Michael Feinstein Strikes Up The Bland

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Gershwins and Me

By Michael Feinstein

Simon & Schuster, 320 pages, $45

George Gershwin is widely, and rightly, regarded as a quintessentially American character. This isn’t merely because of the way his music sounds; while the music he wrote is unmistakably American, the same can be said for any number of other American composers of the 20th century, both classical and popular, just as French composers usually sound recognizably French, Russian composers Russian, Hungarian composers Hungarian, etc. No, it’s the circumstances of Gershwin’s life that are unique to this country. A poor boy, son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, raised rough on the streets of New York’s Lower East Side, with little formal education, destined — at least in his own retelling — to end up as a gangster, he discovered music almost by accident, teaching himself to play by ear on a neighbor’s piano. When his parents bought a cheap upright so his older brother could have lessons, he astonished the family by sitting down at the instrument and performing.

A disproportionate number of American songwriters contemporaneous with Gershwin were second-generation Jews from the mean streets of New York. Most of them lacked formal conservatory training, and many were even effectively illiterate, musically speaking. What distinguishes Gershwin from the rest, and makes his life story so characteristically American, is the way he transformed himself from Tin Pan Alley tunesmith (primarily working with his lyricist brother, Ira) to something beyond. Despite a very haphazard technical background and little encouragement, he went from being a first-rate songwriter to a composer, working with growing confidence in longer forms, employing an increasingly complex harmonic vocabulary, and, with growing mastery, sustaining intricate classical structures. He was not the only one of his colleagues to attempt this transition — Cole Porter assayed a ballet, Richard Rodgers a tone poem — but he was the only one to do it successfully. At least four of his large-scale compositions have found a permanent place in the standard classical repertoire. And in the last couple of decades, “Porgy and Bess” has won overdue recognition as a real opera, not merely a collection of great songs with annoying recitatives shoved in between. Anyone doubting its influence would be advised to compare it, on an almost scene-by-scene basis, with Benjamin Britten’s landmark opera “Peter Grimes.” The young Britten saw “Porgy” during its initial run in New York, and, although the British composer’s diary mentions the fact without further comment, we can assume that the impact was lasting, if subliminal.

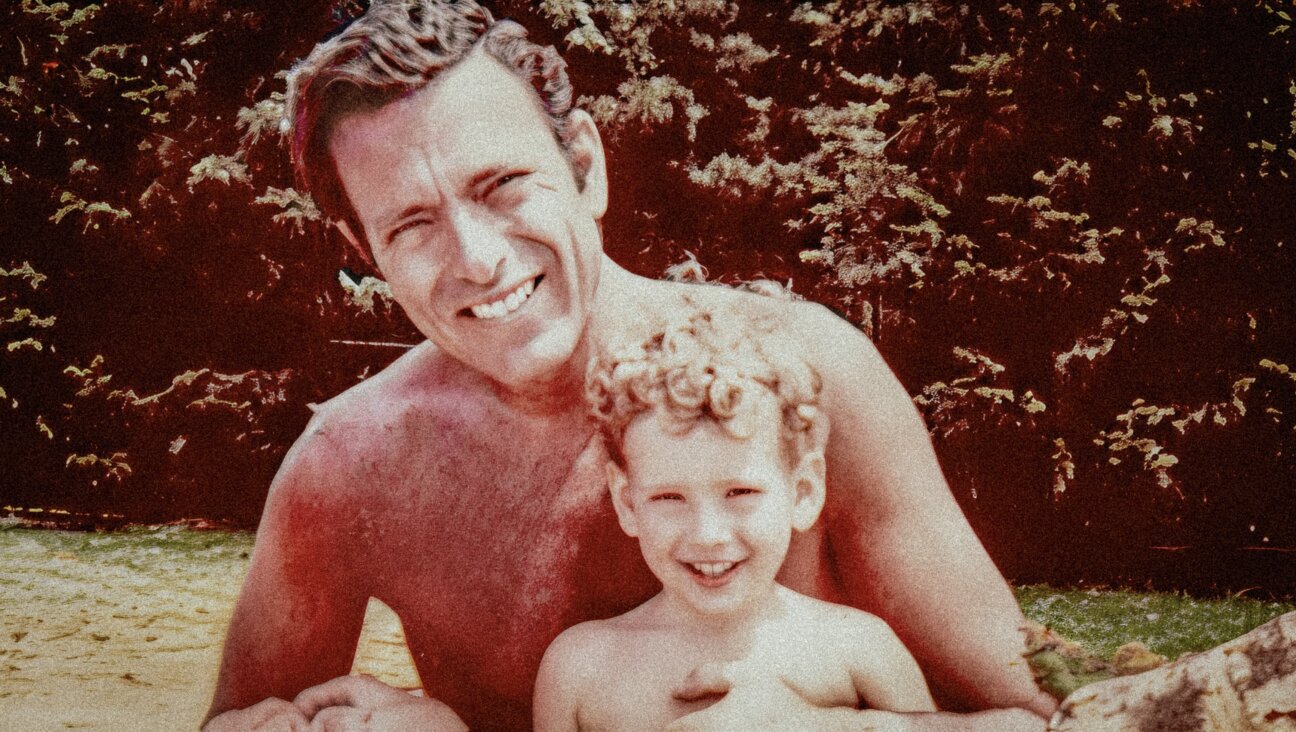

The performer Michael Feinstein idolizes both Gershwins. And he has a personal connection: He served for several years as Ira’s assistant, which, in practice, meant private secretary, archivist, oral historian, house pianist, meal-time companion and virtual member of the household. Feinstein’s new book, “The Gershwins and Me,” is a sustained act of homage. What it is not, unfortunately, is a sustained act of book writing.

Onstage, Feinstein is a genial and ingratiating presence, and he has produced a genial and ingratiating book. But it is sufficiently disorganized that one finds oneself puzzled even about its basic intent. Why did he write it? For what audience is it intended? What is it meant to add to our knowledge of, or feelings for, the Gershwin brothers? The author’s devotion to the Gershwin legacy is self-evident, and there can be no doubt about his love for the man who became something of a surrogate father to him. But if the book is more than a testament to those laudable sentiments, I am unable to discern what that is.

Feinstein’s book is part (and partial) biography, rehashing some of the highlights of the brothers’ lives, omitting many others. But there are enough biographies of George, if not Ira, that, without important new information to impart, another biography is supererogatory. (And it’s frustrating there is so little new information, since for many years Feinstein had unfettered access to Ira Gershwin’s gargantuan assemblage of documents, which it was his job to organize and catalogue.) It’s also part musical analysis, part psycho-history, part disquisition on musical culture in general, part idiosyncratic assessment of Gershwin’s contemporaries and their work, part history of the American musical theater and part personal memoir. But it’s not thoroughly or satisfyingly any of these things. It is, to use a word with which both Gershwins would have been familiar, a mishmash.

Probably the most disappointing sections are those for which one had the highest expectations, the discussions of Gershwin’s ouevre. Feinstein is a superb musician himself, but whatever technical insights he might be capable of providing he eschews in favor of descriptions like this:

“Gershwin might have used the same language and the same notes as other musicians, but he created unique music — music with a spiritual quality, a warmth, a humanity to it. “Any great art inspires us to dream of achieving greater heights. With its extra magic, Gerswhin’s music enthralls and touches people in a way that is unlike the effect of any other composer…”

Does this illuminate anything? There are many passages along these lines, and all they tell us, finally, is “I love this stuff.” Writers as diverse as Daniel Francis Tovey, Joseph Kerman, Charles Rosen, Gunther Schuller (writing about jazz improvisation) and Wilfrid Mellers (writing about the Beatles) have demonstrated that words can bring music to life and can even go some distance toward explaining its workings. Aaron Copland, in one of his books, devotes a few sentences to Gershwin’s “Fascinating Rhythm” and explains, in a way comprehensible to laymen, what exactly makes its rhythm fascinating. That’s the sort of thing Feinstein rarely even attempts.

Where he’s most entertaining, and most interesting, is in the personal passages, the gossip and opinions and anecdotes. This material isn’t always especially relevant — much of it has nothing to do with the Gershwins — but it has the flavor of real conversation, the tang of a critical mind and sharp tongue in action. Minority opinions about such songs as “Night and Day,” “Over the Rainbow” and “All the Things You Are” are refreshing even if one disagrees with them, a welcome tonic to the book’s general tone of piety.

Stories, some unflattering, about Mickey Rooney, Ethel Merman, Fred and Adele Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart and Oscar Levant, along with speculation about George Gershwin’s sex life, are fresh and lively and at least slightly heretical. And his discussion of Lenore Gershwin, Ira’s infamous wife, is, in its modest way, eye-opening. Generally portrayed as an irredeemable harridan, she was certainly not, in Feinstein’s account, any carefree frolic in the park. But he humanizes her without smoothing over her very rough edges, lauds her devotion and loyalty to her husband and provides us with the most comprehensive portrait of her I’ve encountered in print. And all this despite obviously not liking her very much.

The book comes with a CD of Feinstein performing a selection of Gershwin songs. Alas, the CD was lacking in my review copy. But even without hearing it, I’d wager the CD tells us more about the glories of Gershwin’s music than the text it accompanies.

Erik Tarloff has reviewed music, books, and theater for The New York Times, Slate, The Washington Post, The San Francisco Chronicle, and many other publications. His novel “Face-Time” has just been released as an ebook.