Training Grads for Down Times

Image by Bu photography

Head Start: For college career counselors, getting students into the center is the first step. At Boston University, Daniel Essrow takes the bait. Image by Bu photography

The Class of 2012 will graduate this May with the unique distinction of having begun college when the economy first nosedived, four years ago. But as far as university career centers are concerned, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Many of them revamped their offerings at the start of the downturn, giving them four years to prep and prime graduating seniors on how to navigate the job market.

For colleges with large Jewish populations, their tactics include connecting students with successful alumni, creating industry-specific job fairs, managing student expectations and, in many cases, cluing students in to the fact that career centers exist on campus in the first place.

“One of the things that tends to happen is that students listen to the media so much. When it starts painting these gloomy pictures, students quit going to the career center and almost quit trying,” said Jack Rayman, a 27-year career services veteran at Penn State University, who is now retired. “We felt it was necessary to reach out to them and explain to them it is not as gloomy and not as bad as it seems.”

Though the economy might seem dismal to a first-time job hunter, graduating seniors might actually have it better than their out-of-work counterparts in the real world. For one, individuals with college degrees fare better in economic downturns than those without. According to December’s Bureau of Labor Statistics figures, the unemployment rate for college-educated workers is less than half (or 4.1%) that of high school educated individuals (8.4%).

And over the past few years, things have been looking up — if only slightly so — for recent college graduates. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, about 41% of last year’s graduating seniors who applied for jobs received offers, a 3% uptick from 2010. But the number of students who had secured jobs by graduation held steady at a grim 24% over the past two years — a considerable decline from 2007’s rate of 50%.

What’s more, liberal arts students may actually have a tougher time lining up employment than their vocational and professional counterparts. According to NACE spokesperson Mimi Collins, liberal arts students tend to find jobs after they graduate while other students line them up beforehand.

The reality makes a potent case for college career centers, which now aim to connect with students almost as soon as they arrive on campus. But in order to successfully shepherd students through four years of job prep, they must first make themselves known on campus, a task that is more daunting than it sounds.

“I think that there are many students who don’t come to us and who have concerns about the economy, or their parents do,” said Eleanor Cartelli at Boston University’s Center for Career Development. “They think that there aren’t really jobs, which isn’t the case.”

At Boston University, the career center will soon get a major boost on campus, when it moves to the sparkling new student services building slated to open in September. Along with creating a new website, the center has hired new staff, bringing on Cartelli as the career center’s first marketing and communications director — an unusual position in a college career office. But talking to reporters is just a sliver of Cartelli’s work.

“My team’s main responsibility, our mandate, is to raise our profile on campus, to make sure students understand and are aware of the resources we have for them, whether it is in person or online,” said Cartelli. “We really try to demonstrate to students and showcase to students why there is a career office, where we are, how to use us and the value of doing that.

Meet and Greet: Industry-specific career fairs, like this one hosted by Brandeis, are becoming more common. Image by mike lovett

Brandeis University has also hired a public relations guru in its career center. “Their job for the most part is to do outreach to employers, to help us brand ourselves to employers and to the students,” said Joseph Du Pont, dean of career services at Brandeis.

Since the recession, Brandeis has changed a number of things, including the way it organizes career fairs. “We got rid of our traditional career fairs, these two big ones we had annually, and we went to 12 smaller career fairs that were themed by student and employer interest,” Du Pont said.

Brandeis senior Max Notis took advantage of these targeted career fairs when he went to a law-themed one as a sophomore. But Notis came away disillusioned with the field — instead of meeting potential employers, he encountered Brandeis alumni with law degrees who, like so many of their peers, were out of work. “It wasn’t very productive because everyone was doing terribly,” he said.

The experience was a wakeup call for Notis. Since then, he has changed his focus to advertising, and Brandeis helped him land an internship at an advertising firm in Boston. “Brandeis has been very helpful when I sought help, but it is a tough market,” said Notis, who hopes that his internship will lead to a job when he graduates in May. “To an extent, I feel like they don’t want to get your hopes down too much.”

DuPont said that Brandeis’s career coaches try not to be overly encouraging about job prospects, urging students to think about alternate paths in case their dream jobs don’t pan out. “It is that fine balance. You want people to be realistic, and we are very candid with students and want to have credibility with them,” he said. “It is a balance between being a cheerleader and a coach and being realistic about the possibilities.”

Brandeis, among other schools, has also solidified its alumni network in the wake of the recession, making sure its current students avail themselves of built-in contacts. For instance, when a current student applies at a company where an alumnus works, sometimes the alumnus will conduct the first interview.

At Barnard College, the all-women’s school in New York City, students at any class level are matched with alumni in an optional year-long mentoring program initiated after the recession began. Beyond career contacts, the program helps students — liberal arts majors often without a clear idea of what’s next — hone their ambitions.

“One thing we found at Barnard is that many students are unsure of what they want to do, and we found that when students are figuring this out, alumni are critically important,” said Robert Earl, the head of career services.

The most important thing to guarantee post-grad employment, career center directors said, is for students to start job hunting early — as in, today.

“A lot of people think the degree is a guarantee of employment,” said Rayman, of Penn State. “But the reality is it is a hunting license. It allows you to go out there and find something.”

Naomi Zeveloff is a Forward fellow.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

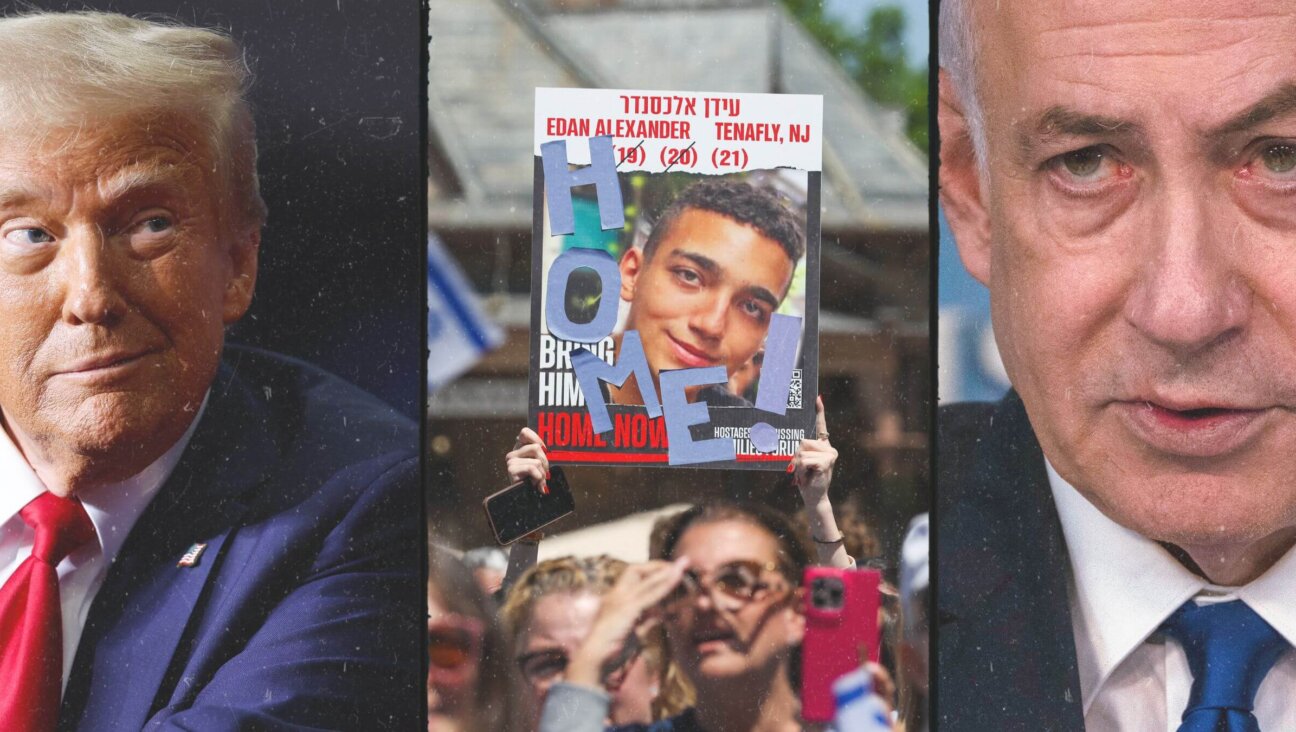

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.