Rescued Auschwitz Opera ‘The Passenger’ Gets Long-Awaited Premiere in Houston

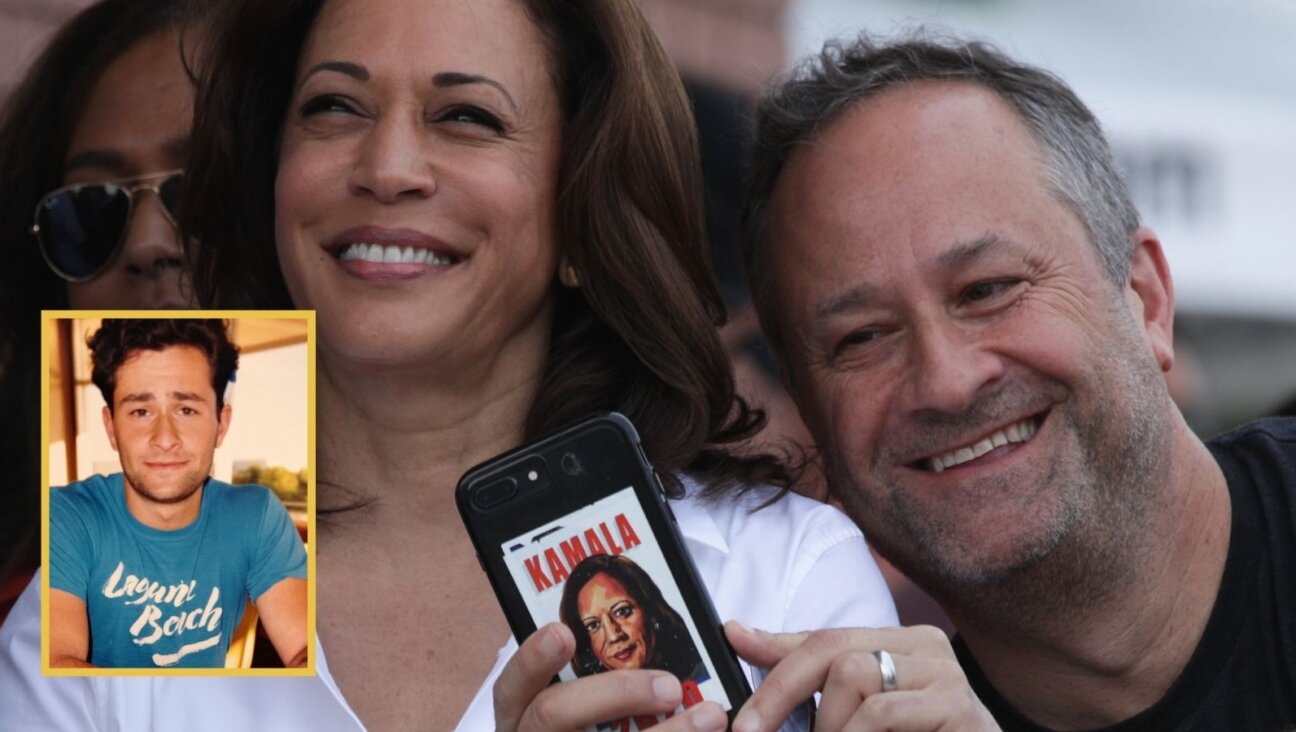

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

For nearly half a century, “The Passenger,” a gripping opera set in Auschwitz, lay dormant. Commissioned by the Bolshoi Theatre in the former Soviet Union, it was supposed to receive its premiere in 1968, but that never happened.

“Soviet authorities didn’t think a piece about Jews would further the interests of the communist state,” said David Pountney, the acclaimed British director who rediscovered the work. “‘The Passenger’ was, for all practical purposes, banned there.”

Now, on January 18, at Texas’s Houston Grand Opera, the opera, considered to be the masterwork of composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg, will finally receive its American premiere.

“The Passenger” takes place in the 1950s on a cruise ship, where one woman — a former SS guard at Auschwitz who has hidden her past from her new husband — is certain that she recognizes a prisoner she thought had perished at the camp. The story alternates between the present-day drama of conscience and flashbacks to the guard and prisoner’s complex relationship at Auschwitz. A two-level set (ship on top, camp on bottom) emphasizes the interconnectedness of these two otherwise disparate settings.

“These women were both 19, and they should’ve met in a university canteen and had a row about a boyfriend,” Pountney said. “The difference is that this university was Auschwitz. It is an extraordinary relationship that the opera explores in an intelligent, sensitive way.”

The opera — which was not performed until 2010 — has a story that seems almost as compelling as any theatrical plot. Weinberg “was himself a passenger of the 20th century,” said Pountney, who directed the opera’s 2010 premiere in Austria and is bringing it to Houston. This summer, the week of July 10, it will have three performances as part of the Lincoln Center Festival.

Weinberg was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1919. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Weinberg, then a 19-year-old music student, fled Poland for the Soviet Union on foot. The only member of his family to survive the Holocaust, Weinberg landed briefly in Minsk and then, with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, was evacuated, along with other artists, to Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

In Tashkent, Weinberg met and married the daughter of Solomon Mikhoels, a famous Soviet Jewish actor and the director of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater. His close friend Marc Chagall painted murals for the theater’s interior. With the help of Mikhoels’s and Weinberg’s new booster, Dmitri Shostakovich, Weinberg and his wife moved to Moscow in 1943. But when his father in-law was assassinated on Stalin’s orders in 1948, Weinberg’s position in the Soviet Union became more tenuous. He was imprisoned briefly in 1953, and though he continued writing music, he received no support from the state.

Weinberg hoped to live long enough to see “The Passenger” performed, but he died in 1996, almost 15 years before the world premiere at Austria’s Bregenz Festival. Pountney had been investigating Weinberg’s work for years by this point. “Since the ’70s, I’d been asking: Who came after Shostakovich and Prokofiev? But of course it was very difficult to get information out of the Soviet Union.” Bit by bit he started hearing about Weinberg, and eventually he got a hold of several recordings of “The Passenger.” “As I began to listen to it,” he said, “I realized that Weinberg was a really serious composer.”

Weinberg adapted the story from a Polish radio play and novel by Zofia Posmysz, who spent three years as a prisoner in Auschwitz. More than a decade after surviving the camps, Posmysz — who is now 90 — was strolling through the Place de la Concorde when she thought she overheard the German voice of a former camp guard. It was this experience that inspired “The Passenger,” which is told from the guard’s point of view instead of the prisoner’s.

Pountney acknowledges the inherent difficulty of pulling off an opera on such a subject. “I’m a little equivocal about all these novels and plays coming out now about Auschwitz that really crank up the emotional temperature,” he said. But despite the lush, heavily orchestrated music, Weinberg and his librettist, Alexander Medvedev, avoided the usual pitfalls.

“It’s a very, very good opera, even if you’re not particularly moved by the subject of Auschwitz,” Pountney said. “Of course, one can’t ignore that Auschwitz carries a unique weight and emotional impact. Weinberg could still have gotten it wrong if there had been any sense of overemotional operatic grandstanding. The subtlety and restraint with which he handles the subject is just extraordinary.”

After its premiere in Bregenz, “The Passenger” was produced in Warsaw and London. The Houston performances run through February 2.

Since opera schedules are “between five and 10 years in the planning,” according to HGO’s managing director, Perryn Leech, HGO has had ample opportunity to organize local cultural and educational events surrounding the premiere. Through partnerships with the Holocaust Museum Houston and the Jewish Community Center of Houston, it has been presenting numerous “Passenger”-related events, such as lectures, salons and a screening of the unfinished 1963 Polish movie based on the same story.

“We want to educate the next generation of people whilst we still have Holocaust survivors among us,” Leech said, “and this great piece of art tells the story wonderfully. There aren’t many operas that allow you to open up conversations and have educational events.”

Laura Moser may be reached at [email protected]