Was Leo Tolstoy Really an Anti-Semite?

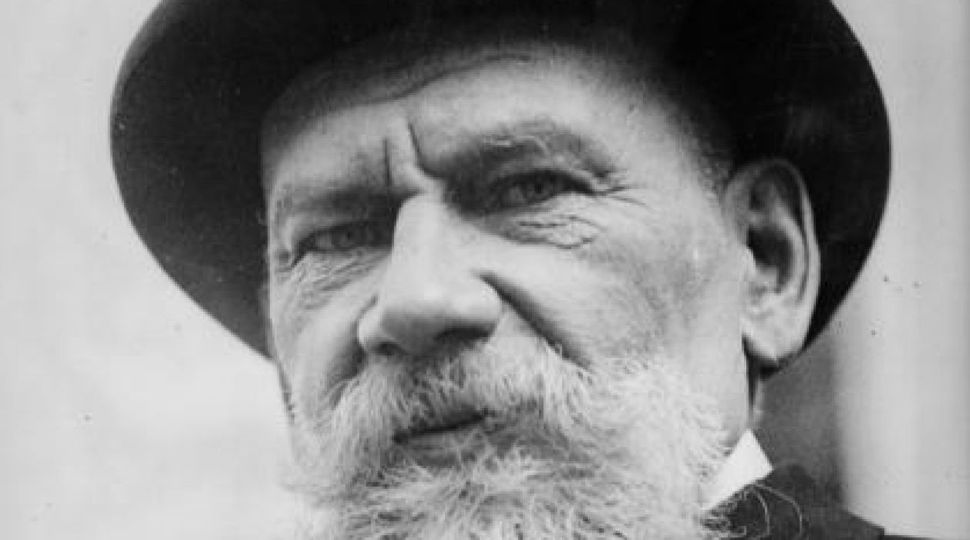

The Count: Leo Tolstoy seemed either unable or unwilling to portray a Jewish character in his fiction. Image by Getty Images

Duelling new English-language versions of the 1870s novel “Anna Karenina” are raising questions about the novelist Leo Tolstoy’s complex and contradictory attitudes toward Jews. Placed by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin in his famous essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox” among the foxes (who know many things) as opposed to the hedgehog (who knows one big thing), Tolstoy proves his multiplicity even when it comes to writing about Jews in “Anna Karenina.”

Although puns are reputed to be untranslatable, Rosamund Bartlett and Marian Schwartz tackle the challenge, competing with the decade-old version by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, recently reissued by Penguin Classics..

The silly, self-indulgent character Stiva Oblonsky, a well-born Moscow civil servant, makes a lame pun when he announces that he spent two hours waiting to see a Jewish man: “I had business with a Jew, and I waited.” (“Bylo delo do zhida I ya do zhida-lsya.”) The pun rests on the same sound in Russian for the words “with a Jew” and “waited.” The century-old Aylmer Maude translation tries to replicate this effect with “I had business with a Jew, but could not get at him even to say ajew (adieu).” Pevear and Volokhonsky replace this with “I had much a-jew with a Jew.” Sydney Schultze, in “The Structure of Anna Karenina” suggests: “I had business with a Jew, and I jewst had to wait.”

The most offensive alternative is from the new translation by Bartlett, which has Oblonsky “thinking up a pun about having wait-yid to see a yid.” Introducing and repeating a pejorative in English that was only implicit in the original, Bartlett claims in a note that the “practice of referring to a Jew as a ‘Yid’ was widespread in nineteenth century Russia, and not perceived as necessarily pejorative.”

The 1982 article “‘Zhid’: Biography of a Russian Epithet” by John D. Klier, a historian of Russian Jewry, does not concur. Klier explains that by the mid-19th century, decades before “Anna Karenina” was published, the “gradual transformation of the term into one of opprobrium” had already occurred, changing “zhid from a description into an insult.”

More essentially, Tolstoy was unable or unwilling to portray a significant Jewish character in his fiction. In his “History of Anti-Semitism,” the French Jewish historian Léon Poliakov laments: “It seems that Tolstoy the artist… was not able to identify with a Jew.”

Exploring this paradox, “Tolstoi and the Jews,” a landmark 1982 article by Harold Schefski,, points out how Tolstoy was a walking contradiction in terms, obsessed with pacifism and conflict, self-indulgence and self-denial, the aristocratic lifestyle and peasant virtues. Accordingly, his feelings about the Jews seemed to vary year by year. Schefski warns against monolithic conclusions such as those of the Ukrainian Jewish scholar L. G. Barats, whose short work, 1961’s “Tolstoi and the Jews,” states: “For the Jew alone, Tolstoy could not find a place in his expansive and loving heart.”

Following a celebrated existential crisis after writing “Anna Karenina,” Tolstoy became obsessed by religion and began to circulate maxims such as “We all die alone and in agony,” and titled a story ominously, “God sees the truth, but waits.” His “Examination of the Gospels” asserts that Christianity did not follow Judaism, but is instead its opposite: “Moses gave us the old law ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth’ and Christ repealed this law with his own law ‘Resist not evil, or him that is evil.’” In his “What I Believe,” Tolstoy dismissed Mosaic law for being replete with “such minute, meaningless and often cruel rules,” as opposed to Christianity, which to him was all about love. In “The Gospel in Brief,” Tolstoy even dismissed the Jewish celebration of Shabbat, declaring: “And now Jesus says that this Sabbath is a petty detail and an invention of man.”

Yet by 1891, as Schefski notes, when he published “What Is a Jew?” Tolstoy had changed his mind. He announces: “The Jew is that sacred being who has brought down from heaven the everlasting fire and has illumined with it the entire world… The Jew is the religious source, spring and fountain out of which all the rest of the peoples have drawn their beliefs and their religions.”

The year before, in a letter to the Jewish journalist Faivl Getz, Tolstoy ranked Jewish law above Christian law, at least as it was then observed in Russia: “The moral teaching of the Jews and the practical example of their lives stand incomparably higher than the moral teaching and the practical example set by the people of our quasi-Christian society… Judaism, by adhering to the moral principles which it professes, occupies a higher position than quasi-Christianity in everything that comprises the goals of our society’s aspirations.”

By January 1906, Tolstoy had again reversed himself, complaining in his diary that the “Jewish faith is most irreligious… It is a proud faith in that Jews consider only themselves as the chosen people of God.” He remained silent about the Dreyfus Affair which split Europe because, Schefski notes, the French officer Alfred Dreyfus as a “member of the privileged class, was not worthy of sympathy” compared to thousands of unjustly imprisoned, defenseless Russian Jews. Yet after the bloody Kishinev pogrom in April 1903, Tolstoy did sign a letter of protest in the spirit of non-violence, and contributed writings to an anthology that Sholem Aleichem organized in memory of pogrom victims.

Perhaps because of such actions, Tolstoy attracted a number of Jewish disciples, including the pianist Alexander Goldenweiser and composer Isaak Feinerman. The latter, a Ukrainian Jew, was so strongly influenced by Tolstoy’s ideas that he gave all his possessions to the poor, leaving his wife and child destitute, much to the dismay of Tolstoy’s wife Sophia, who jotted in her diary: “However fanatical his beliefs may be, and however beautifully he may express them, the fact is that he has left his family to eat at others’ expense, and that is grotesque.” In 1882, Tolstoy reported to a friend that he was studying Hebrew with a “very good and intelligent person,” the rabbi Solomon Minor. Yet upon hearing that his friend Goldenweiser had fainted after running up a hill, he wisecracked, “All this happened because everywhere Jews always strive to be first.”

Regardless, Jewish devotees worshiped Tolstoy, including the Russian-born British translator Samuel Solomonovich Koteliansky. As described in Galya Diment’s “A Russian Jew of Bloomsbury,” Koteliansky collaborated with Leonard and Virginia Woolf on translations of A.B. Goldenweizer’s “Talks with Tolstoi”; Maxim Gorky’s memoir about Tolstoy; and the “Autobiography of Countess Tolstoy.”

More recently, in 2012, the Holocaust survivor Mira Crouch published an essay, “Reading Anna Karenina, Considering the Holocaust,” relating her family’s escape from fascist Europe in 1939 to the humanist ideals of Tolstoy who opposed political persecution. On the thorny subject of Tolstoy and the Jews, positive things have long outweighed the negatives, at least for many interested observers.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.