A Tale of Two Trains

I am on a train heading into Magdeburg in eastern Germany, an hour or so from Berlin. Sixty-one years ago, my late mother was on a train headed for Magdeburg. Hers didn’t have a dining car or changing electronic displays updating the train’s speed and distance from its next station. She was one of hundreds of internees being transported from the concentration camp of Stutthof in sealed and stinking cattle cars.

In Magdeburg, she would be a slave laborer at Polte Fabrik, Germany’s largest munitions plant. The factory was the scene of many accidents, and every night she would dream of her fingers being cut off. These dreams haunted her many years after her liberation.

They haunt me, as I look down at my hands. I’m coming to do a very different kind of work. I’m on a two-week book tour, scheduled to speak about and read from my novel, “The German Money” (Leapfrog Press), the story of a Holocaust survivor’s adult children who are arguing about their mother’s will.

As the train nears the station, it hits me that this entrance could not be more American. My mother was a slave; she survived, immigrated to the United States and bore me in the world’s freest country. Me, I’m returning to the scene of her imprisonment as a successful American author with two more books scheduled to be published in Germany.

Germany, the country I swore never to visit. The country whose products I never bought, the country that was so alien and radioactive that when I was a child, I used to imagine maps of Europe without it — as if I were a superhero whose laser gaze could slice it away from the continent and sink it without a trace. Then Switzerland would have a seacoast. Austria, too.

And I would have revenge for the camps and killing squads that not only murdered dozens of my parents’ relatives but also poisoned their memories. Talking about their lost parents, cousins, aunts and uncles was so painful for my own parents that I have no family tree to climb in middle age, no names and professions and cities to study and explore. The Nazis certainly won that round — like a giant grinding his victim’s bones to dust.

Growing up in New York, I bristled on buses and in the subway if I heard someone old enough to have been a camp guard or Nazi soldier speaking German. Were you there? I wondered. Yet here I am, going over an introduction that a German-speaking friend helped me write. It seems only polite to break the ice with my audiences that way, and I am enjoying people’s reaction: surprise that an American would even attempt to speak German, and enjoyment that I have done so correctly.

The bookstore, connected to the Protestant cathedral a block away, is packed before I begin, with at least 40 people looking interested and attentive. It’s warm, and at times I feel compelled to do better than I’ve ever done before, because not so far away, my mother was an utterly expendable cog in the German war machine. My book is a challenge to that. The questions come slowly. And while I understand some of the German, at times a fog of incomprehension sweeps over me and I have to wait for the translation. How long did the book take to write? How much is autobiographical? Can I say more about my mother’s experiences in Magdeburg? How much did my parents talk about their war years?

And then, this: Is forgiveness possible?

I start with my mother, who told me she never blamed all Germans, and younger Germans surely had nothing to do with events before their birth. She even once responded positively when a friend in graduate school raised the possibility of spending a summer abroad at a German university.

But that was her. What do I think?

“Forgiveness?” I ask. “Of course it’s possible. If not, I wouldn’t be here.” When the long evening ends with applause and some announcements, the effusive bookstore owner gifts me with a book about Magdeburg and with two bottles of local liqueurs.

Humbled, all I can think of is the end of William Faulkner’s “Light in August”: “My, my. A body does get around.”

Lev Raphael’s “Writing a Jewish Life” (Carroll & Graf) and “Secret Anniversaries of the Heart” (Leapfrog) are due this winter.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Should Diaspora Jews be buried in Israel? A rabbi responds

-

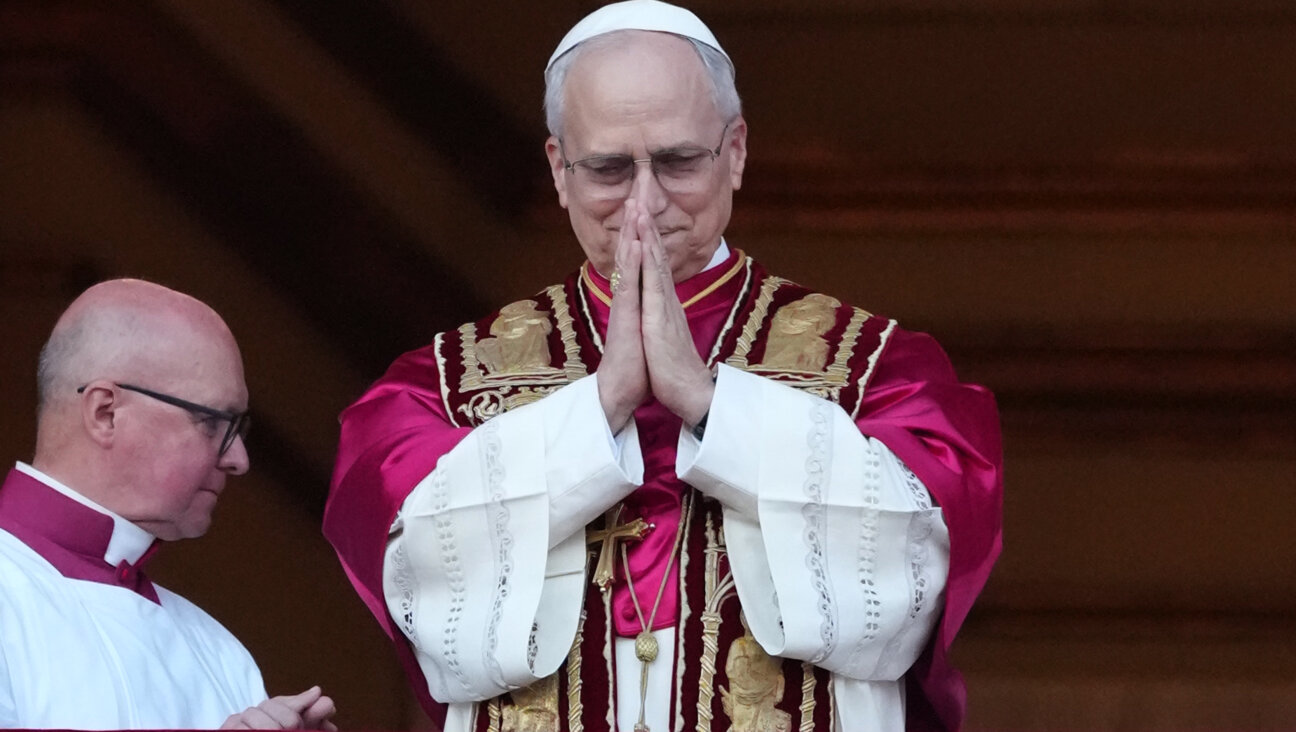

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.