The Sheynest Punim of Them All

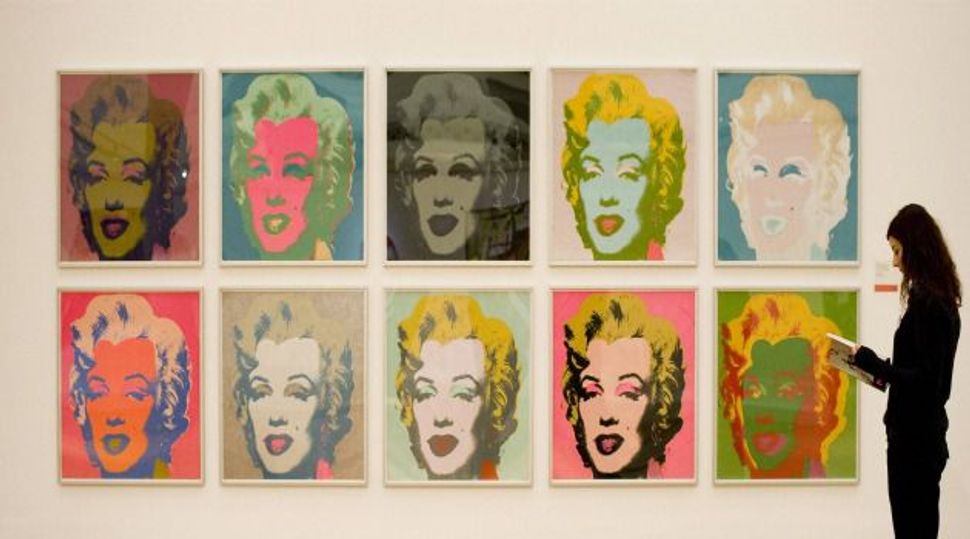

Beautiful Faces: Andy Warhol?s many punims of Marilyn Monroe Image by Getty Images

When does a word borrowed from another language officially become a member in good standing of American English? Some might say that this happens only when it is included in the dictionaries. Yet new dictionaries are not published every day, and even when they come out, they often overlook words that have been regarded for years by many English speakers as part of their vocabulary. A better test might be when a borrowed word first appears in a reputable publication without italics, quotation marks or parenthetical explanations — and what more respectable publication could there be than our august New York Times?

Welcome to the language then, punim! That’s p-u-n-i-m, pronounced PU-nim, with the “u” like the vowel in “foot,” as in a passage like:

“The digital photography revolution roughly coincided with the births of my two daughters…. For a while I kept up with the sorting, naming, uploading and ordering (and editing) of prints…. It was some time in 2009 that I nearly stopped taking pictures of them, since the very thought of new images of their grinning punims became synonymous in my mind with hard labor.”

That’s from a December 1 Times op-ed titled “Many More Images, Much Less Meaning,” by author Lucinda Rosenfeld. No one at the Times, it would seem, raised an eyebrow over “punim,” or thought it called for special treatment or explanation, much less for being replaced by a more understandable slang word like “mug” or “puss.” It passed the Times’ editorial desk, one might say, with flying colors. Although its Yiddish plural is penimer, Ms. Rosenfeld quite sensibly opts for “punims,” since she is, after all, writing English.

It’s a good Yiddish word, of course, even if some of us might prefer “ponim,” especially if we hail from Litvish — that is, from Northeastern Yiddish-speaking — stock. It comes from Hebrew panim (pah-NEEM), “face,” which remains panim in the plural, since it is already a pluralized noun in the singular, presumably because the face has two symmetrical halves.

To Yinglish speakers, “punim” (which is the way I’ll spell it, despite its going against my Litvish grain) is hardly a new word, though it was never one used by them freely. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an American Jew say anything like, “Go wash your punim,” or, “I don’t want to see your punim again.” Indeed, “punim” in Judeo-English is almost entirely restricted to the phrase “[a] sheyne punim” — literally, a pretty or beautiful face. Most often this occurs as an expression of endearment, especially with children. “Sheyne punim!” a mother will say to her 2-month-old, in the sense of “You little darling, you!” “Sheyne punim!” you coo to the little creature in your neighbor’s baby carriage, which doesn’t mean you really think it’s all that beautiful.

In a variety of spellings (shayne, shana, shaneh), sheyne punim has been around in the American media for a while, sometimes italicized and sometimes not. What’s happened recently, however, is that “punim” has become decoupled from this combination and begun to occur in American English by itself. Usually, you’ll find it in a breezily written passage in which it’s meant to add to the with-it ambience. Here, for instance, is Steven Weber, writing in The Huffington Post in 2009:

“Between the menacing acronym TARP and the gag-inducing Nadya Suleman, AKA Octopussy, the latest credulity-straining events to occupy both ends of the cultural spectrum, we are still living in an Ian Fleming carny world and the always trusty media, ready to amass an unthinking crowd of agreeable consumers, barfs the data like a barker all over our passive punims.”

And here’s fashion writer Marshall Heyman in The Wall Street Journal in 2011:

“Sometime between midnight and one in the morning at the V Man party on Tuesday at the new Mondrian in SoHo, $5,000 in cash dropped from the ceiling as Kanye West (the magazine’s current cover star) and Stephen Gan (the magazine’s creative director) looked on. The $5,000 was mixed in with another $5,000 in fake bills featuring Mr. West’s punim.”

What’s curious about this is that it hasn’t involved imitation. Most Yinglish words that have entered general American speech — schlep, maven, chutzpah, etc. — have done so by a process of non-Jewish speakers picking up the word from Jewish speakers and circulating it among their non-Jewish acquaintances. Yet “punim” in the language of writers like Weber and Heyman has nothing to do with Judeo-English usage. American Jews never inserted “punim” into their speech in this way. We seem to be witnessing a purely written phenomenon in which “punim” is being used for literary effect. Almost always, spoken slang precedes written slang. It will be interesting to see whether in this case the process is reversed and “punim” eventually takes on a spoken existence.

Meanwhile, proceed with caution. The New York Times notwithstanding, “punim,” I’m told, still hasn’t been recognized as a valid Scrabble word.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]