Is the Dialect of Vilna Yiddish the One We Want To Rely On?

Paul Malevitz writes from Los Angeles:

“For well over 70 years now, the standard dialect taught in Yiddish schools has been and still is the ‘northeastern’ one, similar if not always identical to that which was spoken in Vilna. (One difference is that in Vilna Yiddish, veynen can mean both ‘to reside’ and ‘to cry.’ In standard Yiddish, ‘to reside’ is voynen.)

“And yet in 2008, the number of native Yiddish speakers using the northeastern dialect is negligible. There is a small group of Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem, descendants of the students of the Vilna Gaon, who still speak northeastern Yiddish. Chabad Hasidim also do, although in reality, most of them today speak English in America and Hebrew in Israel.

“The vast majority of native Yiddish speakers today are Hasidim of the Satmar, Kloyzenberg, Vizhnitz and other courts, who all use the Central Polish/Southern dialect. (Whereas in standard Yiddish, for example, du geyst *is ‘you go’ and *di gayst [pronounced “DEE GEIST”] is ‘the spirit,’ the latter has both meanings for these Hasidim.) For a number of years, I was a Yiddish interpreter for the AT&T Language Line, and every single call for service that I received was for New York Hasidim, who all spoke the central Polish/Southern dialect. Since learning a ‘living language’ is for the purpose of communication, don’t you think that we need to reassess the dialect of Yiddish we teach in our universities and adult classes to conform to the current reality?”

Mr. Malevitz asks a reasonable question. Certainly, there is nothing sacrosanct about “standard Yiddish.” The northeastern or Lithuanian dialect on which it is based (which was essentially the Yiddish spoken in Belarus as well, but not in Poland, Ukraine, Romania or parts of Hungary) is no more intrinsically superior to other kinds of Yiddish than Parisian French is to other kinds of French, or upper-class London English to lower-class regional English. As is the case with all standard or “official” languages, it acquired its status for purely historical reasons.

With most languages, this happened through the agency of a ruling political class that furthered the dialect of its country’s capital. In Yiddish, however, which had neither a ruling class nor a political capital, the story was different. In the 1890s and the early 20th century, when the idea began to spread among Eastern European Jews that Yiddish was a respectable language with a history and value of its own, and not merely the spoken “jargon” that Jews had traditionally considered it, there were three great centers of Yiddish literary and cultural activity in Eastern Europe: Warsaw, in which a Polish dialect of Yiddish was spoken; Odessa, with its Ukrainian dialect, and Vilna.

Yet a fourth center was in Berlin, where large numbers of Yiddish-speaking émigrés and intellectuals lived. Although any of these could have become the capital of Yiddish linguistic studies, it was Vilna that did when, in 1925, the great Yiddishist Max Weinreich established the Yiddisher visnshaftlekher institute, or Yiddish Scientific Institute, better known as YIVO, in that city. It was YIVO, through the great influence and prestige that it came to acquire under Weinreich’s tutelage, that turned Vilna Yiddish into standard Yiddish, which it has remained in the world of Yiddish scholarship and education to this day. (YIVO itself moved with Weinreich to New York in 1940.)

Hasidism, however, had practically no presence in Lithuania, which was always a bastion of misnagdic or anti-Hasidic Judaism. Nor did the many Hasidic courts of Poland, Ukraine, the Carpathian mountains and Hungary give a hoot about a secular institution like YIVO, or about secular Yiddish culture and literature in general, to which they were and remain bitterly opposed. It is therefore one of the ironies of Jewish history that, as Mr. Malevitz observes, Yiddish has been kept alive as a language transmitted to children from parents only by Hasidim, although not by all of them.

And yet how many American Jews studying Yiddish today are doing so in order to communicate with ultra-Orthodox Hasidim (who, in any case, especially the American-born among them, tend to be perfectly fluent in English)? My guess would be very few. A far greater number are interested in precisely the secular “Yiddishkeit” that the Hasidim reject: a taste of the language or even enough of it to converse with one another in Yiddish clubs, an ability to sing or listen with comprehension to Yiddish songs and to watch Yiddish plays and films, and, for the more ambitious, a command of written Yiddish for the purpose of reading Yiddish literature in the original or engaging in linguistic and historical research.

And if that is your goal, Lithuanian Yiddish is as good a medium as any. It is the Yiddish in which a great deal of Yiddish culture was created, and it is certainly no further removed from most Polish and Ukrainian Yiddish than is the Hungarian Yiddish of many Hasidim. Moreover, once you have learned one dialect of a language, a little effort will enable you to get along in the others. You don’t have to sound like a Satmar Hasid to understand or be understood by him in Yiddish. He’ll be no less happy to talk mameloshn with you if you speak the dialect of Vilna. As accurate as Mr. Malevitz’s description of things may be, there’s no need to revamp an entire educational approach system just to go to di gayst from du geyst.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

- 4

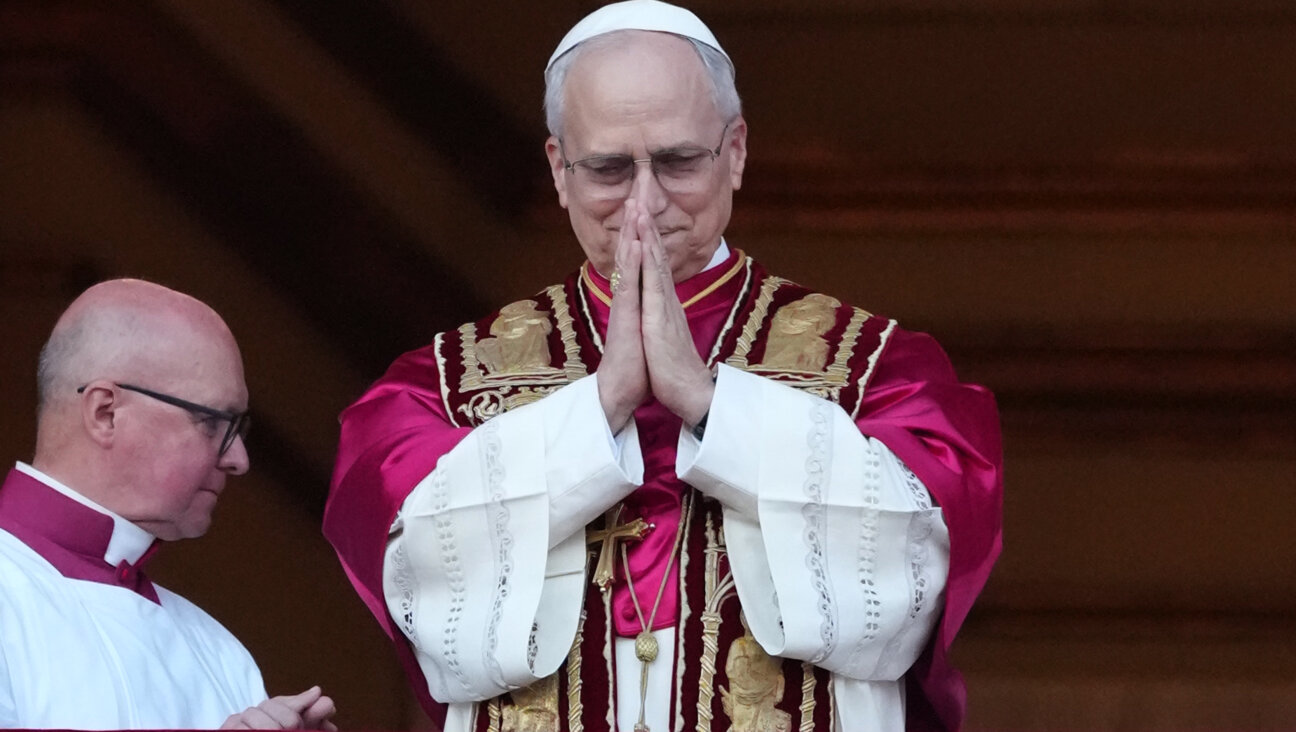

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

In Case You Missed It

-

Yiddish עמיל קאַלינס ראָמאַן אַנטפּלעקט שפּאַלטן אין דער ישׂראלדיקער קאָלעקטיװער נשמהEmil Kalin’s Yiddish novel exposes divisions in the Israeli collective psyche

דער העלד פֿון „צוזאַמענבראָך“ פֿאַרלאָזט זײַן פֿרוי און קינד און לאָזט זיך גיין אויף אַ קאָמפּליצירטן גײַסטיקן דרך.

-

Fast Forward In Tenafly, NJ, a crowd awaits the release of local son Edan Alexander from Hamas captivity

-

Fast Forward Hamas and Trump say Edan Alexander to be freed from Gaza after US negotiates release

-

Culture Should Diaspora Jews be buried in Israel? A rabbi responds

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.