How Bob Dylan, Barbra Streisand and Lenny Bruce Changed Judaism Forever

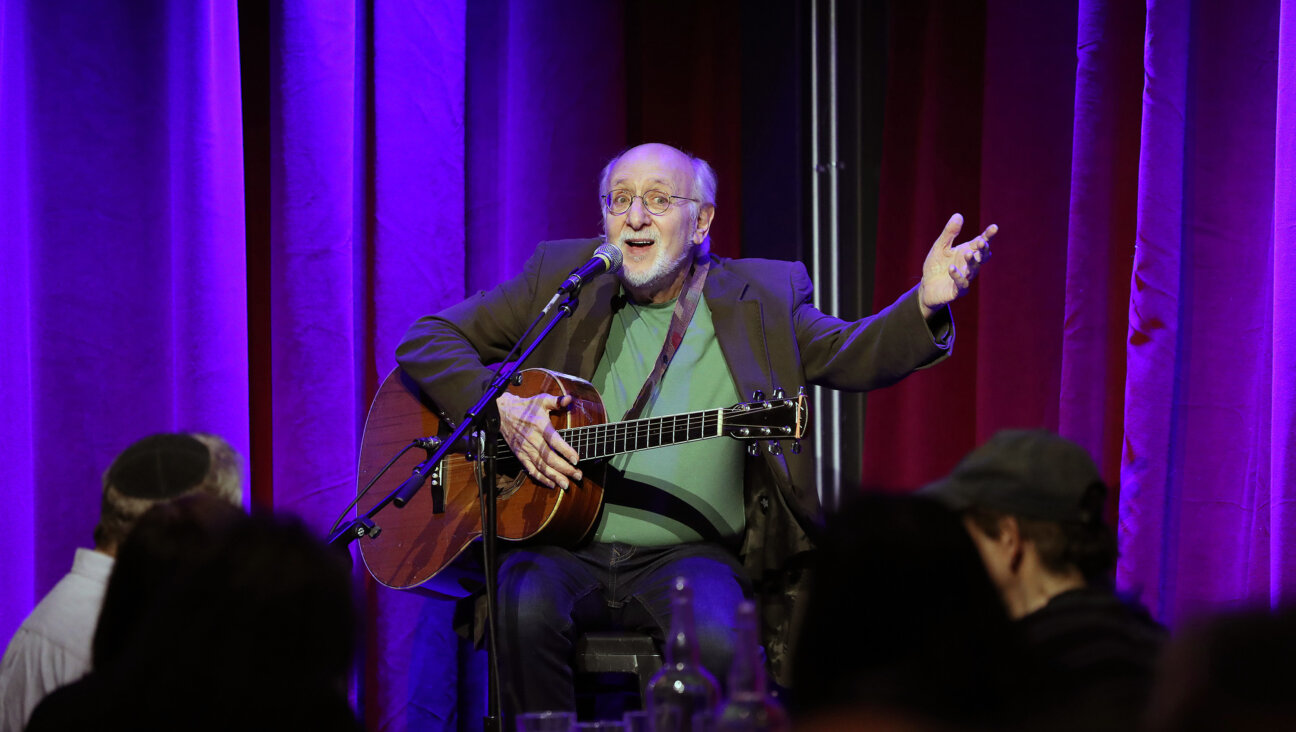

The New Face of Judaism: David E. Kaufman?s new book argues that Bob Dylan was one of four artists in the 1960s who helped usher in a new era for Jews. Image by Getty Images

● Jewhooing the Sixties

by David E. Kaufman

Brandeis University Press, 360 pages, $36

The final week of September 1961 proved to be an auspicious one in American Jewish history — or, at least, in the history of Jewish-American celebrities.

Within a matter of just a few days, Sandy Koufax set his first National League strikeout record; comedian Lenny Bruce was arrested on obscenity charges; a then-unknown folksinger named Bob Dylan would play an opening set for the Greenbriar Boys at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village that would capture the attention of a reviewer for The New York Times; and a 19-year-old cabaret singer named Barbra Streisand made her off-Broadway debut.

The rest, as they say, is history, as well as the launching pad for David E. Kaufman’s “Jewhooing the Sixties: American Celebrity and Jewish Identity.” An associate professor of religion, and the Florence and Robert Kaufman Chair in Jewish Studies at Hofstra University, Kaufman suggests that the approximately simultaneous rise to fame of these four third-generation American Jews was “a turning point in the history of both American celebrity and Jewish identity.”

He likens them to postwar American Jewish culture’s “Mount Rushmore of fame,” whose achievements would go on to “reshape the image of the American Jew” for both Jew and non-Jew alike.

These four were by no means the first of their kind. One could easily rattle off several lists of Jewish forebears who blazed trails beforehand, including baseball star Hank Greenberg; comedians including Groucho Marx, Jack Benny and George Burns, to name just a few; musical theater stars Sophie Tucker and Fanny Brice; and in music, Benny Goodman and Irving Berlin.

But as Kaufman goes to great lengths to argue, this quartet was more transformational than those who came before, both in their personal identity as Jews and in what they represented to Jews and society at large as Jews.

Koufax, the aloof sports hero, was a new kind of Jewish man, “embodying the cool masculinity of the Hollywood antihero.” Bruce was the apotheosis of Jewish rebellion against the status quo. Streisand overturned prevailing notions of female beauty, sexuality and stardom. Dylan refused to abide by any preconceived notions of identity, whether Jewish, musical or otherwise. In sum, “these four created their own rules, and helped usher in a new era for all American Jews.”

Kaufman’s study in large part examines the contemporaneous, and by now, historical notions of who these celebrities were and what their fame represented vis-à-vis their Jewishness.

This is the “Jewhooing” aspect of the book’s unfortunate title, the origin of which is never completely explained. I, for one, grew up in an extended family that greatly enjoyed playing “name that Jew,” but never heard the term “Jewhooing” until I read this book.

While it’s clear how this group represented a new way of being both Jewish in public as well as famous — Koufax in his very public refusal to play ball on the High Holy Days, even when it meant sitting out a World Series game; Bruce in his in-your-face use of Yiddish obscenities; Streisand in her embrace of Jewish roles from Fanny Brice to “Yentl”; and Dylan in his caginess about his background and belief system — it’s not always clear just how this translates into the lives of the American-Jewish everyman who is not famous (beyond instilling the same sort of pride that came out of the “Jewhooing” game of decades past), nor is it clear what any of this has to do with the ‘60s. other than that it all took place in that decade.

After all, when talking about the “celebrity culture” of the ‘60s, one must take into account the role of such non-Jewish figures as John F. Kennedy, The Beatles, Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King Jr., and Raquel Welch.

Kaufman digs deep into media coverage of the time to explore just how the Jewish background of this mosaic quartet was treated, and he is on solid ground here, especially regarding Koufax, Bruce and Streisand. His analysis of Bob Dylan as an uber-assimilationist, however, is less convincing, and here is where full disclosure requires me to note that the author interviewed me for his book and spends a few paragraphs detailing how my own book on Dylan is an example “of the kind of Dylan Jewhooing in which identification is taken to an extreme.” Where Kaufman finds Dylan’s name change and his inventive stories about his background representative of his mutable identity, he finds the very same tendencies in Streisand’s early career — changing her name from Barbara to Barbra, claiming to have been “born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon” — as merely playful “tomfoolery.” Perhaps another case of “extreme identification”?

Kaufman writes, “Both Jews and celebrities are in a sense ‘chosen people’ — seemingly ‘chosen’ by some higher power, but at the same time ‘people’ like everyone else.” It could be argued that both Jews and celebrities are in fact not viewed as “people like everyone else,” and that, more than anything, might go far to explain the odd phenomenon of “Jewhooing.”

Seth Rogovoy is the author of ‘Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet’ (Scribner, 2009).

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture How one Jewish woman fought the Nazis — and helped found a new Italian republic

-

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

-

Fast Forward Betar ‘almost exclusively triggered’ former student’s detention, judge says

-

Fast Forward ‘Honey, he’s had enough of you’: Trump’s Middle East moves increasingly appear to sideline Israel

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.