Genetics Lab Refuses To Share Data That Could Save Lives

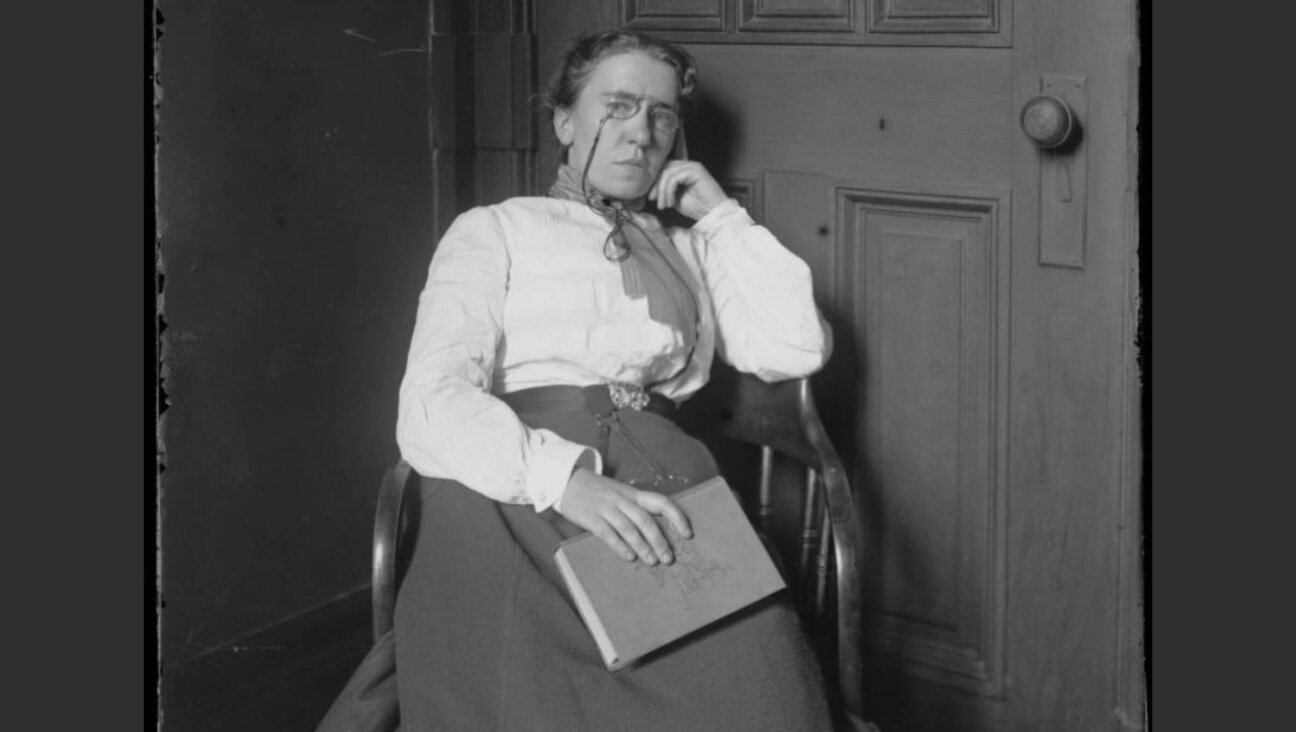

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Myriad Genetics may have lost its singular hold on the market for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in May 2013 when the Supreme Court ruled against the patenting of genes, but few outside the science and medical communities are aware that Myriad continues to possess a repository of patient data from BRCA testing that it does not share with researchers outside its own lab.

After testing for a genetic mutation related to BRCA, some people — around 3 to 7% of cases — receive the result “variant of uncertain significance.” This indicates that the lab found a genetic change that may be linked to cancer risks but was unable to determine whether the gene change is a “deleterious change,” which increases the risk for cancer, or a variant that does not. Until the Supreme Court ruling which allowed other labs to begin conducting BRCA testing, Myriad had been for 16 years the sole commercial provider in the United States collecting those variants, which are important tools for interpreting results. It stopped contributing those results to the public database Breast Information Core, the largest database for BRCA mutations, in 2004.

Together, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for about 20 to 25% of hereditary breast cancers and about 5 to 10% of all breast cancers. Researchers are now studying these less common variants that have emerged in genetic testing to try to understand if they’re inherited and if they cause cancer. To prove cause and effect, large amounts of data are needed — thus, the dire need for the variants Myriad has been collecting.

“This is not the way that most genetics work has taken place and the fact that they have data on these variants that are hard to interpret that they have not shared has generally been really disturbing to the medical community,” said Judy Garber, director of the Center for Cancer Genetics and Prevention at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Myriad said it stopped contributing its data to BIC in 2004 because the database lacked operational and clinical standards, was subject to funding cuts, and could not handle the volume of data Myriad was contributing.

“When the data gets put in the database, there are no standards for who puts it in — the level of expertise required to actually contribute to the database,” said Rick Wenstrup, chief medical officer of Myriad Genetics. Wenstrup contends that BIC was only ever intended to be a research database and was never meant to be used to make clinical classifications. He said the fact that other researchers and laboratories do so places patients at risk.

“The data they are relying on are not curated data,” he said.

As a matter of policy, Wenstrup said Myriad does not use any publically available databases that contain clinical information and clinical classification of specific variants. This includes a newer database called ClinVar, launched in April 2013 by the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

When asked about Myriad’s contention that public databases aren’t clinic-ready, Dr. Erin Ramos, an epidemiologist in the National Human Genome Research Institute, did not comment on the issue but instead appealed to the research community’s greater benefit. “In order to achieve the promise of genomic medicine and to ensure transparency, these findings must be annotated and made available to the research and clinical communities,” she said.

Wenstrup viewed that as a losing proposition for Myriad. “Why would we hand over a database when these public databases have a lot of work to do on quality control to make sure that they are sufficiently clinic ready?” he asked. Wenstrup said Myriad would consider sharing its data if there was a way to do so without competing laboratories being able to harness the information for their own BRCA testing efforts. When asked if he would consider contributing the data for the greater good of patients, Wenstrup reversed the question: “Is it ethically responsible for a lab that has relatively little experience to offer tests to determine cancer because they’ve got a lab director and they’ve bought some equipment?” he asked. “We are a company and our primary ethical and moral responsibilities are to the patients we test.”

Elizabeth Chao, chief medical officer at Ambry Genetics, suggested that Myriad’s argument was a false one — that labs don’t use public databases to the exclusion of other information in interpreting results.

“ClinVar and BIC are critical tools that pool the collective wisdom of thousands of breast cancer researchers over the last two decades,” said Chao. “What is important to remember is that we [Ambry] don’t use these databases as stand-alone clinical tools, nor are they intended to be applied in this way. Our approach is to integrate them into our analysis and get the best of both worlds, providing the most up-to-date interpretation to both doctor and patient in understanding their genetic test result.”

A movement of data sharing is afoot to fill the void of BRCA variant data. Sharing Clinical Reports Project enlists the cooperation of cancer genetics or hereditary cancer clinics around the country to aggregate BRCA testing results reported by Myriad since 2006 into ClinVar.

“Having collected lots of variants from Myriad’s reports, we can already see hundreds of variants classified as VUS,” said Heidi Rehm, head of the Laboratory for Molecular Medicine at the non-profit company Partners HealthCare in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which is part of the initiative. “So clearly, they still have much to learn. They will gain that knowledge by sharing.”

Patient advocate Sue Friedman of Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered, part of the patient data-sharing initiative of ClinVar, expressed concern about whether Myriad was informing those taking their tests that that lab does not share its results with other researchers.

“Were they aware of the fact their data was being used for research and that it would not be shared? Did they sign a consent form?” she asked.

To that Wenstrup replied, “I don’t think this particular issue comes up in the discussion between the clinician and their patient when they are trying to assess cancer risk. I think the conversation is really built around how we can get the most accurate result possible.”

Andrea Downing, an activist for the Free The Data movement, which appeals directly to patients to share their testing results anonymously, puts a face on the statistics. She tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation called C61G at age 25 and had a preventive double mastectomy two years ago. The mutation was passed from her great-grandmother to her grandmother to her mother, who was diagnosed with Stage 3 cancer in her early 30s.

She cites a particular BRCA1 variant, 2269delG, as having only two search results in the ClinVar database. “The only reason this variant was reported is because of the Invitae lab and Sharing Clinical Reports,” said Downing. Were it not for these efforts, information that could save lives would have remained inaccessible.

Karen Iris Tucker is a freelance writer who writes about health, entertainment and cultural politics. Contact her at [email protected]