Tending Bar and Talking Faith With Jewish Drinking Columnist Rosie Schaap

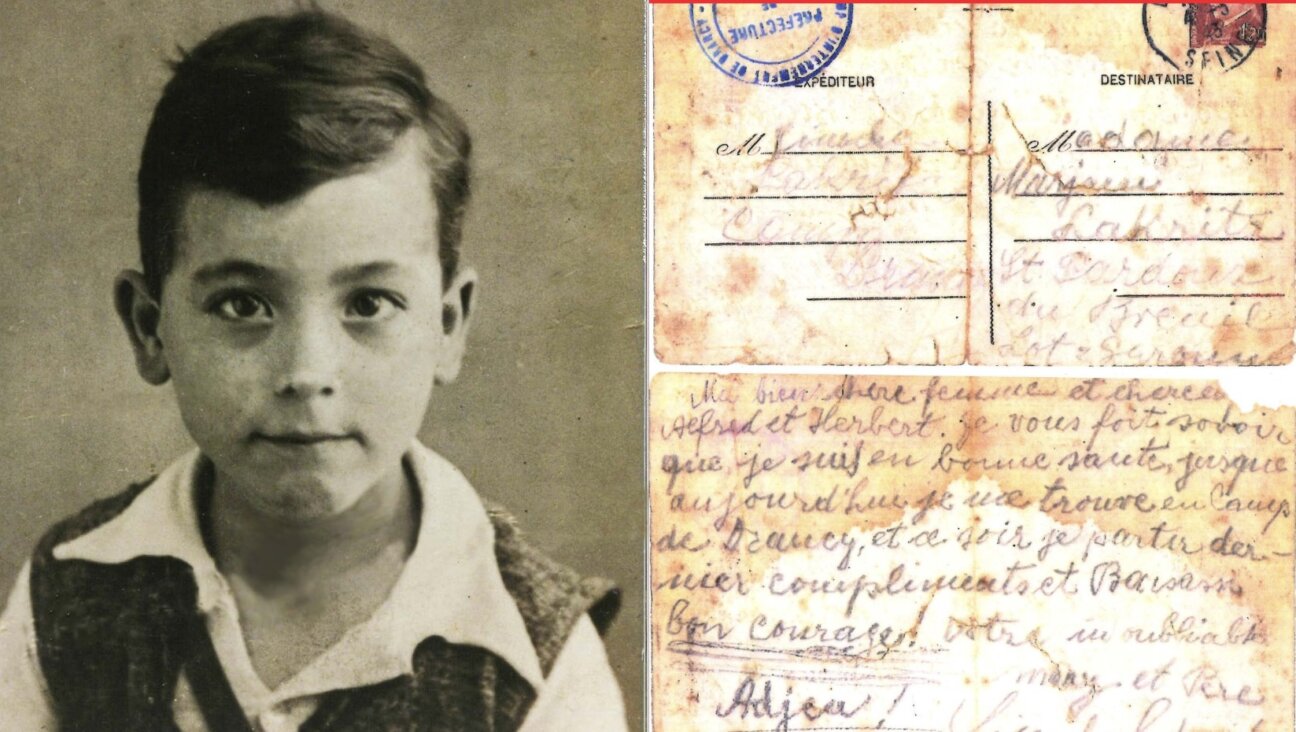

Here Comes A Regular: In addition to writing and bartending, Rosie Schaap is also the chaplain of Fish Bar. Image by M. SHARKEY

● Drinking With Men: A Memoir

By Rosie Schaap

Riverhead Books, 272 pages, $26.95

As Rosie Schaap remembers it, in 1987, at the age of 16, she took the advice of her guidance counselor and dropped out of high school to follow the Grateful Dead. She sold beads and tie-dyed T-shirts to support herself, went to Dead concerts around the country, smoked pot and drank alcohol.

In one dizzying and graphic scene from her witty new memoir, “Drinking With Men,” Schaap came to in a motel room after doing 21 shots of Jack Daniel’s at a bar in Los Angeles. “That was a real binge,” said Schaap — now the Drink columnist for The New York Times Magazine — tending bar at South near her home in Brooklyn. “It was by far the most I have ever drunk. The next day, when I woke up, it took me a while to realize that I was in Santa Cruz, 350 miles away from where I drank the shots. There were dangers, but youth makes you forget that. I am grateful I am not dead.”

Schaap’s precocious bourbon experience is part of her 25-year chronicle of her life in bars — often as one of the few women regulars — and a gimlet-eyed exploration of modern bar culture.

I met Schaap on a freezing winter day, but South, which is Schaap’s local, provides a warm and welcoming oasis in the gritty Polish and Mexican neighborhood of Greenwood Heights. “Becoming a regular at your local bar can just be the decision to engage,” the 42-year-old Schaap said over a pint of Guinness. “If you develop a quick rapport with the bartender, it is like having an endorsement or a referral. I also say things that bartenders rarely hear, like ‘Please,’ ‘Thank you’ and ‘How are you?’”

Schaap is the daughter of the late, great sportswriter and ESPN broadcaster Dick Schaap. She was raised in Manhattan until her parents’ divorce, when she was 7, and then grew up in Connecticut.

“My parents were very secular,” Schaap said. “If we made it to Yom Kippur services once every three years, we got a big pat on the back. I was always interested in religion, though.” She recounted memories of attending services at a hippie synagogue one summer on Fire Island by herself when she was 8. “I think we are just hard-wired for certain things,” Schaap noted.

Schaap bartends once a week. As the late-afternoon light faded, young regulars started coming in after work and greeting her, some reaching over and hugging her. In the background, Roger Miller’s “You Can’t Rollerskate in a Buffalo Herd” played on the jukebox.

Schaap’s book begins with her wild childhood. At the age of 15, heading back to Connecticut after visiting her therapist in New York City, she would read Tarot cards to commuters in the Metro-North bar car in exchange for beers. Then there was the near-fatal Grateful Dead experience. She wound up at Bennington College, in Vermont, and went on to study in Dublin. “I was mistaken for being Irish,” Schaap said. “Part of it had to do with the stereotype about drinking.”

“Drinking With Men” profiles the eight major bars that forged Schaap’s life. She says that a Lower Manhattan dive named Puffy’s Tavern changed her relationship with bars. “It was 1996, and I was 25,” Schaap said. “I was a grad student in English. I would go to Puffy’s, have a Guinness at a banquette and grade papers. The regulars left me alone. I enjoyed eavesdropping on their good-natured joking around.” Finally, something clicked for Schaap. “I can almost see this moment in slow motion,” she said. “I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve graded enough papers.’ I went to the bar and started talking to people. It was the single most intense period of bar patronage in my life. I was there every day.”

Schaap bonded with her fellow regulars and learned about bar romances and one-night stands. Puffy’s, however, was prone to dark nights, where the despair of struggling artists could become palpable. “An older artist friend asked me why I was hanging out at the bar,” Schaap said, “and should I really be doing this at my age? He didn’t want me to still be at Puffy’s 15 years later. That did make me think: Is this a healthy environment for a 25-year-old to be in? I aged a lot in that year, but I don’t regret a minute of it.”

While Schaap was spending all her time at Puffy’s, her relationship with her roommate, Vanessa, an old college friend, was falling apart. One day, Schaap found the woman’s diary and read an entry about herself.

“Seeing my roommate’s diary was very upsetting,” Schaap said. “She said I was an alcoholic. That really did freak me out. I had to think about whether I was one. I’m not. It’s really easy for me not to drink, but for part of my life, it was very hard for me not to be in a bar. What do you do in a bar? You drink.”

Over the years, Schaap has cut back on her drinking. “Right now, three drinks are good for me. I have lost my tolerance. Some people I know keep on drinking a lot anyway and deal with the hangovers, but I can’t.”

Eventually, with some other Puffy’s regulars, Schaap shifted her loyalty to a nearby bar called Liquor Store, where she found the conversation more scintillating. “For me, Liquor Store was the sweet spot,” Schaap said. “It reminded me of what the European cafe society in my imagination might be. You might start with two people at a table, but by the end there would be five more people at the table, with everybody frantically smoking, talking and joking.” When she got involved with her future husband, Frank Duba, she brought him by the bar for her drinking companions’ approval.

After Liquor Store closed, Schaap and her husband moved on to the East Village’s Fish Bar, a tiny establishment run by her friends. At this time, Schaap pursued her interest in theology.

“It is all really hard to explain,” Schaap said “There was a time I thought I’d become Christian because of [the poet] William Blake. What I wanted doesn’t exist, something that encouraged questioning. This is what I value about Judaism… the story of Job and God is the classic Jewish relationship. The whole idea is that we can rail against God.”

“I am possibly one of the worst representatives to speak on behalf of Judaism, but there are not many of us, and it is one of the amazing facts of history that we are still here. I may never be an observant Jew, but I could not not be Jewish.”

Schaap took a two-year ordination course to become a minister. “It definitely taught me about what I didn’t believe in,” she said. “The course was warm, fuzzy and therapeutic, but I wanted something more rigorous.”

Schaap’s studies were interrupted by the 9/11 terrorist attacks. She volunteered with the Red Cross, eventually becoming a chaplain, ministering to the family members of those killed.

“The Red Cross had a great training,” Schaap said. “They said: ‘Don’t tell anyone that September 11 is part of God’s plan. Just let the families lead you.’”

Schaap subsequently became the chaplain at the Fish Bar. “People knew I had been ordained,” she said. “A bartender put up a sign that said, ‘The Chaplain Is In/The Chaplain Is Out.’ I didn’t say things like ‘Well, my son,’ but there are many easy comparisons between bartending and ministry. It was such a small bar; we all knew each other’s business. I would occasionally sit with people who had spiritual issues, but that didn’t happen a lot.”

At the end of our interview, the sun had completely set and all the seats at the bar were filled with regulars, both hipsters and locals. Schaap stepped behind the bar to pull a pint of Guinness for the establishment’s owner.

When she bartends at South, Schaap occasionally sees women who remind her of a younger version of herself. At the end of her memoir, she notices a young woman who knits by herself in the corner for several weeks until she steps up to the bar, eventually becoming a regular.

“I don’t give advice to the customers, but if I see someone screwing with them, I’ll break that up,” Schaap said. “That is what’s expected from a good bartender. Nobody gave me any advice. No bartender ever said: ‘Here you are, a girl hanging out in a bar. Don’t go home with So-and-So,’ or, ‘Don’t have that last Jameson.’

“When I see a person truly hammered, I will put them in a taxi or have (someone) walk them home, but it is not my job to tell them how not to screw up their lives in a way that might make them more interesting.”

Dylan Foley is a freelance writer in Brooklyn. He is working on a history of postwar bohemians in Greenwich Village.