona couples her regular “You’re getting too fat; I can’t stand to look at you!” comments with the immediate follow-up of: “There’s more couscous in the fridge. Go ahead and finish it.” Mona’s unexpected, piercing meanness (its roots in the circumstances of the death of Herzl’s father notwithstanding) lends more poignancy to the film’s point: For people who are overweight, even love is a double-edged sword. Mona shows that people who are overweight shouldn’t expect to love themselves, or to be loved by anyone else.

Of course, no growth-through-conflict fable would be complete without a love story: Herzl is, in fact, loved. Zehava (Irit Kaplan) meets Herzl in the diet group and there is a spark of genuine attraction. Later, in one of the film’s most emotionally honest moments, Zehava leans seductively in the doorway of her bedroom, clad in only a white silk negligee that strains at her hips and pendulous breasts. In that moment, she could not be more beautiful: She is simply a divorced woman hoping against hope to find love, while knowing that appearances can be deceiving. “I hope you don’t make love with the lights off,” she says — and in her candor, she could not be more attractive, standards be damned. The ensuing playful war with Herzl — lights on, lights off! — is the subject of amusement rather than shame, foreplay rather than forbearance. This, the film says without words, is what the world could promise all of us, Israelis and Americans alike, if we could only let go of our inhibitions and simply be ourselves.

It’s the Israeli “I am who I am” unapologetic spirit that makes this film transcend its formula and the characters transcend their outcast status. Only in Israel, after all, would a boyfriend, upon hearing that a billboard of a girl in a bikini depressed his girlfriend, take it on himself to, shall we say, put an extra few pounds on the billboard with the help of some spray paint. If you will it, after all, it is no dream.

Jordana Horn is a lawyer and writer at work on her first novel.

The trailer for a matter of size is below: