Stacy Horn Preaches To the Choir

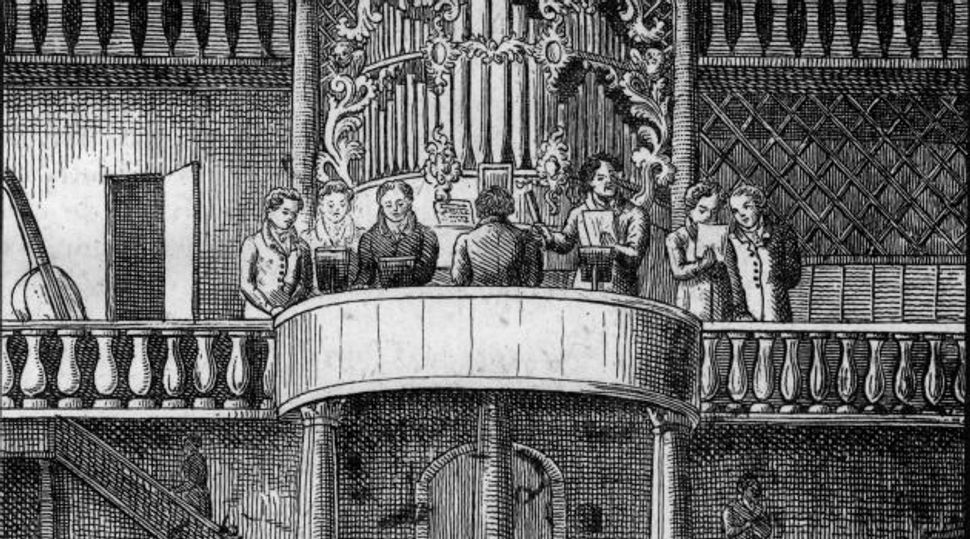

I?d Like To Teach the World To Sing: Stacy Horn?s ?Imperfect Harmony weaves in her own experience with singing in a chorus with historical anecdotes about choral singing. Image by Getty Images/Hulton Archive

IMPERFECT HARMONY: FINDING HAPPINESS IN SINGING WITH OTHERS

By Stacy Horn

Algonquin, 256 pages, $15.95

During my high school and college years, I used to joke that if there was a church on an Ottawa, Ontario, street corner, I probably sang in it. The joke came back to me while I was reading Stacy Horn’s new book “Imperfect Harmony.”

I was raised according to Modern Orthodox tenets, still observed the Sabbath and all the holidays, and wasn’t terribly rebellious about religion. (That came later, after moving to New York.) But for a serious music student, which I was at the time, the way to prove yourself on the local level was to sing in competitions, and those were held in churches.

Winning or placing depended as much on talent and music choice as it did on the performance acoustics, which ran from stunning to downright awful.

My church knowledge really got going, though, when I joined the Ottawa Regional Youth Choir at the age of 15. I’d sung in a choir at my Jewish day school, my childish ego augmented by some solos I did deserve and many others I didn’t, but the moment I opened my mouth to sing at my first Monday night rehearsal with the ORYC, I knew I was in over my head.

The choir director was stern and demanding, shooting glares if you were a minute late to your seat and ill prepared to sing when the clock struck 7 p.m. The other singers, recent graduates of the middle school chorus that the director also conducted, seemed trained to impeccable, unreachable levels. I wasn’t the only Jew in the choir, but I wasn’t familiar with Christian sacred music, and I was carefully taught, in school and at home, to cover my ears at Christmas carols playing on the radio or television. But the moment I began to sing, my fears disappeared. I was part of something larger. Save for a hiatus or two, I’ve belonged to a choir ever since.

The churches were resonant vessels through which my fellow choristers and I could communicate some of the most awe-inspiring music ever put to paper. Most of the time, joy filled me and strengthened my voice further. Only once, a decade or so ago, did my voice fall into laryngitic despair, after singing both Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony — noto-

riously demanding on sopranos — and Orff’s “Carmina Burana” within two months of each other. But the consequences of hitting those larynx-lacerating high notes in one of Montreal’s oldest and most acoustically pleasing churches paled when compared to being part of a continuum of music-makers stretching back over two centuries.

From the menacing thrill of the “Dies Irae” in Mozart’s “Requiem” to the expansive hope of David Berger’s spin on “Hatikvah” — to name two of my favorite pieces — choral music allows me to access emotions that cause me trepidation in text or in real life. Four-part harmony beats therapy; it pulled me out of the black grief of mourning after my father’s death last year when little else could. And every Monday evening, when I arrive just in time for weekly rehearsal with my current community choir in Brooklyn, the workday fatigue melts away in service of the greater good of learning, perfecting and performing amazing music.

My choral experiences prepared me well to adore Stacy Horn’s “Imperfect Harmony: Finding Happiness Singing With Others,” her fifth nonfiction book and a seeming departure after embedding with the New York City Police Department’s cold case unit (in “The Restless Sleep”) and investigating the paranormal (“Unbelievable”). Horn is a member of The Choral Society, which performs at Grace Church. She first joined in 1982, after the end of a brief marriage and several half-hearted relationships left her “sitting on the floor in the middle of my living room, rocking back and forth and crying about yet another painful breakup.”

Making a list of things that made her happy, Horn called up long-dormant memories of when singing brought joy to her life. Weeks later, nervous that her pitch would go flat, she auditioned for the chorus, which held rehearsals every Tuesday night in the nearly 200-year-old church on 10th and Broadway; she got in, and she’ll remain “in the world that singing reveals for as long and as often as I can.”

Using her experiences with Grace Church as a foundation (and stand-in for community choirs across the country), Horn weaves in many historical anecdotes about choral singing. We learn, through Horn’s warm, breezy prose, about the choral society’s history: transformed from an elite-oriented group to one for the communal masses, irrespective of religion or creed. She sprinkles in past examples of communal music making, from Frank Damrosch’s idealized but short-lived People’s Choral Union for the working class and Francis Boot’s turn of the 20th century desire to fund new choral works, with varying success, to the down-and-dirty 1834 riots provoked by the Chatham Street Chapel group.

The book is strongest when it focuses on the musical process. I’ve never sung Morten Lauridsen’s “O Magnum Mysterium,” but Horn makes a vivid case for why that choral work has wowed audiences and singers since its 1994 premiere: “[T]he music is saying that no matter what there is to celebrate, there’s always this tragedy, this suffering underneath. Or equally true, no matter what tragedy occurs, there is always reason for joy.” As soon as I finished “Imperfect Harmony,” I pulled up a recording of the six-minute piece on YouTube and felt as powerful an urge as Horn’s fellow choristers to sing the piece. Similarly, Horn’s closing chapter description of trying to learn her part for Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir, inspired by a budding teen composer and spurred to fruition after a TED talk, straddles cringe, hilarity and knowing understanding of what it is to expose oneself.

“Imperfect Harmony” also allows Horn to be more candid about her life than she could be in earlier books, since for her, choral singing is intensely personal. And while I certainly empathized with her struggles, whether worrying over how to pay for mounting medical and veterinarian bills on dwindling income and mounting debt, staving off sour memories of relationships past or coming to terms with her own vocal limitations, I wished she could have reckoned more fully with an apparent, and deep-seated, lack of self-esteem. (For example, in the acknowledgments section, Horn says that without the help of key allies, the book would have been “a few pages about singing and the rest about what a loser I am.”)

Hold up your accomplishments and be proud, I wanted to shout, then I thought better. For all of us, at any age, get stuck or sidetracked by what life brings, and behavioral patterns won’t go away just because we want them to.

Singing, however, can chase away the blues, “similar to falling in love for the first time” as Horn describes. The bones of “Imperfect Harmony” may have some loose narrative and emotional joints, and at times the book resembles the slow panic of a performance where “the timing was just enough off-kilter that all the vocal parts had started to veer away from each other.” But just as Horn’s conductor remains unflappable and rights the ship, so, too, does Horn create a paean to the joys of communal singing that’s both familiar and thrillingly new, and worthy of the closing standing ovation.

Sarah Weinman is the editor of “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense,” coming August 27 from Penguin.