Abraham Lincoln’s greatest gift to the Jews

The roots of Abraham Lincoln’s Judeophilia can be traced back to his childhood in Indiana

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Editor’s note: We have republished this story, originally published in 2015, for Presidents Day.

“In central Jerusalem, close by streets named for the medieval Jewish luminary Moses Maimonides and the modern Hebrew writer Peretz Smolenskin, and abutting the American consulate, lies a crooked street named for Abraham Lincoln. When questioned about what he did for the Jewish people to merit a street named for him in Jerusalem, even those Jerusalemites familiar with Lincoln’s biography shake their heads and shrug.” So writes Jonathan D. Sarna in the introduction of his latest book, “Lincoln and the Jews: A History,” which he coauthored with Benjamin Shapell.

Those Israelis are not the only ones; even someone as knowledgeable as Sarna, the Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis, was surprised to discover how much he had to learn about Lincoln’s relationship with Jews, as he and Shapell, who founded the Shapell Manuscript Foundation, an educational non-profit, prepared their book for publication this March. Notwithstanding all that had been written before about Lincoln, Sarna said they found a lot of new material. Their research also served as basis for an exhibition on the same topic, which opens at the New-York Historical Society this month and will travel to other locations across the country.

“Nobody realized that Lincoln played such a crucial role in making Jews equal in America. Nobody paid attention to Lincoln’s rhetorical shift away from ‘Christian America’ language, and toward inclusive language,” Sarna states. In their comprehensive and readable narrative history, Sarna and Shappell try to remedy that ignorance among both Jewish and non-Jewish readers. “We make the case that this is a highly important aspect of Lincoln’s life and legacy — that he, unlike many others at the time, viewed Jews as equals and befriended them,” Sarna said in an interview with the Forward.

The roots of Abraham Lincoln’s Judeophilia can be traced back to his childhood in Indiana. His parents, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, were Protestants who belonged to a church that opposed the conversion of Jews. That’s because they believed that missionaries were assuming responsibilities for the fate of others that properly belonged to God alone.

Lincoln’s Jewish BFF: Abraham Jonas prevented a conspiracy. Image by Wells Family Collection

The future president first had actual contact with Jews when he moved to Springfield, Illinois in 1837, where he encountered Jewish neighbors, clients and political allies. Abraham Jonas, who, like Lincoln, was an attorney and state legislator, became the only person Lincoln is known to have dubbed “one of my most trusted friends.” Jonas’s support at a crucial moment may well have changed the course of history: In 1858, Lincoln lost the election for U.S. Senate. When Henry Asbury, Jonas’s law partner, suggested that Lincoln be considered for the 1860 Republican presidential nomination in a meeting with Horace Greeley, the New-York Tribune editor, this idea was not warmly received — until Jonas reinforced Asbury’s proposal. Jonas next worked strenuously to increase support for the Republican Party, and to secure the nomination for his friend at the party’s convention in Chicago. Before Lincoln took office, Jonas received word from a relative of a conspiracy to prevent his inauguration, possibly with violent means, and urged his friend to take precautions. His warnings were taken seriously: Lincoln was smuggled into Washington at night.

Once Lincoln was in the White House, he displayed his empathy and tolerance for Jews on numerous occasions. The Fifth Pennsylvania Cavalry had a Jewish commander and over 30 Jewish members, and, in 1861, elected Michael M. Allen, a Jewish liquor dealer, as the regimental chaplain. The unit was unaware that Congress had just established a requirement that military chaplains must be ministers of “a Christian denomination.” Once Allen learned his election violated that standard, he resigned. But the Fifth Pennsylvania was not daunted by this setback. The regiment promptly elected Arnold Fischel, a teacher and lecturer from New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, as their chaplain — only to have the choice nixed by the secretary of war.

This congressional declaration that amounted to second-class status for Jews became a rallying point for American Jewry. Fischel showed up at the White House on December 11, 1861, even though he had been told that Lincoln was too busy to meet. Amazingly, he was invited to speak with Lincoln. The president agreed that the legislation was unjust, and crafted a compromise that allowed Jews to minister to their coreligionists in the army.

Lincoln again displayed his sensitivity and sense of justice about a year later, when General Ulysses S. Grant issued the infamous General Orders No. 11, dubbed by Sarna and Shapell as “the most notorious official act of anti-Semitism in American history.” Grant’s concern about smugglers in the areas under his command led to the order, after he decided that since some of the smugglers were Jewish, all were. His decree expelled all Jews from the Department [of the Tennessee] within 24 hours from the receipt of the order.

“Lincoln could have easily turned away,” said Harold Holzer, the chief historian of the New-York Historical Society exhibit, in an interview with the Forward. American Jews numbered only a small percentage of the population, and were in no way a significant political lobby at the time. Lincoln took a considerable risk in telling Grant’s commander to rescind General Orders No. 11: He did not want to alienate Grant, as he needed his military skills to win the Civil War, and viewed the general as a potential political rival for the 1864 presidential election. Notwithstanding those concerns, Lincoln viewed the expulsion order as unjust, and overturned it. “I do not like to hear a class or nationality condemned on account of a few sinners,” Lincoln told a Jewish delegation that had come to thank him in January 1865. (Somewhat ironically, Grant went on to appoint a record number of Jews to office, and to become the first president known to have attended synagogue services — Kabbalat Shabbat at an Orthodox congregation in Washington, D.C.)

For Shapell, Lincoln’s handling of General Orders No. 11 exemplifies what was special about him. “It shows us how different Lincoln was, how alone he was in standing for freedom and justice — while, at the same time, his revered general is punishing one group based on religion, Lincoln is freeing a race,” he said, referring to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

As the 1864 presidential election neared, Lincoln worried about his prospects. One of the people he turned to for help was another Jewish friend, Issachar Zacharie, his foot doctor. Lincoln was concerned enough about his electoral support that he met with Jewish leaders to discuss the Jewish vote, and Zacharie labored in private to turn out Jewish voters for the president. Records do not indicate what percentage actually did so.

Lincoln’s interest in things Jewish was not only expressed in his responses to discrimination or political challenges. As Sarna and Shapell note, he also admired Jewish theater. He saw “Gamea, or the Jewish Mother,” a play by creole writer Victor Séjour that was inspired by the abduction of Edgardo Mortara by the papal police in 1858, twice. The couple also watched a performance of “Leah, the Forsaken,” a play by Augustin Daly about the persecution of Jews in 18th-century Austria. As did Séjour’s, the play spoke to the evils of persecuting a minority and showed how Jews and African Americans faced similar biases at the time.

According to a letter by Mary Todd Lincoln, who frequently invited Jews to parties at the White House at a time when that would have been considered unthinkable to many, Lincoln said on the last day of his life that he planned to visit Palestine after his second term in office ended.

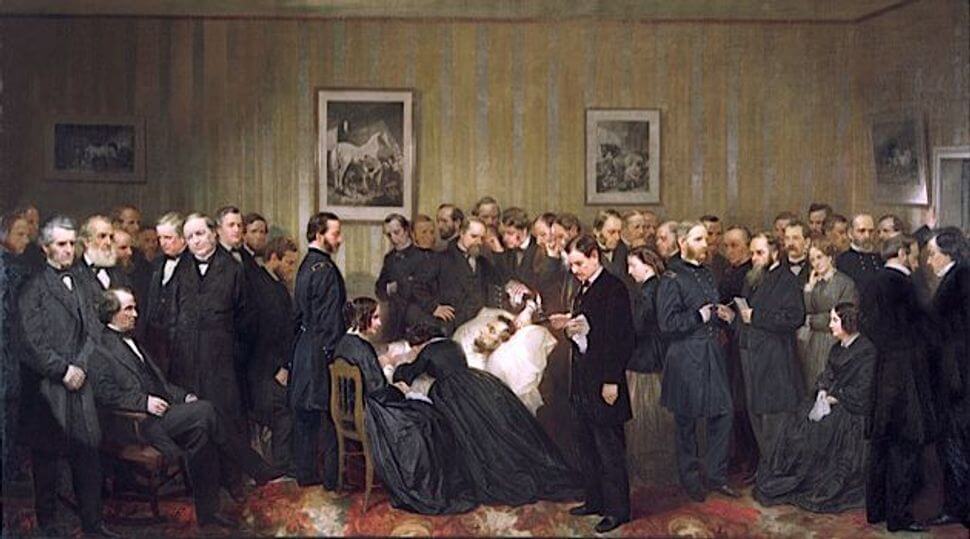

Lincoln’s murder on April 14, 1865, which was both Good Friday and the evening of the fifth day of Passover, was devastating for much of American Jewry. The responses to his death in the Jewish community demonstrated the unique regard in which he was held. Holzer believes that Lincoln was the first non-Jew for whom Kaddish was said. Many Jewish eulogies compared his wish to visit Jerusalem with Moses, who died before seeing Israel.

After his passing, Lincoln was virtually transformed into the first Jewish president, a process vividly described by Gary Phillip Zola, a historian and rabbi, in his recent major study on Lincoln’s place in American Jewish memory. His book, “We Called Him Rabbi Abraham,” nicely complements “Lincoln and the Jews.” Zola focuses on how the American Jewish community embraced Lincoln, “as if he was one of our own.” That embrace crossed denominational lines: Major movement leaders such as Solomon Schechter, who compared Lincoln to Hillel (“We may well be grateful to God for giving us such a great soul as Lincoln”), and Bernard Revel (“In Lincoln himself were fused all the essential elements of Judaism”) praised the president in ceremonies marking the centennial of his birth in 1909.

This connection is still strong today, writes Zola: “[F]rom the moment Lincoln was assassinated, American Jews regarded the martyred president as a national icon who, though not a Jew by birth, was genuinely imbued with Jewish values and had a ‘Jewish soul.’”

Lenny Picker is an attorney in New York City.